Solar Orbiter takes closest image of Sun so far

Click for full interactive image, where you can zoom in, a lot.

Cool image time! The European Space Agency (ESA) yesterday released several new images from its Solar Orbiter probe, taken when the spacecraft made its most recent closest approach of the Sun.

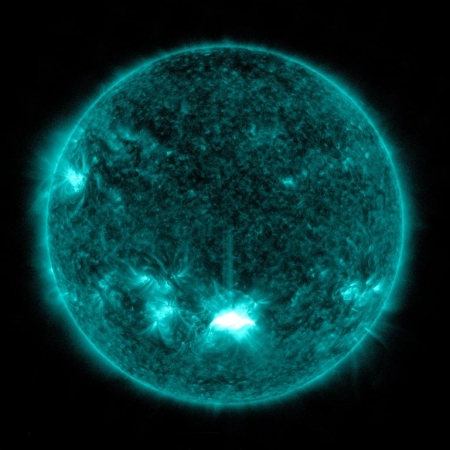

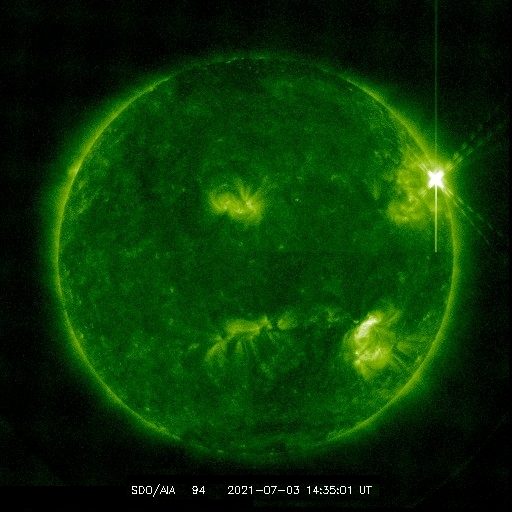

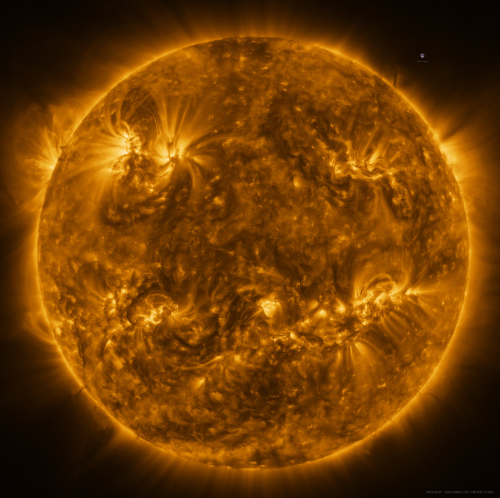

One of the images, taken by the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) is the highest resolution image of the Sun’s full disc and outer atmosphere, the corona, ever taken.

Another image, taken by the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument represents the first full Sun image of its kind in 50 years, and by far the best one, taken at the Lyman-beta wavelength of ultraviolet light that is emitted by hydrogen gas.

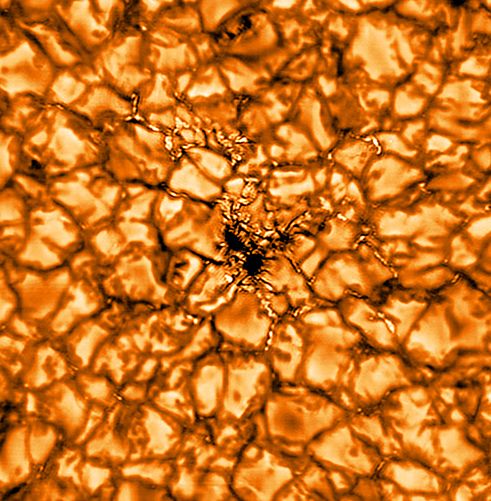

The images were taken when Solar Orbiter was at a distance of roughly 75 million kilometres, half way between our world and its parent star. The high-resolution telescope of EUI takes pictures of such high spatial resolution that, at that close distance, a mosaic of 25 individual images is needed to cover the entire Sun. Taken one after the other, the full image was captured over a period of more than four hours because each tile takes about 10 minutes, including the time for the spacecraft to point from one segment to the next.

The photo to the right, reduced to post here, is the EUI photo.

Solar Orbiter has been in its science orbit since November, though that orbit over time will slowly be adjusted to swing the spacecraft into a higher inclination so that it can make the first close-up observations of the Sun’s polar regions. It is also working in tandem with the Parker Solar Probe, which observes the Sun from even closer distances using different instruments.

Click for full interactive image, where you can zoom in, a lot.

Cool image time! The European Space Agency (ESA) yesterday released several new images from its Solar Orbiter probe, taken when the spacecraft made its most recent closest approach of the Sun.

One of the images, taken by the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) is the highest resolution image of the Sun’s full disc and outer atmosphere, the corona, ever taken.

Another image, taken by the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument represents the first full Sun image of its kind in 50 years, and by far the best one, taken at the Lyman-beta wavelength of ultraviolet light that is emitted by hydrogen gas.

The images were taken when Solar Orbiter was at a distance of roughly 75 million kilometres, half way between our world and its parent star. The high-resolution telescope of EUI takes pictures of such high spatial resolution that, at that close distance, a mosaic of 25 individual images is needed to cover the entire Sun. Taken one after the other, the full image was captured over a period of more than four hours because each tile takes about 10 minutes, including the time for the spacecraft to point from one segment to the next.

The photo to the right, reduced to post here, is the EUI photo.

Solar Orbiter has been in its science orbit since November, though that orbit over time will slowly be adjusted to swing the spacecraft into a higher inclination so that it can make the first close-up observations of the Sun’s polar regions. It is also working in tandem with the Parker Solar Probe, which observes the Sun from even closer distances using different instruments.