Scientists think methane detections by Curiosity come from the salts in the local soil

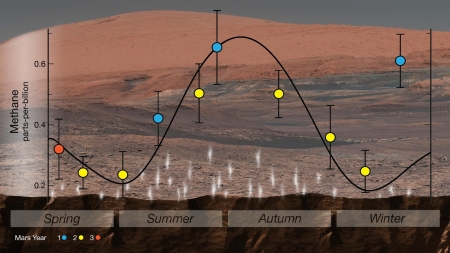

According to experiments conducted on Earth, some scientists believe the unexpected puffs of methane detected by Curiosity periodically come from the salts in the local soil.

Led by Alexander Pavlov, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, the researchers suggest the gas also can erupt in puffs when seals crack under the pressure of, say, a rover the size of a small SUV driving over it. The team’s hypothesis may help explain why methane is detected only in Gale Crater, Pavlov said, given that’s it’s one of two places on Mars where a robot is roving and drilling the surface. (The other is Jezero Crater, where NASA’s Perseverance rover is working, though that rover doesn’t have a methane-detecting instrument.)

The theory, based on those experiments, is complicated and unconfirmed, but if so it suggests that much of the soil of Mars, its regolith, will be somewhat toxic, requiring some processing to make it possible for plants to grow in it. This is not a new discovery, but confirms past data that suggested that perchlorate — a mild acid — is found everywhere on Mars.

According to experiments conducted on Earth, some scientists believe the unexpected puffs of methane detected by Curiosity periodically come from the salts in the local soil.

Led by Alexander Pavlov, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, the researchers suggest the gas also can erupt in puffs when seals crack under the pressure of, say, a rover the size of a small SUV driving over it. The team’s hypothesis may help explain why methane is detected only in Gale Crater, Pavlov said, given that’s it’s one of two places on Mars where a robot is roving and drilling the surface. (The other is Jezero Crater, where NASA’s Perseverance rover is working, though that rover doesn’t have a methane-detecting instrument.)

The theory, based on those experiments, is complicated and unconfirmed, but if so it suggests that much of the soil of Mars, its regolith, will be somewhat toxic, requiring some processing to make it possible for plants to grow in it. This is not a new discovery, but confirms past data that suggested that perchlorate — a mild acid — is found everywhere on Mars.