Chicken Little rules!

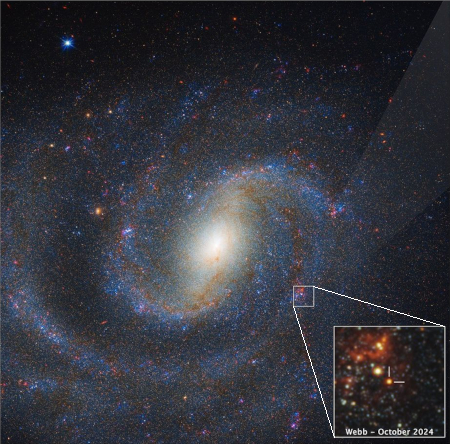

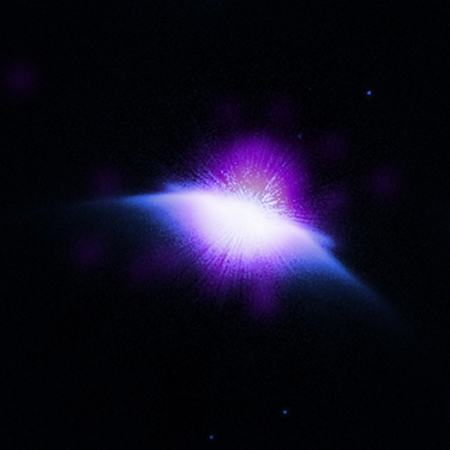

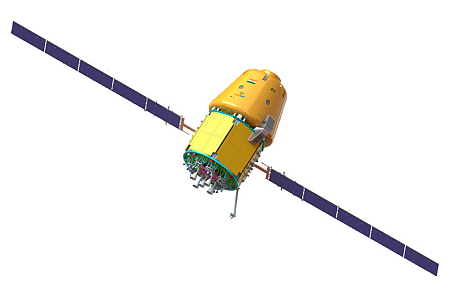

We’re all gonna die! In making the first direct measurement of the plume caused by the vaporization of the lithium in a SpaceX Falcon 9 upper stage as it burned up in the atmosphere, scientists now claim the pollution for those upper stages as well as the coming launch of tens of thousands of satellites is going to seriously harm the environment.

You can read their paper here. From its conclusion:

Beyond this single event, recurring re-entries may sustain an increased level of anthropogenic flux of metals and metal oxides into the middle atmosphere with cumulative, climate-relevant consequences. After oxidation and heterogeneous uptake on alumina and other metal-oxide particles, aluminium and co-injected species could perturb stratospheric ozone chemistry, modify high-altitude aerosol microphysics through new particle formation, growth, and coagulation, and thereby influence radiative balance. Key unknowns include emission inventories for rockets and satellites, lack of a systematic observational survey of mesospheric metals, altitude-time ablation profiles, chemical lifetimes, particle size-composition distributions, and transport pathways into the lower stratosphere. Addressing these uncertainties will require coordinated, multi-site observations (including resonance-fluorescence and elastic lidars, in situ sampling, and satellites), together with whole-atmosphere chemistry-climate modelling to connect event-scale injections to long-term impacts.

The problems with this study, and its conclusions, are numerous. First of all, this first direct detection of the lithium plume is really no discovery at all. We know the rocket’s upper stage carried lithium. We know it burned up in the atmosphere. It is plainly obvious that lithium would end up as vapor in the upper atmosphere where stage burned up. This detection simply measured what we already knew.

Second, the amount detected is really insignificant. At about 60 miles elevation the numbers rose from 3 lithium atoms per cubic centimeter to 31 during the stage’s burn-up, numbers that will quickly dissipate at these high altitudes. We are not talking big numbers.

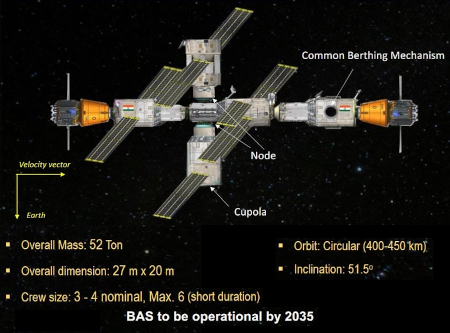

Finally, the threat from debris from upper rocket stages is only a temporary problem. As the demand to launch more satellites grows — which it will — the demand to recover and reuse the upper stages will grow as well. Already two American companies, SpaceX and Stoke Space, are developing rockets that will be completely reusable.

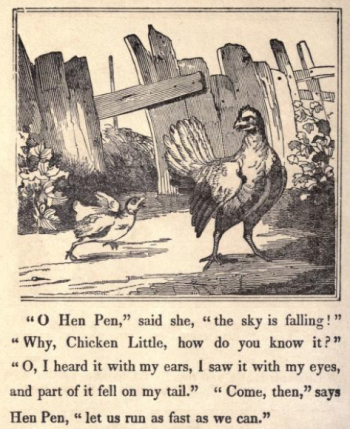

The mentality of these scientists is the same “Chicken Little” view of life held by the establishment science community for decades, from climate to industry to Covid to any human endeavor. “Everything humans do is bad! We must ban it now before it destroys us all!” And none of their cries of panic ever carry any larger context or reasonable perspective.

Sadly, this same attitude permeates the mainstream propaganda press. They don’t question such studies, they instead reprint their claims in bold, without any skepticism. We are thus ill-served by our so-called “independent and free” press.