NASA announced yesterday that seven countries — the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Japan, Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates and Italy — have now signed the Artemis Accords, the Trump administration’s effort to create a legal framework that will protect property rights in space and get around the legal limitations imposed by the Outer Space Treaty.

I suspect this announcement was in response to statements earlier this week by Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Russia’s space agency, that they will not partner with the U.S. in its Lunar Gateway space station project. Though Rogozin cited other issues for the decision, such at the fact that they would not be treated as an equal partner in Gateway, I suspect the decision was also made because Russia’s government opposes the Artemis Accords and does not wish to sign it. China has said the same.

Since those accords are designed to shift power and control from governments to private enterprise, it is not surprising that Russia and China oppose them. Both are authoritarian top-down societies whose government reflects their culture. To sign an agreement that would take power from the state and give it to their citizens is unacceptable.

So be it. Of the countries that have signed, I expect in future years they will all prosper in space, and eventually force others to accept the ideas of freedom, private property, and capitalism that inspire the accords. Luxombourg is committed to pushing private enterprise and investment in commercial space. The UK, Australia, Canada, and Japan all follow the same principles, and all have robust space industries that should only get stronger.

And the UAE, the new baby on the block, wants to make commercial space a big part of its future. Signing these accords — along with their peace deal with Israel — indicates strongly that they mean business, and that they are trying heartily to separate themselves from the radical Islamic movements that have been poisoning the Arab Middle East for decades.

Moreover, the U.S. is requiring any nation that wishes to participate in its effort to return to the Moon to sign these accords. These nations, and their citizens, will therefore have a chance to contribute to that effort, and likely make a lot of money in the process.

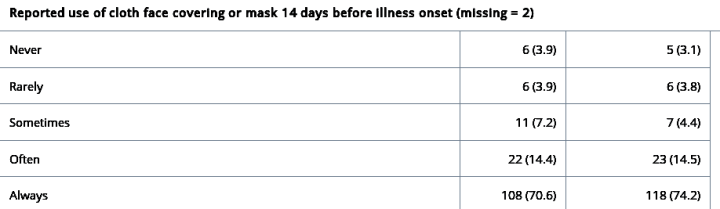

Posting is late today because Diane and I went on an 8-mile hike. My gym now idiotically requires masks while you work out, and I am certainly not going to do that. Therefore, to maintain our cardiovascular systems while strengthening our immune systems (the best defense against all flulike diseases, including the Wuhan virus), we have been doing 6 to 10 mile hikes now twice a week. It means one day a week I need to schedule some posts early, and catch up when I get home. I hope my readers understand.