Tiny crowded Israel

Much of the world’s political troubles are centered on the question of Israel in the middle of the Middle East. In both the Arab world as well as in some western intellectual circles, there are whole campaigns to make it go away (some peaceful, some genocidal). Politicians, pundits, and intellectuals argue incessantly about the rights of the Palestinians and the Jews, the best solution of achieving peace, and even the question of whether the Jews who have immigrated there have a right to stay.

I have just returned from spending two weeks in Israel, a trip I do somewhat regularly to see family. Each of these visits has given me an on-the-ground close-up look at the situation there, something that is difficult to get from the typically shallow media coverage of the region. And from each of these visits comes at least one essay, something I think is required because of Israel’s significance in much of the world’s political turmoil.

This year, we took a three day sightseeing trip to northern Israel, to visit some Roman ruins, the Sea of Galilee, and an incredible nature preserve that is the springtime home for thousands upon thousands of migrating birds. This excursion thus made this particular Israel visit far different from my half dozen or so previous trips, in that it was the first time I spent a considerable time in Israel proper. All my previous trips visiting family had me spend almost all my time going from one West Bank settlement to another. (That experience resulted in a series of essays on what those settlements are really like, which not surprisingly has no resemblance to their portrayal in the western press. My previous essay, A look at some Israeli West Bank settlements, provides a good summary, but it also provides links to all the previous essays, which are definitely worth the time to read if you want to find out what it is really like in the West Bank. I will give you one clue that might shock you: Hitchhiking is one of the most popular ways to get around.)

Anyway, this three-day trip allowed me to get my first look at Israel itself. The map above shows our route, as indicated by the dotted red line. The numbered Xs were our stops, of which I will discuss below.

Israelis will often and repeatedly talk about how small their country is. Unless you have been there and spent some time traveling within it, however, it is difficult to gauge exactly how small it really is.

It is small. It took us only about two hours to drive from the West Bank settlement of Beitar near Jerusalem to stop #1, the town of Reheshem (a suburb of the city of Haifa) where we would stay the first night. From there, it was only about a 20 minute drive to stop #2, the ruins of the ancient city of Tzippori, and only another 20 minutes to stop #3, Tiberius on the Sea of Galilee. From there we did day trips to stop #4, the Hula Valley Nature Preserve, and stop #5, the ruined remains of the Roman city of Scythopolis, with the travel distance one-way to each only about a half hour.

In other words, once we reached the northern area of Israel near the Galilee Sea, from its center we could pretty much reach any point in that region in only about 30 minutes of driving. No matter what direction you went, you simply could not go very far before you reached the ocean or a border checkpoint. For most Americans, these travel times wouldn’t be enough to cross the cities they live in. And to get from this north region to the country’s narrow waist, where Jerusalem sits, took only about two hours. It was kind of like driving from southern New Jersey to Manhattan, or from Chesapeake Bay to Washington, D.C.

To put it mildly, Israel is tiny.

It is also crowded. In the north the countryside was mostly intense agriculture, but it also was constantly interspersed with small hillside cities (both Jewish and Arab and sometimes mixed) and factories and shopping and urban patches. In fact, much of it reminded me of either suburban Maryland or New Jersey, which as you drive farther from the big cities the countryside slowly transitions from strip malls to farming, with lots of homes and developments in-between. And like Maryland or New Jersey, you never get out into areas where few people live. The roads are busy with lots of traffic, even when things look the most rural.

Of course, this is the lush north of Israel. South of Jerusalem is the Negev Desert, where the bulk of the country’s territory is and where almost no one lives. Nonetheless, the northern half of Israel is active, crowded, and small, and resembles the rural suburban areas that surround most big American cities.

To give another example, consider the picture below. I took it during our visit to the Hula Valley Nature Preserve, stop #4, which during the spring months acts as the home for thousands of migrating cranes. We rented bicycles so that we could quickly circle the park’s central lake/swamp, where the cranes were gathered in gigantic and noisy numbers. This picture was taken on the lake’s west side, looking east at the many cranes in the park’s swamp area.

What I didn’t realize when I took the picture was that the hazy ridge in the background, only about 2 miles away, was actually the Golan Heights. In fact, twice during the day I heard a loud sudden rumble, sounding somewhat like thunder but too short and inexplicable because the sky was clear with no thunderclouds. It wasn’t until later that I realized that those rumbles were probably the sound of bombing. Note on the map above the small patch of ISIS-controlled territory tucked into the southwest corner of Syria. Recently Israel and the Syrian opposition forces have been working together (covertly) to wipe out this ISIS pocket, with the Israelis providing air support while the opposing forces do ground operations. The rumbles I heard were almost certainly bombing runs by the Israelis, just on the other side of the ridge in this picture.

Similarly, when we visited the ancient ruins of the Roman city of Scythopolis, stop #5, I climbed to the summit of the steep hill called Bet She’an on the north side of the ruins. From there, only a few hundred feet above the surrounding terrain, I took the picture below, looking east across the Jordan River into Jordan itself, with the small town of Shaykh Husayn on the lower right and the larger town of Waqqas to the left and nestled in scattered patches close to the mountains. Both towns are no more than six miles away, with the border itself about four miles away.

In fact, from this summit I could look into the West Bank to the west and to the south, equally far away.

It was this very strategic location, which also included ample water and was at the junction of both north-south and east-west roads, that made this hilltop so valuable. While most of the ruins found here now date from the Roman era and later, on the summit archeologists have found twenty layers of past settlement, going back to the Egyptians. This was a place fought over by the Egyptians, Israelites, Philistines, Romans, and now modern Israelis and Arabs. The land was good, and everyone wanted it.

Yet, despite the close proximity of these borders and the strategic value of these locations for all concerned, these tourist sites had numerous visitors, from families with toddlers to larger American Christian tour groups. It was surreal. Ordinary life on the surface seemed to go on undisturbed, even as a war was rumbling on the very near horizon.

In many ways, this nonchalance reinforced my conclusions back in 2013 about how relatively safe Israel is.

In fact, in Israel in general there is practically no violence or violent crime. The only violence that occurs in Israel is when a terrorist act takes place, which though relatively rare immediately gets trumpeted in all the newspapers and internet news sources worldwide. Imagine if every crime in Chicago, which take place far more frequently than terrorist acts in Israel, was given that kind of attention. We would all consider that city to be far more dangerous than Israel, and we would be right. It is far more dangerous. [emphasis in original]

In 2018, however, I sensed that this nonchalance was increasingly less secure and confident. While Israelis continue to insist on going about their lives as if there was nothing to worry about, and Israel itself remains a relatively safe place, deep down it seemed that they increasingly feel less safe. On every drive, my brother and sister-in-law started out by saying a prayer asking God to protect them, something I do not remember them doing so openly in the past. Moreover, they always kept their car windows closed, fearing rocks being thrown at them. Nor is this an irrational fear. My oldest niece had rocks thrown at her in a public bus on one recent trip, an event that has made her and her husband more reluctant to travel with their young children to many places that I think previously would not have bothered them. It is this fear that also explains why our route to and from the north of Israel weaved around the West Bank, even though there is an excellent and much more direct highway that could have taken us where we wanted to go through the West Bank. Travel on that road is simply considered too dangerous for ordinary Israeli citizens.

I was here for the Bar Mitzvah of my oldest nephew, Noam. He and his parents live in P’nei Kedem, the isolated tiny settlement that I described in detail in my previous Israeli essay. Everyone who drove home from the party Saturday night did so with some fear, as the road was dark and deserted and passed close to two Palestinian villages in the West Bank under the control of the Palestinian Authority. The image on the right shows the turn-off to one of those nearby Palestinian villages, with P’nei Kedem spelled Pene Kedem on the small sign on the left. The line of cars are heading into that village.

Nothing happened to anyone going home that night, but people were nonetheless afraid.

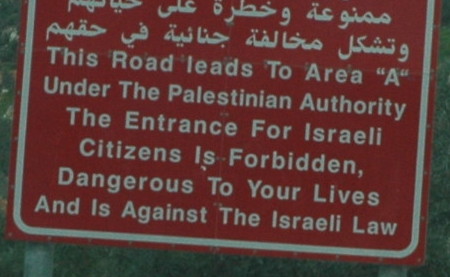

Moreover, the Israeli government is very conscious of this fear, and recognizes that it is justified. In a previous essay I noted how only Israelis are forbidden from entering parts of the West Bank, specifically those areas under the control of the Palestinians, dubbed Areas A and B by the Oslo Accords. Palestinians however can and do go everywhere. Their access to Israeli settlements is not outlawed, and they go there frequently as workers. Thus, there is a form of apartheid in the West Bank, but that apartheid is only applied to Israelis. Only on they are restrictions imposed.

What I hadn’t realized when I wrote that earlier essay is that the restrictions were not imposed by the Palestinians. Instead, it is the Israeli government that has forbidden its own citizens from entering Palestinian controlled areas of the West Bank. The red sign in the image above states this bluntly, according to Israeli law. I have zoomed into the English part of the sign in the image on the left, to make its language easily readable.

Israel has imposed these restrictions because there were too many incidents since the Oslo Accords where innocent Israelis had entered these areas, either by mistake or intentionally, and had gotten attacked, forcing a rescue effort that was expensive and risky for all involved.

It is essential to note that this fear does not exist for the Palestinians. It is also essential to note that the threat of violence is coming almost entirely from the Palestinian side. In their culture, it has somehow become acceptable in the last few decades to violently attack strangers, merely because they happen to belong to another ethnic or religious group. Such behavior is not considered acceptable among Israelis.

In a sense, this is the same thing I have seen on my previous visits. Ordinary people merely want to live their lives, raise their kids and live peaceably with their neighbors, whether they are Jews or Arabs. The wars occur when some people in positions of power lose sight of this fact, and instead pound the table demanding more power and privileges because of the religious, ethnic, or racial group they belong to. In the Middle East today, most of this pounding is being done by the corrupt Palestinian leadership, and its actions are serving to poison their own ordinary people with an unjustified hatred for the ordinary Israelis who are their neighbors.

What I realized after this particular visit, however, is how dire this situation is increasingly becoming. Israel and this tiny area of the Middle East is very crowded, and it is getting even more crowded with each passing year. Unless the Palestinians get some sane leadership soon, willing to accept the reality that the Israelis are there and are not going to go away, we are increasingly faced with a situation that can only lead to horrible violence and massive deaths.

The heart of the problem, as well as the heart of its solution, remains with that Palestinian leadership. Until they give up the fantasy that they can kill all the Jews and return the Middle East to a monolithic Arabic and Islamic culture, we will not have peace in the Middle East. Until they decide to live in peace with the neighbors, we will continue to have ordinary people living in fear as they walk down the street.

It is for this reason that some of Trump’s harsh Middle East policy decisions since taking office might actually lead to some progress. Unlike every past administration since the 1970s, both Democratic and Republican, Trump does not appear to be satisfied with the status quo. He has also made it clear that he is willing to take strong actions against this corrupt Palestinian leadership if they do not change their ways, including cutting them off from the American funding that has allowed them to live well while their people suffer. Hard action against them is necessary, either to force them to change or to force them out. It appears there is a chance that Trump might not be afraid to do this.

Even so, a policy of tough love by Trump might not work. The Arab culture of the Middle East has been seeped with anti-Israel hatred now for decades. It has become deeply ingrained, and merely changing the present leadership is no guarantee that new leaders will be significantly different.

Nonetheless, it would be a good first step. The Palestinians are ordinary people, just like the Israelis. Give them a chance to breathe some fresh air, not tainted by hate, and we might see miracles occur. Such things have happened in the past. They can happen again in the future.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

What’s the attitude among Israelis towards Turkey and

Erdogan?

Do they understand that he is the man who will exterminate all the jews, or do they not understand it, yet? (again)

Localfluff: As with any similar question, it all depends on who you ask. The conservative parties in Israel, from the more secular Likud to the various orthodox religious parties, all understand who Erdogan is. The liberal parties, as in the U.S., tend to live in a fantasy world based on the “Coexist” bumper-sticker.

An understanding, compassionate and practical man that Erdogan.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5435645/Turkish-President-condemned-child-martyrdom-comments.html

Islam understands what the West has long ago forgotten in their Liberal stupor, the leadership anyway. The Progressives will straighten everything out, Progressive leaders like Justin Trudeau (Idiot) will handle everything .

Well, Erdogan is closer to Israel than to any other Western nation, especially now as he is invading Syria to holocaust all kurds. Except for Greece that is on its feet with the highest defense spendings of any NATO member.

What, me worry?

Na, that’s all just nothing to care about.

Cotour, you misspoke about Trudeau; He is not an idiot. Nor was Obama. Both were extremely short sighted and lived in a dream world. However, the harm they did and are doing to the world will be difficult to erase. I have no use for either. Their one world government ideology (if not directly spoken) may result in Israel being the center of a much greater war. Antisemitism is strong with both of those leaders. One, we hope will soon be also an ex-leader.

I would think Israel’s greatest threat is the increased Iranian/Hezbollah presence in Syria and Lebanon. Erdogan imagines himself, like Saddam, as the great Sunni leader/savior or, in this present time of Tsar Putin and Emperor Xi, the new Ottoman Sultan. The Iranian neighbors in Syria will present challenges and dangers for Israel with Turkey looming close by.