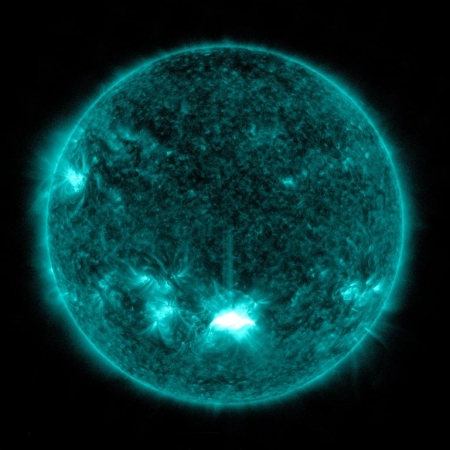

Sunspot update: Sun continues its higher than predicted activity

With the beginning of a new month comes my monthly sunspot update, based on NOAA’s most recent monthly graph of sunspot activity. That graph is below, annotated to show the previous solar cycle predictions and thus provide context. It has now been extended from last month to include the Sun’s sunspot activity in October.

Sunspot activity in October continued to be higher than predicted, though the month saw a slight drop from September. Even so, the number of sunspots seen on the Sun’s facing hemisphere in October were the most since August of 2016, when the Sun was ramping down to solar minimum.

With the beginning of a new month comes my monthly sunspot update, based on NOAA’s most recent monthly graph of sunspot activity. That graph is below, annotated to show the previous solar cycle predictions and thus provide context. It has now been extended from last month to include the Sun’s sunspot activity in October.

Sunspot activity in October continued to be higher than predicted, though the month saw a slight drop from September. Even so, the number of sunspots seen on the Sun’s facing hemisphere in October were the most since August of 2016, when the Sun was ramping down to solar minimum.