Why Martian mountains are different than on Earth

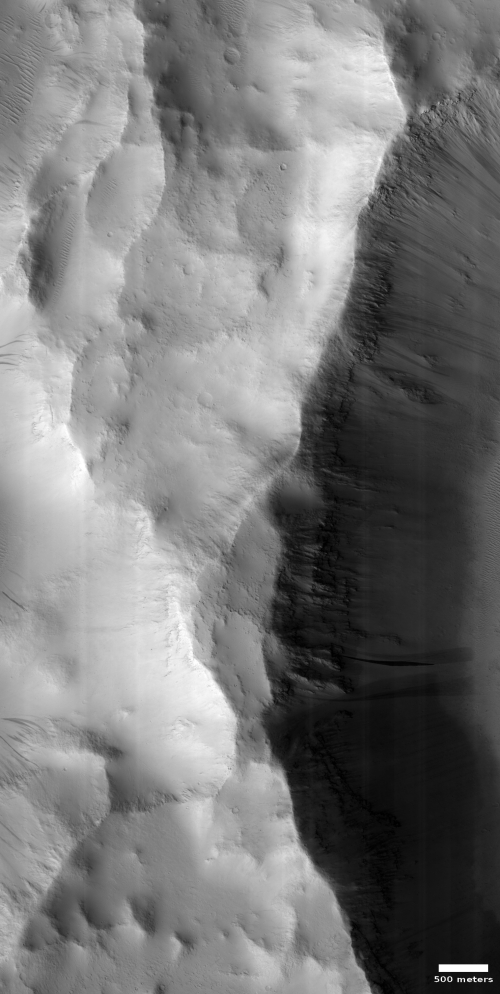

Cool image time! The photo to the right, rotated, cropped, and reduced to post here, was taken on August 12, 2020 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). It shows what to any Earthling’s eye appears to be a somewhat ordinary flat-topped mountain peak with two major flanking ridgelines descending downward to the north and the south, and two minor ridgelines descending to the northwest and southwest.

This peak and its landscape would surely be quite a spectacularly place to visit, should humans ever settle Mars and begin doing sightseeing hikes across its more interesting terrain. I can definitely imagine hiking trails coming up the two minor ridges, with a crest trail traversing the main north-south ridge across the peak.

This is not however a mountain on Earth. It is on Mars, which makes its formation and evolution over time fundamentally different than anything we find on Earth, despite its familiar look.

First, what formed it? Unlike most of Earth’s major mountain chains, the mountains of Mars were not formed by the collision of tectonic plates, squeezing the crust upward. Mars does not have plate tectonics. Most of its mountains formed either from the rise of volcanoes at single hot spots, or from the wearing away of the surrounding terrain to leave behind a peak or mesa.

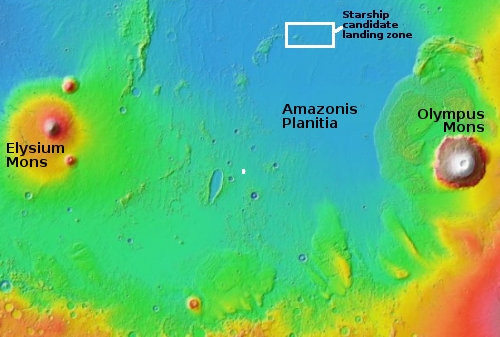

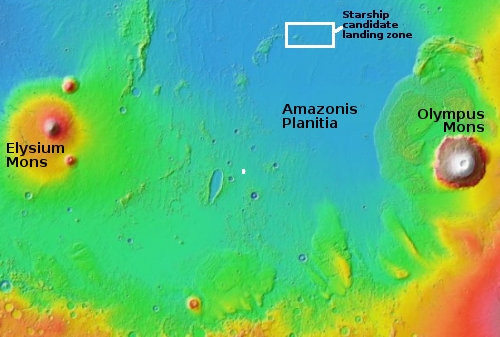

This mountain however was formed from neither of these Martian processes, as the wide overview map to the right illustrates. The peak’s location is indicated by the white rectangle in the center of the image, on the southern border of the vast northern lowland plain dubbed Amazonis Planitia. While giant volcanoes flank it many hundreds of miles away, this peak is in an area with relatively few large mountains. It is also at latitude 17 degrees north, too close to the equator for glacial erosion.

In fact, the peak’s seemingly isolated location makes me think of the Lonely Mountain in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

What caused it if not volcanism or erosion? The answer becomes obvious if we zoom in to look at an overview map from much closer range.

That’s right, this peak forms the high point on the rim of two intersecting impact craters, whose total width is approximately 20 miles across.

Such peaks do not exist on Earth. Almost all of our planet’s craters have long since been erased by both erosion from wind and water and by those tectonic processes that do not exist on Mars. Thus, we have no mountains formed from the instantaneous impacts of two adjacent craters.

And instantaneous it likely was. While it is certainly possible for these two impacts to have occurred separately, at widely spaced times, it is more likely they came from the same large bolide that split as it roared downward through the Martian atmosphere, hitting the ground mere seconds apart. This Martian mountain will thus contain a lot of material ejected from below, with much of it reshaped quickly, from the gigantic heat and pressure created by those impacts.

Mountains on Earth do not form in seconds. The fastest forming are volcanoes, and while they might grow fast, they do not form in mere seconds.

And yet, that is how fast many mountains on Mars formed. Many thousands of craters still exist on Mars, and their mountainous rims are all like this one, formed instantly in time, despite the size of those peaks. It will a geologist’s dream to explore them.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

Cool image time! The photo to the right, rotated, cropped, and reduced to post here, was taken on August 12, 2020 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). It shows what to any Earthling’s eye appears to be a somewhat ordinary flat-topped mountain peak with two major flanking ridgelines descending downward to the north and the south, and two minor ridgelines descending to the northwest and southwest.

This peak and its landscape would surely be quite a spectacularly place to visit, should humans ever settle Mars and begin doing sightseeing hikes across its more interesting terrain. I can definitely imagine hiking trails coming up the two minor ridges, with a crest trail traversing the main north-south ridge across the peak.

This is not however a mountain on Earth. It is on Mars, which makes its formation and evolution over time fundamentally different than anything we find on Earth, despite its familiar look.

First, what formed it? Unlike most of Earth’s major mountain chains, the mountains of Mars were not formed by the collision of tectonic plates, squeezing the crust upward. Mars does not have plate tectonics. Most of its mountains formed either from the rise of volcanoes at single hot spots, or from the wearing away of the surrounding terrain to leave behind a peak or mesa.

This mountain however was formed from neither of these Martian processes, as the wide overview map to the right illustrates. The peak’s location is indicated by the white rectangle in the center of the image, on the southern border of the vast northern lowland plain dubbed Amazonis Planitia. While giant volcanoes flank it many hundreds of miles away, this peak is in an area with relatively few large mountains. It is also at latitude 17 degrees north, too close to the equator for glacial erosion.

In fact, the peak’s seemingly isolated location makes me think of the Lonely Mountain in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

What caused it if not volcanism or erosion? The answer becomes obvious if we zoom in to look at an overview map from much closer range.

That’s right, this peak forms the high point on the rim of two intersecting impact craters, whose total width is approximately 20 miles across.

Such peaks do not exist on Earth. Almost all of our planet’s craters have long since been erased by both erosion from wind and water and by those tectonic processes that do not exist on Mars. Thus, we have no mountains formed from the instantaneous impacts of two adjacent craters.

And instantaneous it likely was. While it is certainly possible for these two impacts to have occurred separately, at widely spaced times, it is more likely they came from the same large bolide that split as it roared downward through the Martian atmosphere, hitting the ground mere seconds apart. This Martian mountain will thus contain a lot of material ejected from below, with much of it reshaped quickly, from the gigantic heat and pressure created by those impacts.

Mountains on Earth do not form in seconds. The fastest forming are volcanoes, and while they might grow fast, they do not form in mere seconds.

And yet, that is how fast many mountains on Mars formed. Many thousands of craters still exist on Mars, and their mountainous rims are all like this one, formed instantly in time, despite the size of those peaks. It will a geologist’s dream to explore them.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

Those small holes on the very far south part look very interesting. Looks like a sponge or a pumice stone.

Interesting point, that nearby craters have a significant probability of having formed simultaneously from an asteroid that fragmented in the atmosphere or from gravitational tidal forces.

Earth has more and higher mountains now than ever. The collision of India with Asia forming Himalaya and the Tibetan high plateau is one reason. Mountain formation captures CO2 from the atmosphere and we were going down to levels below 0.02% where forests could not exist, until human industry started recycling underground carbon.

John C. Sorry to have not responded sooner. Those are not small holes. They are the shadows of many boulders, the kind of ejecta debris common at the base of crater rims.

The pumice stone analogy however has merit. Remember, this mountain and ridgeline was created when two bolides hit the ground side-by-side. The intersecting rim, of which this mountain is part, would have been well squeezed and heated in that impact.