Commercial hi-res Earth imaging satellite constellations limiting Gaza imagery to the public

Once Israel’s ground campaign into Gaza started the new American private commercial hi-res Earth imaging satellite constellation companies began restricting access to their imagery.

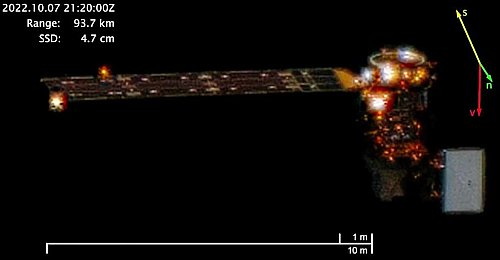

Planet, a San Francisco-based company launched in 2010 by former NASA scientists, has in recent days heavily restricted and obscured parts of images over the Gaza Strip for many users, including news organizations. Last week, some images of Gaza were removed from Planet’s web application for downloading imagery, and some have been distributed to interested media outlets through a Google Drive folder. The satellite company told some subscribers that during active conflicts, it may modify pictures published to the archive.

…Some commercial satellite companies appear to be releasing their detailed images — but with a time delay. Planet and a competitor, Maxar Technologies, have released images shared with the New York Times, Washington Post, and other news outlets on a significant time delay. Starting on Nov. 3, both papers shared exclusive images taken by Planet on Nov. 1. Airbus, another major commercial satellite image provider, has not shared images of Gaza.

It appears the companies have done so for two reasons: First, it appears these companies have actually decided they do not wish to reveal any information that might hurt Israel’s ground campaign. This approach differs significantly from the leftist mainstream American press, which either doesn’t care what harm it does, or is eager to sabotage Israel’s effort.

Second, it appears the companies have been reminded of a 1997 federal law, called the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment, that forbids the release of “imagery of Israel that’s at a higher resolution than what’s distributed by non-US companies.”

Once Israel’s ground campaign into Gaza started the new American private commercial hi-res Earth imaging satellite constellation companies began restricting access to their imagery.

Planet, a San Francisco-based company launched in 2010 by former NASA scientists, has in recent days heavily restricted and obscured parts of images over the Gaza Strip for many users, including news organizations. Last week, some images of Gaza were removed from Planet’s web application for downloading imagery, and some have been distributed to interested media outlets through a Google Drive folder. The satellite company told some subscribers that during active conflicts, it may modify pictures published to the archive.

…Some commercial satellite companies appear to be releasing their detailed images — but with a time delay. Planet and a competitor, Maxar Technologies, have released images shared with the New York Times, Washington Post, and other news outlets on a significant time delay. Starting on Nov. 3, both papers shared exclusive images taken by Planet on Nov. 1. Airbus, another major commercial satellite image provider, has not shared images of Gaza.

It appears the companies have done so for two reasons: First, it appears these companies have actually decided they do not wish to reveal any information that might hurt Israel’s ground campaign. This approach differs significantly from the leftist mainstream American press, which either doesn’t care what harm it does, or is eager to sabotage Israel’s effort.

Second, it appears the companies have been reminded of a 1997 federal law, called the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment, that forbids the release of “imagery of Israel that’s at a higher resolution than what’s distributed by non-US companies.”