Engineers set new laser communications record to asteroid probe Psyche

As part of a continuing test program, engineers have set a new long distance laser communications record, exceeding 290 million miles, by successfully using a laser to send communicate with the asteroid probe Psyche from Earth.

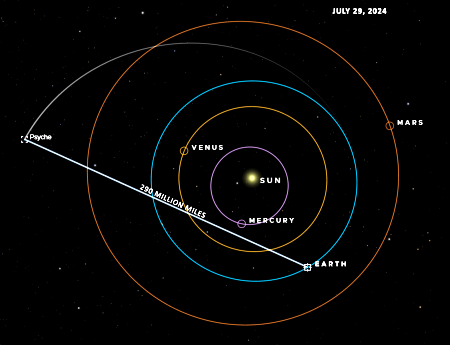

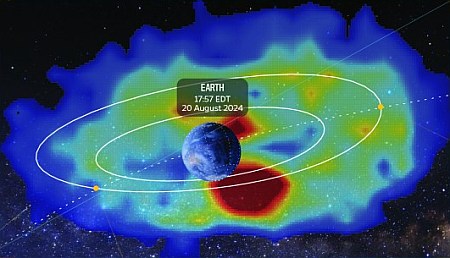

The graph to the right, not to scale, shows the orbital configuation of the laser record. It appears however that little actual data was sent in this last test. It merely demonstrated that a link could be established. An actual data transfer record by laser occurred in June.

On June 24, when Psyche was about 240 million miles (390 million kilometers) from Earth — more than 2½ times the distance between our planet and the Sun — the project achieved a sustained downlink data rate of 6.25 megabits per second, with a maximum rate of 8.3 megabits per second. While this rate is significantly lower than the experiment’s maximum, it is far higher than what a radio frequency communications system using comparable power can achieve over that distance.

The high data rates promised by laser communications will significantly improve deep space operations. Most especially, the ability to get data back in much larger packets more quickly will reduce the antenna bottleneck on Earth that limits the number of missions as well as the data can be returned daily. More missions will be able to fly, and scientists and engineers will get their results faster.

As part of a continuing test program, engineers have set a new long distance laser communications record, exceeding 290 million miles, by successfully using a laser to send communicate with the asteroid probe Psyche from Earth.

The graph to the right, not to scale, shows the orbital configuation of the laser record. It appears however that little actual data was sent in this last test. It merely demonstrated that a link could be established. An actual data transfer record by laser occurred in June.

On June 24, when Psyche was about 240 million miles (390 million kilometers) from Earth — more than 2½ times the distance between our planet and the Sun — the project achieved a sustained downlink data rate of 6.25 megabits per second, with a maximum rate of 8.3 megabits per second. While this rate is significantly lower than the experiment’s maximum, it is far higher than what a radio frequency communications system using comparable power can achieve over that distance.

The high data rates promised by laser communications will significantly improve deep space operations. Most especially, the ability to get data back in much larger packets more quickly will reduce the antenna bottleneck on Earth that limits the number of missions as well as the data can be returned daily. More missions will be able to fly, and scientists and engineers will get their results faster.