The global launch industry in 2023: A record third year in a row of growth, with dark clouds lurking

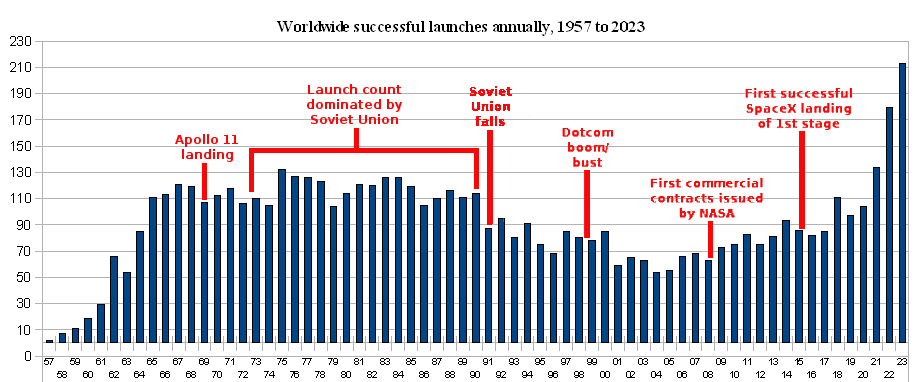

In 2023 the world saw a continuing rise in the global launch industry. As happened in 2021 and 2022, the record for the most launches in a single year was smashed. In 2023 nations and companies managed to complete more than 200 launches for the first time ever, with the number of launch failures so small you could count them on one hand.

Furthermore, if the predictions by several companies and nations come true, 2024 will be an even greater success. These predictions however all depend on everything continuing as it has, and there are many signs this is not going to be the case. More and more it appears the political world will act to interfere with free world of private enterprise, in some cases intentionally, in others indirectly.

Let us begin by taking a look at 2023.

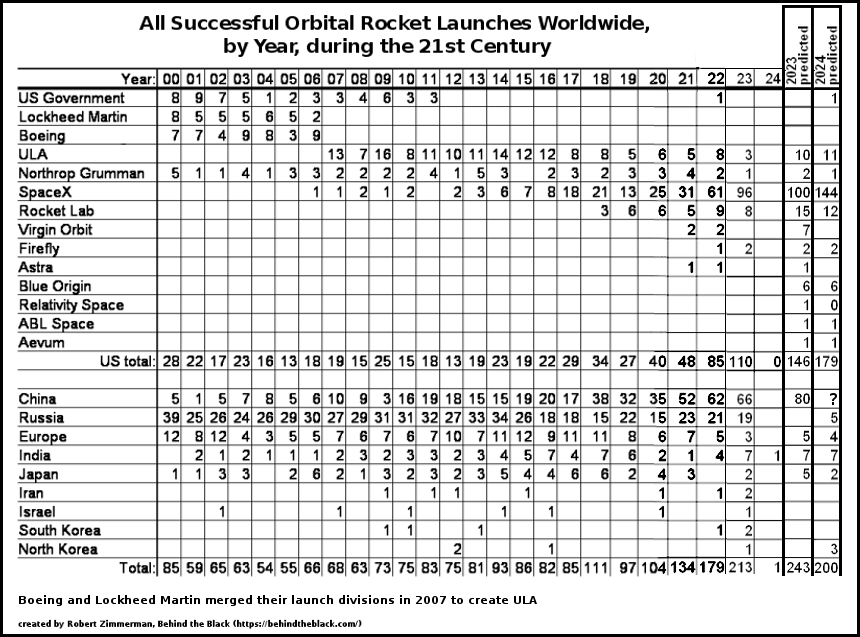

The graph above shows all successful orbital launches worldwide in the 21st century. There is a lot of information here to unpack, but the most important detail is the number of launches achieved last year, 96, by a single American private company, SpaceX. This number exceeds the number of annual launches by the rest of the entire world for the first two decades of this century, and in fact for most of the space age since Sputnik.

SpaceX’s success results from several factors. First the company pushed reuseuability in its rockets far ahead of everyone else so that now it can launch satellites at a cost so low it can easily beat the price of any other launch service, and do so by a considerable amount. It is likely SpaceX’s cost per launch on its Falcon 9 rocket is less than $25 million, and could be as low as $15 million. Since the average charge for other expendable rockets ranges from $80 to $200 million, SpaceX has a gigantic margin for profit while attracting lots of business.

Secondly, all of its competitors were mostly inoperative in 2023, because their new lower cost rockets that compete with the Falcon 9 were all behind schedule and not available. ULA’s older Atlas-5 and Delta family of rockets are being retired, with their few remaining launches already sold. Its new Vulcan rocket is four years behind schedule, with its first test launch now scheduled for January 8, 2024. Northrop Gruman’s Antares rocket is grounded because it had relied on an Ukrainian first stage and Russian engines, and those are no longer available. Its other rockets are too expensive. Blue Origin meanwhile continues to accomplish nothing with its New Glenn rocket, also behind schedule by four years.

In Europe its Ariane-5 rocket was retired this year, but its new Ariane-6 has not yet flown. Its Vega and Vega-C rockets are grounded because of launch failures. In addition, following Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine Europe broke off all use of Russian rockets, further limiting its options. Because of these facts, Europe has been forced to go to SpaceX for its launches.

Finally, SpaceX’s high launch count is further increased because of its aggressive effort to complete its Starlink satellite constellation. Of its 96 launches in 2023, 63 were Starlink launches, making it possible for the company to offer its internet service almost everywhere globally. As a result, the company now has more than two million subscribers and is bringing in enough cash to pay its costs.

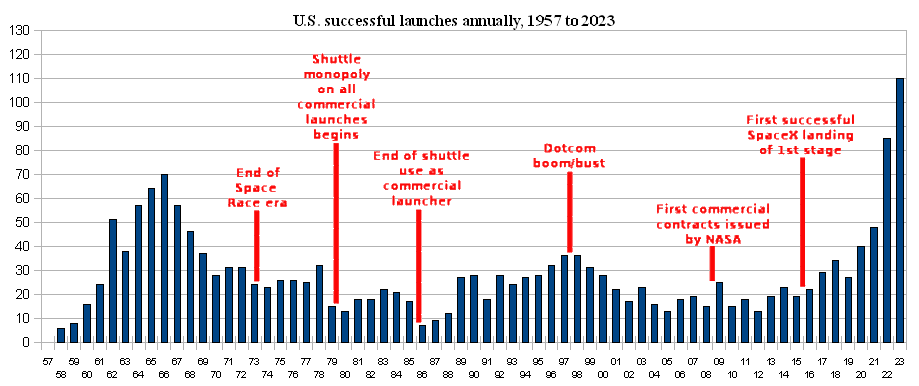

SpaceX’s dominance helps explain the sudden burst of activity by the United States in the past three years.

Nonetheless, the first graph above does indicate that real competition to SpaceX is just over the horizon. Both ULA and Europe expect their new rockets to become operational in 2024. Similarly, Northrop Grumman should resume launches relatively soon. Rocket Lab in turn expects to up the launch rate of its smaller Electron rocket to monthly in 2024, and is on the verge of beginning operations of its larger partly reuseable Neutron rocket, which will compete directly with SpaceX’s Falcon 9.

Of the smaller new companies, Firefly’s Alpha rocket has begun tentative operations. Blue Origin does appear to finally moving forward, with many unconfirmed indications suggesting it will achieve the first launch of New Glenn in 2024.

This is the positive news. There are also dark clouds on the horizon as well. Astra is no longer an operative rocket company, abandoning its Rocket-3 but now very short of cash and facing bankruptcy. Relativity is not short of cash, but after one test launch of a smaller rocket it decided to switch all work to developing a larger version, thus delaying further launches for several years.

Virgin Orbit is out of business, a bankruptcy largely caused by the United Kingdom’s government when its regulatory body, the Civil Aviation Authority, delayed issuing a launch permit for almost all of 2022. During that time the company could do no other launches, earned no revenue, and when the UK launch finally occurred and failed early in 2023 it no longer had the resources to recover.

Similarly, at the start of the year it was expected that both ABL and Aevum would attempt to reach orbit in 2023. Neither did so. ABL’s first launch failed in January, but though in October it announced it was gearing up for a second attempt that attempt has not yet occurred. Aevum, meanwhile, did nothing the entire year, though in 2022 it seemed close to that first launch.

It appears that not just technical issues have been a problem. The same regulatory clouds that killed Virgin Orbit in the UK appear to have risen in America. SpaceX for example experienced significant delays in the developmental launch schedule of its big Superheavy/Starship rocket. In 2022 it had said it wanted to do about six test launches per year, continuing the fast pace of Starship tests from 2020 and 2021. Slow action to approve launch licenses by the FAA and the federal government blocked that effort. Instead of doing between 6 to 12 test flights, SpaceX only did two, and remains blocked by the FAA for its third.

There is a strong possibility this new intransigence by the FAA has also slowed the launch pace for these new companies. During the Trump administration it appeared that test launches by many companies were frequent and varied. With the arrival of Joe Biden all that changed, with the FAA and other agencies suddenly demanding much more control and supervision. This change thus might have been a factor in why both Astra and Relativity abandoned test launches of their smaller rockets. Too much new red tape made both impractical.

Thus, the burst of growth in the American rocket industry in the last decade might be facing a serious bump in the next decade, squelched by increased regulation by the federal bureaucracy.

We must also factor in the unknowns relating to the coming 2024 presidential/congressional elections. The seriously unstable political situation in the U.S. could impringe badly on the space economy, in ways that are right now unpredictable.

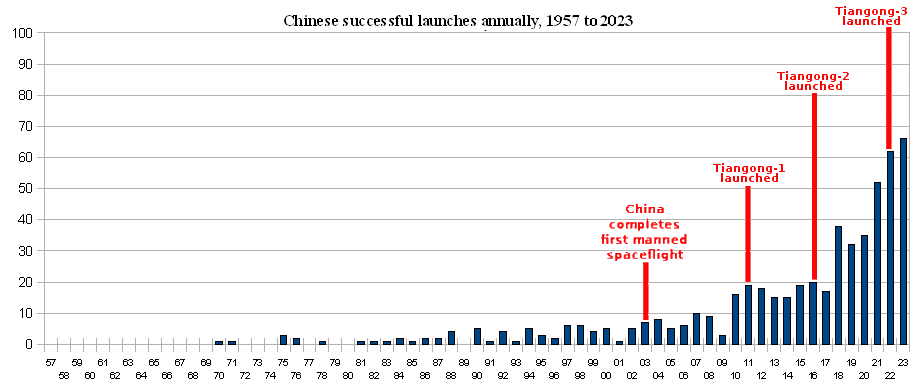

Meanwhile, as shown in the graph above, China’s space program has continued the growth that began at the start of this century. Its Tiangong-3 space station is now completed and occupied full time, with plans to expand the station. The program has big plans to explore the Moon and Mars. And it is using a pseudo-system of private enterprise to generate competition and innovation, allowing private citizens to form companies, raise capital, and develop their own rockets so as to make profits by winning government contracts.

None of this is actually private, however, since these new pseudo-companies are all closely supervised and controlled by the government. They do nothing without its approval, and should that government wish to take over a company, it can do so at any time.

Nonetheless we should expect China’s space program to continue to grow. It has laid out a very rational and thoughtful program for the exploration of the solar system and has been following through on that plan.

More important, the government has been using space to train its future governors and political rulers. A large number of China’s political leadership came out of its space program. These people will thus be favorable to continuing that program, even if they themselves are now in purely political roles and no longer part of it.

Whether this will happen however does depend on China’s economy remaining as it is. There are signs however that China faces the same instabilities as the U.S., all of which could cause a crash that will shut down space exploration.

Then there is India. During the COVID panic its space agency ISRO stumbled badly, shutting down while others continued to fly. Since then however that agency has shown signs of revival, fueled partly by new competition from the private sector. The Modi government has aggressively moved to imitate NASA and transition from having ISRO build, control, and own everything to becoming simply a customer that buys its space products from the private sector. New Indian rocket companies are moving forward, and we should expect this country to do some exciting things in the coming years.

The other countries on the first graph — Japan, Iran, Israel, South and North Korea — are all minor players at this point. Iran in fact is very minor. For example, it is still unclear whether its second orbital launch in 2023 actually reached orbit.

Japan remains the biggest disappointment. It has relied entirely on a government-run space program, and its space agency JAXA has generally failed in that effort badly. It has retired its older very expensive H2A rocket, but its new H3 rocket has had serious development problems and is still very expensive and non-competive. Worse, unlike India there seems to be little effort in Japan to change things.

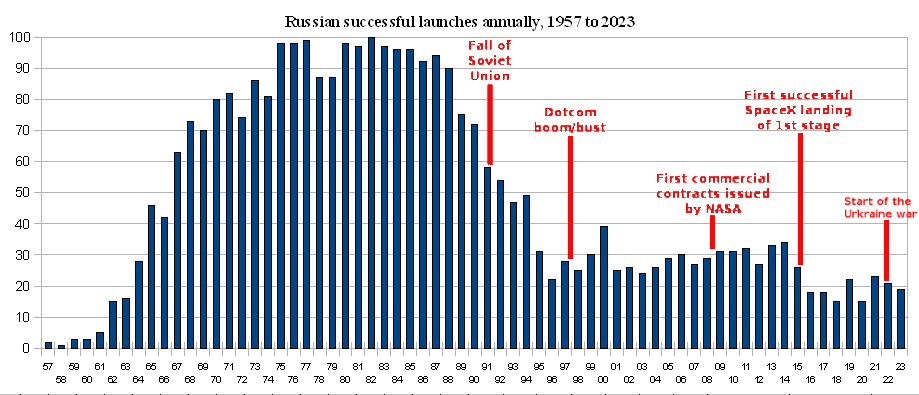

Finally we must conclude with Russia and its continuing decline as a major space power. It lost about a billion dollars in space revenue when it invaded the Ukraine, with all of its customers abandoning it. It no longer has the cash to launch any new projects, and even when it does it sees its space program more as a jobs program. It doesn’t matter to it if anything ever flies. Keep that pork flowing to the old government agencies that run space but do little, and everyone is happy.

Thus, no one should take seriously any of Roscosmos’s future plans. As has been the case now for more than two decades, nothing will happen, or if it does it will be years late, with an excellent chance of failure when it does fly.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

Related technologically:

“Everybody Wants to Rule the World”, an appropriate song choice for this exclusive TESLA EV involved 2023 show of how robots can on a central command work in unison. But what are the overarching implications of this very impressive demonstration?

Read and remember to share on social media with the politically bewildered in your life………….

https://www.sigma3ioc.com/post/absolute-control-what-are-the-implications

Excellent reading. I always look forward to your annual round up.

You lay a lot of blame on the UK’s CAA for Virgin Orbit’s failure. But I do not believe that is the full story.

It clearly played a role, but since most flights were out of the Mojave, I cannot agree this played as big a role as thought. In fact, part of the blame should be on VO for moving assets and preparing for the launch before the CAA had given them a go. It was a bold play to show “flexibility” of air launch being able to go anywhere. The play failed.

They carried huge debt, and burned cash fast, instead of tightening the belt. An example: “Two people mentioned wastefulness in ordering materials. For example: The company would buy enough expensive items with limited shelf-life to build a dozen or more rockets, but then only build two, meaning it would have to throw away millions of dollars’ worth of raw materials away.”(https://www.cnbc.com/2023/03/31/virgin-orbit-what-went-wrong.html)

SpaceX’s rideshare flights launching dozens of small sats at once is a large draw on the market, putting the VO price tag out of reach

at 12 Million or $24k/kilogram for VO (Wikipedia) vs $3 to 5k/kilogram (SpaceX) At the time of collapse, they had little back log.

They were also led by a handful of ex-Boeing (aka, old space) execs. I cannot say, but in reading a few comments on social media by former employees, this played a role.

With this kind of operation, and killer competition, they had little chance of success. The CAA debacle in the UK, as well as their own failure, simply expedited the end, in my opinion.

On a separate note, I am surprised you did not mention the pending/potential ULA sale.

sippin_bourbon: Excellent additions to my report. Thank you.

1. Though I know some of the blame for Virgin Orbit’s failure belongs to its management, all would I think have been okay had not the government put its thumb on the scale, quite incompetently. Also, the tendency of journalists today to provide cover for government incompetence and abuse of power requires me to underline it, when it occurs.

2. The ULA sale is likely, but its ramifications are entirely unknown until we know who the buyer is. The variables are large, depending.

It’s still happening …

“Its new Vulcan rocket is four years behind schedule, with its first test launch now scheduled for January 8, 2023.”

Call Me Ishmael: Thank you. Fixed.

Blue Origin: I don’t remember 2021, but in 2022 they had an announced goal of getting a pathfinder vehicle to the pad. It didn’t happen. Even though it had been a goal for 2022, it was still a “by end of year” goal for 2023. And they didn’t make it. Equipment has been seen moving around, and there are better noises coming out about management changes and progress, but if they don’t get that pathfinder to the pad in Q1, we might as well move the prediction to first launch in ’25.

David Eastman: I only have one word in response: Yup.

Put an Electron rocket on a Russian Proton rocket and you have the new Hydrogen Launch Vehice.

Mr Z,

Question about your initial chart.

Is the 2024 Prediction column your prediction, or the countries/companies plan?

sippin_bourbon: The 2024 prediction column is mostly taken from the list of launches posted at rocketlaunch.live, supplemented by news stories I have linked to previously. As more information becomes available in the next few weeks, I will amend it on my spreadsheet. The most significant number will be China’s prediction for 2024, as it will likely add 50 to 80 launches to the total.

Thank you.

I was curious, as Rocket Lab suggested a 22 launch year in the last quarterly results presentation.

Two of those were Haste, so sub-orbital, of course, which you do not track, so 20 for your purposes.

This is their stated goal, anyway, working on the assumption of no failures.

It was sad to see their failure, as I think they would have at least gotten close to the 2023 goal.

Col Beausabre: Well Played, Sir.

sippin_bourbon: Gosh, I forgot about that quarterly report. 20 is the correct number, even if Rocketlaunch.live only shows 12 orbital launches. I will amend the spreadsheet.

Virgin Orbit’s timing was awful. Virgin Galactic started working on air launch in 2009. First launch didn’t happen until 2020. That failed, which is par for the course. Finally launched something in January 2021. SpaceX launched the first Transporter mission that same month. The bottom subsequently fell out of the small launcher market.

I agree that Virgin Orbit had other problems people have mentioned. But, they moved slowly and by the time they were up and running, the market had changed.

sippin_bourbon,

I disagree with you on many of your points.

“The company would buy enough expensive items with limited shelf-life to build a dozen or more rockets, but then only build two, meaning it would have to throw away millions of dollars’ worth of raw materials”

This is an indication that they had plans to launch many times, to increase their launch cadence. They expected growth, and if they don’t buy the hardware for building rockets then they cannot grow. This is yet another factor that shows how bad the British delay was to the company.

“In fact, part of the blame should be on VO for moving assets and preparing for the launch before the CAA had given them a go.”

That may seem clever in 20/20 hindsight, but if you are going to tell the full story, then you should not leave out important parts. The British government had expressed its eagerness to host this launch and for Britain to be a friendly place for orbital launches. The problem is that the regulators are just too lazy to carry out their own government’s policies.

Launching from Britain was a brilliant move for public relations and marketing. It indicated by example, not just by vague promise, that their launches are flexible. The promise broken in this case was not Virgin Orbit’s but the British government’s. Had the British government been honest with VO and told it that it would take five months after the scheduled launch to give launch permission, the company would have had an opportunity to locate assets to launch another customer or two. Instead, Britain just neglected the company and left them hanging.

Virgin Orbit’s planning and management are not to blame here. They were acting in good faith with their European and British customers, but the British government betrayed the trust that VO put in them.

“They carried huge debt, and burned cash fast, instead of tightening the belt.”

Once again, this cannot be faulted on Virgin Orbit but on the British regulators. Virgin Orbit was expanding its business into additional areas, but had the launch occurred on schedule in September, then the failure would have been known before a lot of money was spent on the expansion efforts. The company could have reassigned resources away from the expansion and into fixing the problem, and they would have had an additional five months of savings to weather the storm.

Had the British government been honest with VO and told it that it would take five months after the scheduled launch to give launch permission, the company would have had an opportunity to tighten their belt. Instead, Virgin Orbit had no reason to believe that they should review their expansion plans.

“SpaceX’s rideshare flights launching dozens of small sats at once is a large draw on the market, putting the VO price tag out of reach

at 12 Million or $24k/kilogram for VO (Wikipedia) vs $3 to 5k/kilogram (SpaceX) At the time of collapse, they had little back log.”

At the time of the collapse, VO expected seven launches for the year, six in addition to this one. If you are going to tell the full story, complete the story.

To come closer to completing the story: the Transporter launches (rideshare) cost the customers $275,000 for the first 50 kg and $5,500 for every kg after that. If your satellite is less than 50 kg, you pay more than $5,500 per kg, and only to sun-synchronous orbit. This series of orbits are not optimal for all satellites. We desperately need more customized launchers to take smallsats to their optimal orbits. I have talked to a couple of people who make smallsats, and they lament the loss of VO. These guys were upset because the Transporter launches are only limited in their usefulness. They are only somewhat better than piggyback launches. As Robert noted, Astra and Relativity have also left the smallsat launch business, but not for lack of smallsats that need launching.

https://www.spacex.com/rideshare/

“With this kind of operation, and killer competition, they had little chance of success.”

I know! Right? The competition killed Rocket Lab, too.

Oh, wait …

These are some great graphs, and they are going into my files.

One thing you do not list out, Bob, is that virtually all of those SpaceX launches also *landed*, which still makes them unique in these data sets, at least for the moment. (This is not a complaint. You have to limit your data somewhere!) I bring this up because there was an interesting exchange just now about retropropulsive reentry on Space Twitter, which illustrates why a company like SpaceX succeeded in doing this, and a government agency like NASA never did. And it is not because NASA employs dumb engineers.

__________

Peter Hague: “A lot of people don’t realise just how clever the reentry burn is. Your rocket engines create their own transient heat shield.”

Jeff Greason: “I was staggered back in 2009 when I was told this was considered a super-high risk technology for Mars EDL. “Rocket flow is supersonic, the engine doesn’t even *know* it’s in a retro flow, what’s the worry?” “Too risky”. Now SpaceX does it every week.”

Phil Metzger: “True story about this you will likely find interesting.

Right after SpaceX started crashing rockets into barges and hadn’t perfected it yet, I met a young engineer who was part of NASA’s research program for supersonic retropropulsion. He said at NASA, we had a big program planned to study this.

We were going to start with lots of computer simulations.

Then we would put a thruster on a high speed rail car and shoot the plume into the direction of travel.

Then we’d drop rockets off high altitude balloons…

But then @elonmusk just went and tried it, and it WORKED! So NASA canceled our entire program!”

😂😂😂

The beauty is that SpaceX didn’t even have to land on the barge for this result. Just hitting the barge with the booster proved that supersonic retropropulsion worked.”

I find the potential that Blue Origin buying ULA interesting.

If Jeff Bezos buys it, he buys an operational competitor to SpaceX.

An expensive way to get back in the game, but at this point, maybe his only way back in the game this decade (some sarcasm there, just taking a swipe at his companies pace).

I am not familiar with Textron’s outside of Aviation, Maritime and a few agricultural concerns.

I know they are large, but would this be a new venture for them?

Anyone familiar with them know if their tech has gone to space before?

Same with Cerebus. They are an equity company with a reach in to many sectors.

Mr Messier

You said “The bottom subsequently fell out of the small launcher market.”

I believe you overstate this. The bottom did not fall out of the market.

(Also, the phrase means people stop buying a product/service, and thus no market for maker/provider in which to sell. I believe you meant to imply that SpaceX established a monopoly or near to it, and will go with that.)

They did however, provide a draw that smaller and less successful companies could not compete in.

SpaceX launched 70% of all small sats, between 2018 and 2022. But most of those are Starlink.

They only take 10% of the market once Starlink is excluded.

Soyuz was taking 7%. But with their launches dropping, and no rise in site as long as the Ukraine war continues, I would expect this to drop.

VO was getting less than 1%. That appears to include successes and failures based on how this is reported.

SpaceX, and others, are killing it.

Small launch vehicles launch 29% of all small sats in 2022, excluding Starlink and One Web.

(Source: BryceTech)

Edward

“This is an indication that they had plans to launch many times, to increase their launch cadence.”

Of course they had plans but it does not matter. It was still millions down the drain. It was poor planning and poor inventory management. The 5 month delay by the CAA did not cause that, it was already happening. The quote I gave was provided by Virgin Orbit employees. Another employee said they ”launched the same amount of rockets in a year with a staff of 500 as it did with a workforce of over 750 people.” That also implies an issue predating the CAA delay.

“That may seem clever in 20/20 hindsight, but if you are going to tell the full story…”

“Launching from Britain was a brilliant move for public relations and marketing…”

I stated it was a bold play on VO’s part to show flexibility. (you may have missed that). The play failed because of the UK Gov/CAA and the failure to successfully launch the payload. But it would not have been fatal for VO had they had not lost almost $140 million in the 9 months leading the last launch. They had an $821 million operating deficit in 2021. Again the money the problem predate the delay.

“Virgin Orbit’s planning and management are not to blame here.”

They are to blame for the weak position they were in going into this planned launch. Had the mission been allowed launch timely and had it succeeded and, they might have had an opportunity to dig themselves out, but only with a massive change in how they were operating and using funds. They should have managed assets and manpower better to start.

“Had the British government been honest …”

You imply that I am letting the UK Gov/CAA off the hook. I assure you, I am not. Just that it was not solely to blame.

“The Transporter launches (rideshare) cost the customers $275,000 for the first 50 kg… and only to sun-synchronous orbit. This series of orbits are not optimal for all satellites.”

They also do rideshare to LEO, according to the SpaceX Rideshare Program site. I see SSO and LEO, none to Polar at this time. And it is $5k to 6k/kilogram. I stand corrected. It is still significantly less than VO offered. The biggest provider is still providing lower cost.

“We desperately need more customized launchers to take small sats to their optimal orbits.”

Not disagreeing, nor questioning that the loss of VO was lamented by many. I did not suggest SpaceX owns the market, but they do have the lion’s share.

VO had 6 launches, 4 successful, at 12 million a pop, that limits customers due to price and reliability. Their backlog was shrinking, implying customers were looking elsewhere.

“Astra and Relativity have also left the small sat launch business, but not for lack of small sats that need launching.”

“I know! Right? The competition killed Rocket Lab, too.”

I have not suggested there is a lack of small sats that need launching. Only that SpaceX is taking most of them, and that is after excluding Starlink. (also Bryce tech, Small sats by the numbers 2023).

Your sarcasm is highly misplaced. My analysis was limited to VO, not the small sat market as a whole.

I have not responded to your posts for sometime, as you tend to put words in my mouth or make assumptions about what I am saying. I am not sure why. I am hoping we can converse on the topic civilly.

I have additional thoughts on things I see in this report.

Robert reports that SpaceX likely spends less than $25 million on Falcon 9 launches. Since they charge a little more than $60 million, that means that the Falcon launch division makes a profit of more than $35 million per launch, or around $3-1/2 billion dollars in 2023 (if we consider Starlink as a separate entity, which may be fair, since there may be investors in only that part of the company). Considering that Starship development is currently costing about $2 billion per year (now totaling around $5 billion), SpaceX could be funding Starship without any outside investment.

If we remove the SpaceX launches from the U.S. totals, we can see that the U.S. launches are pretty much level, averaging under 20 orbital launches per year. This is not a fair analysis, because Falcon and Falcon Heavy took some launches away from ULA, which has a reduced launch rate. The reduced price tag of a Falcon launch had disrupted launch business worldwide. Once SpaceX showed that a booster could be reused, everyone realized that their prices would permanently be undercut by SpaceX. Many launch providers chose to redesign their boosters to cost less to produce and cost less to launch. Efficiencies would be easy to find, as there was no real competition around the world, and most launch providers had concentrated not on price efficiency but on technical efficiency and high reliability.

Red Adaire is said to have said something like, ‘I can do it fast, I can do it well, or I can do it cheap. Choose two.’ Usually, it takes time for an industry to improve on these three concepts in their products, but SpaceX made a leap in both price and availability without compromising reliability. With SpaceX, you could get all three. ULA boasted of their reliability, but that came at a high price and a low launch cadence. The rest of the launch providers needed to catch up to SpaceX’s abilities, and this led to the difficulties that these providers are having with their new rockets. At the same time, a couple of NewSpace providers started up and designed new launch vehicles that would compete better with the Falcons, but these new vehicles are still working toward first launch.

It is due to these new competitions and the low launch prices that we now have many companies entering the space business, generating revenue through activities in space. This is why we have the increase in the number of annual orbital launches. Governments used to be the major customer for launch services, but commercial companies are now the major customer. This is why we have more launches than ever before. The governments are not increasing their use of space, but We the People are.

SpaceX predicts 144 launches in 2024, which means that they believe they can make around a gross of Falcon upper stages. That is a lot of rockets, more than the traditional OldSpace companies had done. I think it was Relativity that made an entire rocket from additive manufacturing (3-D printing). A few years ago I was amazed that so much of a rocket engine could be made from 3-D printing, but now whole rockets can be, although Relativity has said that their larger rocket will not be entirely 3-D printed. These are major changes in the industry. Who needs a jobs program on the taxpayer’s dime when commercial space is eager to provide jobs making, launching, and operating satellites, probes, and space stations?

Small satellites are making a comeback. They were popular in the 1960s, as there were not a lot of launchers for large satellites. The time and cost to build smallsats is low, and the cost to launch them is low, so this allows for affordable and quick replacement as technologies improve. We see smallsat launch companies taking the place of the OldSpace Scout launch vehicles.

Robert’s numbers and charts don’t explicitly show the advantage of commercial space over government space, but by adding information that the U.S. companies listed on the first chart from SpaceX downward are commercial companies, whose launch vehicles are designed not for government payloads but for commercial payloads, we can see that these commercial companies thrive better than the OldSpace companies, which have depended upon government payloads. NASA had been the bastion of innovation and technology, but that reputation had been lost during the Space Shuttle era. SpaceX has replaced that function, boldly making revolutionary improvements in methods and technologies in space access and operations, and it isn’t doing it for national prestige, like China is doing, or to win some space race, and it isn’t costing taxpayer money. It is doing it for profit, finding efficiencies and new technologies. No wonder the company is so successful.

This is a major shift in our use of space. Despite it being commercial, all of mankind benefits more than it did when government was the major player in space, and this does not cost the taxpayers. Government was in space for its own purposes, not for the purposes of all mankind.

Robert’s charts don’t show how politics interferes with the construction of new launch sites. The elected leaders in a county in Georgia, USA, was willing to host a new small launch site, but the county’s population voted against it. It may be difficult to create new launch sites, despite several states having declared small airports to be spaceports. Texas’s Brownsville and its county may be eager to host a launch site, but not all areas are equally eager. Robert noted other political interferences.

Usually, regulatory clouds are difficult to see, which is a reason overregulation can easily exist, but with Starship the interference is obvious and glaring. So many people closely watch Starship’s development that we can see just how ready SpaceX is for its next tests, and we can see they are ready months before the regulators reluctantly accede to public pressure and give permission for the next test launch. We have seen the result of poor regulatory oversight in other industries, too, when baby formula was hard to find, when freighters were lined up at entrances to ports, and when shortages abounded a year or so ago. As a wise U.S. president once noted: government isn’t the solution but is the problem.

Robert mentioned the possibility that the FAA’s overregulation of the launch industry “might have been a factor in why both Astra and Relativity abandoned test launches of their smaller rockets” in order to develop larger vehicles. “Too much new red tape made both impractical.” Smallsat launches generate less revenue than the heavier launches. If the red tape is the same, then these companies might as well go for the high-priced launches instead. Joe Biden complains that companies are charging too much money for their products, but these overregulation policies visibly cause increased costs to the launch providers and reduced supply to the satellite operators. If he wants lower prices, he has to make it possible. That the man doesn’t understand third-grade economics explains so much of why government has been such a screwup during his tenure in the U.S. government. It is no coincidence that the U.S. did so well for the four years when he was out of government between his time as Vice President and his disaster as President.

If a company cannot even get permission to return a medical product made in space, what the hell are we paying taxes for? The demand for that product exists, but there is no supply to satisfy it. What good is government if it actively stifles our livelihoods, innovations, and healthcare?

I am eager for future years, when commercial space stations will need a significant part of the world’s launches and when commercial manufacturing in space will need another significant part.

Edward noted that “Usually, regulatory clouds are difficult to see.”

This is why the last thing journalists should do is provide any cover for government agencies. It is the job of reporters to dig, to question, and above all, doubt the sincerity and innocence of government officials. That’s why a free press exists, fundamentally. For that press to play defense for government officials means it has essentially abandoned its purpose.

The whole Starship regulatory story revealed these facts about the press most starkly, and sadly among the press that covers the space beat specifically. Too many space beat reporters and outlets have refused to admit the government was abusing its power. Too many still refuse to admit this. Instead of doing their job, they have become government agents, to the detriment of the very industry it is their job to cover.

sippin_bourbon,

If quoting your own words is me putting words in your mouth, I really don’t know what to say in response to you. I use quotes in order to avoid that complaint. I don’t know how we can converse civilly when you deny your own words. Your previous policy may be best, and we should both agree to not respond to each others’ comments.

_____________

Robert wrote: “Too many space beat reporters and outlets have refused to admit the government was abusing its power.”

The result is that many people in the public also defend the oppression of the overregulating governments.