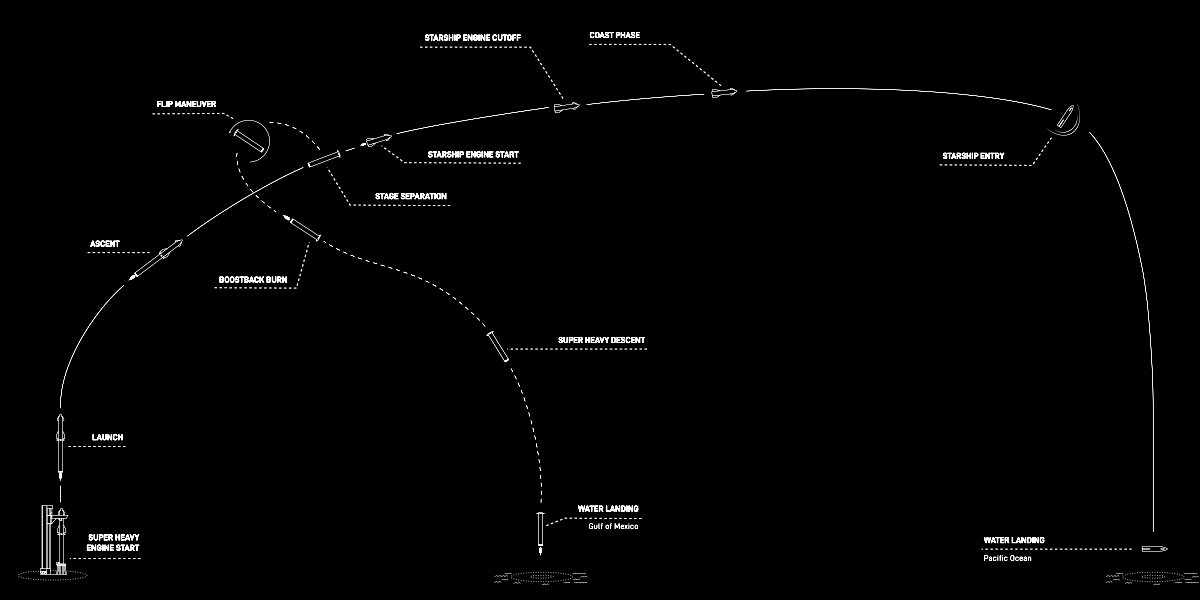

An ordinary person’s view of the Starship/Superheavy countdown

One of my readers, who wishes to go by is nickname Doubting Thomas on Behind the Black, went to Boca Chica earlier this week with the hope of seeing the live first orbital launch of Superheavy with Starship stacked on top. Unfortunately, the launch on April 17, 2023 was scrubbed, and he could not remain in Boca Chica for the now rescheduled launch early tomorrow morning on April 20th.

He sent me some pictures of that experience, however, which I post here with his permission. The best of course is the one to the right, of Starship stacked on Superheavy on the launchpad. This was taken before the roads were closed, and shows how incredibly close the general public can get to that launchpad simply by driving past on a public road.

The next few pictures give us a glimpse at the options people have for viewing future Boca Chica launches.

» Read more

One of my readers, who wishes to go by is nickname Doubting Thomas on Behind the Black, went to Boca Chica earlier this week with the hope of seeing the live first orbital launch of Superheavy with Starship stacked on top. Unfortunately, the launch on April 17, 2023 was scrubbed, and he could not remain in Boca Chica for the now rescheduled launch early tomorrow morning on April 20th.

He sent me some pictures of that experience, however, which I post here with his permission. The best of course is the one to the right, of Starship stacked on Superheavy on the launchpad. This was taken before the roads were closed, and shows how incredibly close the general public can get to that launchpad simply by driving past on a public road.

The next few pictures give us a glimpse at the options people have for viewing future Boca Chica launches.

» Read more