Starliner’s troubles were much worse than NASA made clear

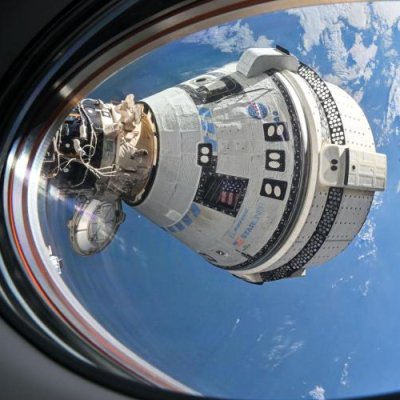

Starliner docked to ISS.

According to a long interview given to Eric Berger of Ars Technica, the astronauts flying Boeing’s Starliner capsule on its first manned mission in June 2024 were much more vulnerable than NASA made it appear at the time.

First, the thruster problem when they tried to dock to ISS was more serious than revealed. At several points Butch Wilmore, who was piloting the spacecraft, was unsure if he had enough thrusters to safely dock the capsule to ISS. Worse, if he couldn’t dock he also did not know if had enough thrusters to de-orbit Starliner properly.

In other words, he and his fellow astronaut Sunni Williams might only have a few hours to live.

The situation was saved by mission control engineers, who figured out a way to reset the thrusters and get enough back on line so that the spacecraft could dock autonomously.

Second, once docked it was very clear to the astronauts and NASA management that Starliner was a very unreliable lifeboat.

Wilmore added that he felt pretty confident, in the aftermath of docking to the space station, that Starliner probably would not be their ride home.

Wilmore: “I was thinking, we might not come home in the spacecraft. We might not. And one of the first phone calls I made was to Vincent LaCourt, the ISS flight director, who was one of the ones that made the call about waiving the flight rule. I said, ‘OK, what about this spacecraft, is it our safe haven?'”

It was unlikely to happen, but if some catastrophic space station emergency occurred while Wilmore and Williams were in orbit, what were they supposed to do? Should they retreat to Starliner for an emergency departure, or cram into one of the other vehicles on station, for which they did not have seats or spacesuits? LaCourt said they should use Starliner as a safe haven for the time being. Therein followed a long series of meetings and discussions about Starliner’s suitability for flying crew back to Earth. Publicly, NASA and Boeing expressed confidence in Starliner’s safe return with crew. But Williams and Wilmore, who had just made that harrowing ride, felt differently.

Wilmore: “I was very skeptical, just because of what we’d experienced. I just didn’t see that we could make it. [emphasis mine]

It wasn’t until SpaceX’s Freedom capsule arrived in September 2024, with two seats for Wilmore and Williams to use for return, that the Starliner astronauts finally had a truly reliable lifeboat attached to ISS.

All in all, the story here is that NASA last year took a very nonchalant attitude towards the lives of these two astronauts. Once Starliner docked to ISS, they really had no lifeboat in case a catastrophe occurred on ISS. The proper action at that point would have been to get a new manned Dragon docked to ISS as quickly as possible. Doing that however would have disturbed the complex planned schedule of dockings at ISS.

Being naturally lazy as all bureaucrats are, NASA management decided to instead take for them the easiest route, bringing Freedom to ISS in September as scheduled, even though it left these two humans without a lifeboat for a period of about four months.

Flying a quickly put together rescue mission also risked a lot of bad press, both for Boeing and for the Biden administration during the election campaign. (Biden’s fear was really unfounded. The press would have correctly lauded NASA and Biden for acting diligently and with speed.)

That both Wilmore and Williams are being so open and honest about these facts now suggests they either fear no retribution from the Trump administration, or do not ever expect to get another flight from NASA.

One lesson we all should take from this is to never trust any government officials from either party. In this case, I foolishly took NASA at its word last summer when it claimed Starliner was a safe lifeboat. They were lying however. And as much as I am always skeptical of government officials, I allowed myself in this case to be fooled.

And as they say, fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me. If I can at all help it, I won’t let this happen again.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

From the Ars Technica article:

Well, that was a lot worse than they were telling us. The astronauts themselves were holding back when questioned about it all, at least during the flight.

Flight rules are created for safety, so why would NASA waive the flight rules about loss of thrusters? Because not only did Wilmore think that the risk was greater to abort the docking maneuver than to continue it, even the NASA controllers thought so. What were they thinking, letting us believe that returning the astronauts in Starliner was an option? NASA had been a fairly open and trustworthy organization, with the Columbia disaster being an exception in which NASA didn’t even investigate the extent of the danger that they suspected, but hiding this amount of danger to Starliner allowed many of us to believe that Boeing had been screwed by the decision to return Wilmore and Williams on the Crew 9 mission rather than on Starliner.

If Starliner lost control over its six degrees of freedom, the astronauts were at risk of suffering a fate similar to the Starship 7 and 8 test flights. It is now clear that the Starliner service module needs an unmanned test flight after its redesign.

Robert wrote: “The proper action at that point would have been to get a new manned Dragon docked to ISS as quickly as possible. Doing that however would have disturbed the complex planned schedule of dockings at ISS.”

Making us feel as though the astronauts were safe was more important to NASA and the (lame duck) Biden administration than letting us know how bad the situation was. Thus, Elon Musk is correct. The decision to not send a dedicated Dragon was political.

More evidence that it was political:

https://spacenews.com/nelson-concerned-about-nasa-layoffs-and-other-changes/

If Nelson was not contacted, then NASA’s technical opinion was not part of the Whitehouse’s rejection of the idea. It was not a technical, scientific, or engineering decision.

“Wilmore added that he felt pretty confident, in the aftermath of docking to the space station, that Starliner probably would not be their ride home.”

Can’t help but wonder how far along that decision was in his mind after the docking experience. The final decision took some time to become public after all the testing. Testing that was, and still is, designed to show the thrusters can work under certain parameters and/or with minimal redesign.

If they were making political decisions, how much of a say did the astronauts get? They technically have veto power.

I bet they didn’t even have EVA suits which they could use to spacewalk over the ISS in the event they couldn’t dock. Something to consider if there is a next time.

“That both Wilmore and Williams are being so open and honest about these facts now suggests they either fear no retribution from the Trump administration, or do not ever expect to get another flight from NASA.”

I have absolutely no idea what Wilmore or Williams have planned for the future, or what NASA has planned for them (if indeed anything at all yet). But I do know they are 62 and 59 respectively, which makes them, from what I can make out, older than every active astronauts in the corps except for Don Petit. They’ve also spent more time in space than any of the active astronauts. So, I don’t think we should be surprised if they’re thinking this mission was their final one.

Which doesn’t mean that it’s not also possible that they feel politically protected by the administration, too.

And yet, Wilmore called the Starliner the “most robust capsule in the NASA inventory.”

Not sure if that’s PR talk or what.

https://archive.is/edMmV#selection-1245.0-1245.63

Hello Mike,

It’s not customary to have EVA suits on board any Commercial Crew flights. They’re very big and bulky; when NASA sends one up or brings one down, they always use a cargo vehicle.

I assume there’s some sort of contingency plan NASA has for a situation like that, where a crew vehicle is sitting disabled a short distance from the station. The astronauts would get into their pressure suits, and someone from the station scrambles into their EVA suits and comes out to EVA them over to ISS, as is (?), maybe using the Canadarm to help in the process. Needless to say, it would be a very high risk sort of option, only undertaken if the only alternative is imminent death for the astronauts.

Or maybe they have something better they’ve explored. I don’t know. But I have to think any last ditch rescue plan would be high risk.

Hello Gary,

Maybe we need Butch to unpack what he really means by “robust.”

Or, maybe his assessment has, uh, changed since then?

Interestingly, this question actually came up in the NSF forums at the time that happened (August 8). No one in the public really knew how bad the situation was at that point yet, of course, but perceptive peeps were already picking up on tensions in NASA’s claim.

One observer resolved it this way: “There is the question of why it is ok to use Starliner now as a lifeboat, but may not be ok to return to Earth normally. That was answered in the press conference: in a lifeboat situation, where clearly something serious and dangerous is happening with the ISS, NASA’s tolerance for risk is different to a normal return.” Going back to the presser recording and listening to what Stich was saying….I think this *probably* is the way we are meant to interpret what he said.

(Link: https://forum.nasaspaceflight.com/index.php?topic=60593.1300)

But this raises a new kind of concern: It seems misleading, and its seems like it’s meant to be misleading, even if it is carefully worded in such a way that no legal liability attaches. Because the missing term in this equation is just what NASA thought the level of risk now was. And from what Butch is saying, it sounds like that could have been shockingly high. Like, Gemini-level high, or maybe even worse. (No one died on Gemini, but those 10 missions were pretty arguably little short of playing Russian Roulette.) Only, a *shockingly* high LOC risk is still better than *certain* death, i.e., in a situation like catastrophic decompression of ISS, or an alien monster let loose aboard.

So maybe what we really have here is a sin of omission. If so, I think it’s worth asking why NASA managers did so. I think the idea, which was mooted over on X yesterday in Abhi Tripathi’s exchange with Eric Berger, is that NASA was, and still is, at great pains to support and protect Boeing. “Words spoken by NASA officials could really hurt a company and endanger future commercial efforts.” Eric pointed out what he thought was another example of this, when Bill Gerstenmeier stood strongly behind SpaceX after the loss of CRS-7 in 2015.

(Link: https://x.com/SpaceAbhi/status/1907482431353188606)

Of course, you and I might say that Boeing had exhausted the right to such public support by last August in a way that has never been true of SpaceX. But I suspect they’re probably onto a real motivation here.

I liked the book, The Martian. The film was not bad either.

Something I feel the film did better than the book was illustrate NASA’s absolute desire to control the narrative. It is actually something they have done since the beginning.

I want to know the conversation regarding the decision to bring Star liner down empty. What were the arguments. Who said what. I doubt we will ever get that transparency.

Richard M – You said: ” Like, Gemini-level high, or maybe even worse. (No one died on Gemini, but those 10 missions were pretty arguably little short of playing Russian Roulette.)”

Why?

Gus Grissom in his book Gemini: A Personal Account of Man’s Venture into Space published in 1968 praised the Gemini system and said that he thought there were many uses that the two person capsule could be used for even after the initial program was over.

Interested in more info and details on your statement.

Mike Borgelt

I don’t thing NASA has any other EVA suits other that the near 50 year old suits from the shuttle era. I doubt they would even fit in Starliner. Other than SpaceX, the US, China, and Russia have any operational EVA suits?

Publicly we all like to think of safety as a binary. In reality, it is a continuum. It is a a part of a western cultural myth that absolute safety is achievable or at least desirable. It is not socially acceptable to at admit that something might be less safe but you are doing it anyway, at least unless the payoff is huge. However, we make those decisions every day. You are accepting a fourfold increase in risk when you drive on a rural road rather than a freeway, for example. Yet most of us have done it for various reasons. We shouldn’t be surprised when our leaders do it as well. With Starliner, what they did seemed to be stalling tactics while they thought of a way to miraculously fix the thing or break the news. The public is very intolerant of risk in activities they think (erroneously) should be “safe” and “routine”. Something is either safe or not, no nuances involved, to our irrational minds. The human brain is prone to knee jerk reactions in situations like this NASA just had this in mind when considering how to spin it.

I thought the fact that Andy Weir made NASA’s chief PR flack a major character, and that Ridley Scott kept that, too, might have been the the most forceful contact with actual lived reality for both works!

Hi Thomas,

Please do not misunderstand me as criticizing Gemini! It *was* well executed, and it accomplished *exactly* what NASA intended it to accomplish. And what it was intended to accomplish was absolutely necessary as a prerequisite of attempting Apollo. It is too undeservedly forgotten as a part of space history!

But there is no getting around the fact that those missions were *hugely* risky. And NASA knew they were. The technology was so immature, the rush of time was so great, and the urgency of the task compelled levels of risk acceptance that no space agency today would dream of taking. Gemini was trying to do so many things that had never been done before.

Yes, the Enhanced EMU suits that NASA uses on ISS are so bulky that anyone wearing one could not fit through the docking hatch of a Dragon or a Starliner. When NASA brings one back for repair, or sends it back up again, they disassemble it and put it in a cargo ship. The only portal big enough to allow an astronaut to pass through wearing one is the Quest Joint Airlock on the US segment; or before it, the airlock that was typically installed on Shuttle orbiters.

It was called Commercial Crew but was a *test flight*. Appropriate to carry some emergency equipment for various emergencies.

4 person capsule with cargo space inside, surely room for even a couple of bulky spacesuits. Alternatively make sure there is something to turn the IVA suits into an EVA suit that enables survival for short periods, EVA. A small backpack. Put an umbilical on it so it can be pushed through the hatch first. In the original shuttle era there were pressurized rescue balls (never actually carried on with).

I think the main risk with Gemini would have been a booster RUD not long after liftoff. The ejection seat idea was scary. The Air Force MOL program was going to use Gemini.

Richard M – Thanks for your clarification. I think I would generally agree with your additional post; although I think they could be extended to the entire Mercury – Gemini – Apollo programs. I have watched closely the evolution of our US Space program since I was a first grader watching Alan Shepard’s Mercury-Redstone 3 suborbital flight.

My thinking has been that the US Space Program rolled the big risk dice during the Apollo program, where it departed earth orbit and ranged significantly farther into space. I recommend the book: Angle of Attack: Harrison Storms and the Race to the Moon by Mike Gray in this regard. Chapter 11 discusses the entire early safety factor and reliability discussion which set the mark for how the program was run.

Our discussion made me curious, so I used a modern tool, X’s Grok AI and asked the question: Which was the more risky US manned space program Gemini or Apollo?

I used the DeepSearch button and after 1,545 seconds it gave me about a 600 word relatively fact-based analysis for the answer of the above question. I will leave it to you to repeat if you are interested.

Thanks for the reply

There are a few problems, that could be overcome, with using the IVA suits as emergency EVA suits.

They first have to be able to be disconnected from the capsule and keep someone alive for at least an hour or so.

Second off they have to have, as mentioned, a way to tether from one ship to another. A simple rope could be used.

Does the suit have a ring to hook onto or will a harness have to be applied to attach the suit to the tether?

Does the capsule have an attachment point for the arm? Some way to keep the capsule close to and facing the station if it can not dock?

Could the ship have even made it close enough to the station?

This incident was far worse than they wanted anyone to know. It could have ended with two lost astronauts.

All because of an administration who wanted a win.

To Gary and Doubting Thomas.

Starliner has manual controls–so pilots would likely prefer that to full automation.

Titan/Gemini combos were hot rods…it has been said that Saturn IB/Apollo rides were like your Dad’s car.

But that’s what you want. Apollo could dock nose first and transfer through the nose.

I just hope this new F-47 NGAD deal has the same guys behind it as behind X-37… Phantom Works.

I would imagine so…

”I just hope this new F-47 NGAD deal has the same guys behind it as behind X-37… Phantom Works.”

Nope. The X-37 was designed and built in Seal Beach by the guys that built the Space Shuttle. The F-47 is being designed and built in St. Louis by the guys that built the F-15 Eagle, F/A-18 Super Hornet, EA-18G Growler, X-45A Stingray, and X-45C Phantom Ray. There’s heritage from the X-36 Tailless Agility Fighter and the Bird of Prey in there as well.

Good thing, too. The X-37 Future-X had a troubled beginning. After contract award years and years went by without much progress. So little progress, in fact, that NASA dropped the contract. It wasn’t until the Air Force picked up the contract and turned it into the X-37B that the thing even flew.

Starliner gives me the willies about Artemis. A lot of the same type “we’ll work it out” thinking. Do we really think that Artemis II has the known bugs properly corrected for a manned flight? Are they just going to “work it out” after liftoff?

If I recall Starliner had thruster issues in EFT-1 yet NASA took the word of Boeing they were corrected and put astronauts on EFT-2. And what problem did EFT-2 have? Thruster issues.

Edward says: “If Starliner lost control over its six degrees of freedom, the astronauts were at risk of suffering a fate similar to the Starship 7 and 8 test flights.”

Not so much Starship as Progress M-34 which ended up thumping Mir damaging both. Tough to protect the home turf if your incoming is out of control. Cheers –

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progress_M-34