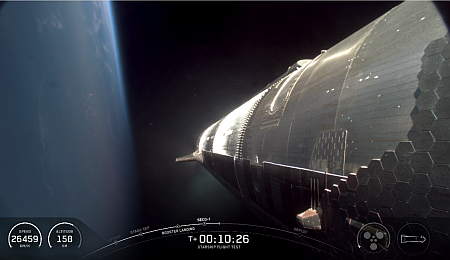

SpaceX launches Starship/Superheavy on ninth test flight, but experiences issues in orbit

Starship in orbit before losing its attitude control

SpaceX today was able to successfully launch Starship and Superheavy on its ninth test flight, lifting off from SpaceX’s Starbase spaceport at Boca Chica.

The Superheavy booster completed its second flight, with one of its Raptor engines actually flying for the third time. Rather than recapture it with the launchpad chopsticks, engineers instead decided to push its re-entry capabilities to their limit. The booster operated successfully until it was to make its landing burn over the Gulf of Mexico, but when the engines ignited all telemetry was lost. Apparently that hard re-entry path was finally too much for the booster.

Starship reached orbit and functioned successfully for the first twenty minutes or so. When engineers attempted a test deployment of some dummy Starlink satellites, the payload door would not open properly. The engineers then closed the door and canceled the deployment.

Subsequently leaks inside the spacecraft with its attitude thrusters caused the attitude system to shut down and Starship started to spin in orbit. At that point the engineers cancelled the Raptor engine relight burn. The spacecraft then descended over the Indian Ocean as planned, but in an uncontrolled manner. Mission control then vented its fuel to reduce its weight and explosive condition. It essentially broke up over the ocean, with data was gathered on the thermal system until all telemetry was lost.

Though overall this was a much more successful flight than the previous two, both of which failed just before or as Starship reached orbit, the test flight once again was unable to do any of its objectives in orbit. It did no deployment test, no orbital Raptor engine burn test, and no the re-entry tests of Starship’s thermal protection system. Obviously the engineers gathered a great deal of data during the flight, but far less than hoped for.

SpaceX has a lot of Superheavy and Starship prototypes sitting in the wings. I expect it will attempt its next flight test, the tenth, relatively quickly, by July at the very latest. I also do not expect the FAA to stand in the way. It will once again accept SpaceX’s investigative conclusions instantly and issue a launch license, when SpaceX stays it is ready to launch.

As Starship reached orbit as planned, I am counting this as a successfully launch. The leaders in the 2025 launch race:

64 SpaceX

30 China

6 Rocket Lab

6 Russia

SpaceX now leads the rest of the world in successful launches, 64 to 49.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

May 27, 2025 Quick space links

Courtesy of BtB’s stringer Jay, who also notes as I do the overall lack of news stories today. As he says, “Everyone is waiting for Starship 9 to launch.”

This post is also an open thread. I welcome my readers to post any comments or additional links relating to any space issues, even if unrelated to the links below.

- Ispace explains why its Resilience lander will set down at Mare Frigoris on the Moon

Landing is still targeting June 5, 2025.

- South Korean rocket startup Innospace delays its first launch from July 2025 to second half of 2025

It appears they discovered issues with a first stage electric pump.

- Astronomers detect a seasonal wobble in Titan’s atmosphere by reviewing Cassini and Huygens archival data

As always there is great uncertainty to these conclusions.

Courtesy of BtB’s stringer Jay, who also notes as I do the overall lack of news stories today. As he says, “Everyone is waiting for Starship 9 to launch.”

This post is also an open thread. I welcome my readers to post any comments or additional links relating to any space issues, even if unrelated to the links below.

- Ispace explains why its Resilience lander will set down at Mare Frigoris on the Moon

Landing is still targeting June 5, 2025.

- South Korean rocket startup Innospace delays its first launch from July 2025 to second half of 2025

It appears they discovered issues with a first stage electric pump.

- Astronomers detect a seasonal wobble in Titan’s atmosphere by reviewing Cassini and Huygens archival data

As always there is great uncertainty to these conclusions.

Supreme Court declines case of blacklisted student who declared “There are only two genders”, proving the large leftist blob is not going away no matter what Trump does

Liam Morrison, wearing the evil shirt that he wore the

second time teachers at Nichols Middle School sent

him home.

The Supreme Court today declined by a vote of 7-2 to hear the case of Liam Morrison, who as a 12-year-old was sent home from Nichols Middle School in Massachusetts because he wore a T-shirt that said “There are only two genders.” Later he came to school wearing the shirt in the picture to the right, and was sent home again.

Morrison and his parents sued, noting in their complaint that since the 1960s the courts have consistently ruled that students have free speech rights. However, in almost all those earlier cases the students were expressing views supportive of leftist causes, so of course their first amendment rights were aggressively protected by the courts.

Because Liam Morrison was taking a conservative rightwing position, however, the court now believes students like him are too young to have first amendment rights, and so of course he has been effectively silenced in school, permanently.

This case illustrates something that all freedom-loving Americans had better recognize. Just because Trump is shutting down whole agencies, firing hundreds of thousands of leftist government workers, denying federal funds to indoctrination universities like Harvard, we should not assume that all will be well in just a few years.

» Read more

Now available in hardback and paperback as well as ebook!

From the press release: In this ground-breaking new history of early America, historian Robert Zimmerman not only exposes the lie behind The New York Times 1619 Project that falsely claims slavery is central to the history of the United States, he also provides profound lessons about the nature of human societies, lessons important for Americans today as well as for all future settlers on Mars and elsewhere in space.

Conscious Choice: The origins of slavery in America and why it matters today and for our future in outer space, is a riveting page-turning story that documents how slavery slowly became pervasive in the southern British colonies of North America, colonies founded by a people and culture that not only did not allow slavery but in every way were hostile to the practice.

Conscious Choice does more however. In telling the tragic history of the Virginia colony and the rise of slavery there, Zimmerman lays out the proper path for creating healthy societies in places like the Moon and Mars.

“Zimmerman’s ground-breaking history provides every future generation the basic framework for establishing new societies on other worlds. We would be wise to heed what he says.” —Robert Zubrin, founder of the Mars Society.

All editions are available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and all book vendors, with the ebook priced at $5.99 before discount. All editions can also be purchased direct from the ebook publisher, ebookit, in which case you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

Autographed printed copies are also available at discount directly from the author (hardback $29.95; paperback $14.95; Shipping cost for either: $6.00). Just send an email to zimmerman @ nasw dot org.

SpaceX launches 24 Starlink satellites

SpaceX today successfully placed another 24 Starlink satellites into orbit, its Falcon 9 rocket lifting off from Vandenberg Space Force base in California.

The first stage completed its thirteenth flight, landing on a drone ship in the Pacific. At least, it appeared so, though there were problems this time with the live stream, which cut off just before touchdown.

The leaders in the 2025 launch race:

63 SpaceX

30 China

6 Rocket Lab

6 Russia

SpaceX now leads the rest of the world in successful launches, 63 to 49.

SpaceX today successfully placed another 24 Starlink satellites into orbit, its Falcon 9 rocket lifting off from Vandenberg Space Force base in California.

The first stage completed its thirteenth flight, landing on a drone ship in the Pacific. At least, it appeared so, though there were problems this time with the live stream, which cut off just before touchdown.

The leaders in the 2025 launch race:

63 SpaceX

30 China

6 Rocket Lab

6 Russia

SpaceX now leads the rest of the world in successful launches, 63 to 49.

The Sun’s surface, in high resolution

Click for movie (though not of this image)

Cool image time! The picture to the right, reduced and sharpened to post here, was one of a number of pictures released today by the science team operating the new adaptive optics at the 60 inch Goode Solar Telescope (GST) at the Big Bear Solar Observatory (BBSO) in California. It shows the fluffy surface of the Sun, made of many needle-like threads called spicules, with larger bits of plasma (in the center) flung upward and back along the Sun’s magnetic field lines.

If you click on the image, you can watch a 42-second movie produced by many images of a different plasma blob as it changes and evolves. Other short movies produced show bits of this material falling back quickly along those field lines as well as that fluffy surface of needles waving almost like tall prairie grass. The width of the image covers approximately 25,000 miles, which means you could fit about three Earth’s in this space.

To create these images from a ground-based telescope required new technology:

The GST system Cona uses a mirror that continuously reshapes itself 2,200 times per second to counteract the image degradation caused by turbulent air. “Adaptive optics is like a pumped-up autofocus and optical image stabilization in your smartphone camera, but correcting for the errors in the atmosphere rather than the user’s shaky hands,” says BBSO Optical Engineer and Chief Observer, Nicolas Gorceix.

Using this refined imagery, solar scientists will be better able to track and observe the Sun’s small scale behavior (actually quite large on human scales).

Click for movie (though not of this image)

Cool image time! The picture to the right, reduced and sharpened to post here, was one of a number of pictures released today by the science team operating the new adaptive optics at the 60 inch Goode Solar Telescope (GST) at the Big Bear Solar Observatory (BBSO) in California. It shows the fluffy surface of the Sun, made of many needle-like threads called spicules, with larger bits of plasma (in the center) flung upward and back along the Sun’s magnetic field lines.

If you click on the image, you can watch a 42-second movie produced by many images of a different plasma blob as it changes and evolves. Other short movies produced show bits of this material falling back quickly along those field lines as well as that fluffy surface of needles waving almost like tall prairie grass. The width of the image covers approximately 25,000 miles, which means you could fit about three Earth’s in this space.

To create these images from a ground-based telescope required new technology:

The GST system Cona uses a mirror that continuously reshapes itself 2,200 times per second to counteract the image degradation caused by turbulent air. “Adaptive optics is like a pumped-up autofocus and optical image stabilization in your smartphone camera, but correcting for the errors in the atmosphere rather than the user’s shaky hands,” says BBSO Optical Engineer and Chief Observer, Nicolas Gorceix.

Using this refined imagery, solar scientists will be better able to track and observe the Sun’s small scale behavior (actually quite large on human scales).

Leaving Earth: Space Stations, Rival Superpowers, and the Quest for Interplanetary Travel, can be purchased as an ebook everywhere for only $3.99 (before discount) at amazon, Barnes & Noble, all ebook vendors, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit.

If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big oppressive tech companies and I get a bigger cut much sooner.

Winner of the 2003 Eugene M. Emme Award of the American Astronautical Society.

"Leaving Earth is one of the best and certainly the most comprehensive summary of our drive into space that I have ever read. It will be invaluable to future scholars because it will tell them how the next chapter of human history opened." -- Arthur C. Clarke

Live stream of Elon Musk’s speech to SpaceX employees today

FINAL UPDATE: It appears his talk has been called off, for the present. I suspect he wants a better idea what happened on today’s flight before speaking.

UPDATE: It appears Musk has rescheduled his speech for 6 pm (Central) tonight, after the launch of the ninth test flight of Starship/Superheavy. The embedded live stream below is for this rescheduled broadcast.

I have embedded below the Space Affairs live stream of Elon Musk’s speech that he plans to give to his SpaceX employees today at 10 am (Pacific) today. Musk has entitled it “The road to making life interplanetary.” He has already indicated that he will outline in more detail SpaceX’s program for getting Starship/Superheavy operational, including the likelihood of test flights to Mars in the near future.

» Read more

FINAL UPDATE: It appears his talk has been called off, for the present. I suspect he wants a better idea what happened on today’s flight before speaking.

UPDATE: It appears Musk has rescheduled his speech for 6 pm (Central) tonight, after the launch of the ninth test flight of Starship/Superheavy. The embedded live stream below is for this rescheduled broadcast.

I have embedded below the Space Affairs live stream of Elon Musk’s speech that he plans to give to his SpaceX employees today at 10 am (Pacific) today. Musk has entitled it “The road to making life interplanetary.” He has already indicated that he will outline in more detail SpaceX’s program for getting Starship/Superheavy operational, including the likelihood of test flights to Mars in the near future.

» Read more

“Was this trip necessary?”

An evening pause: On Memorial Day, let’s revisit an evening pause from 2011 of one short scene from the William Wellman film, Battleground (1949), to remind us why sometimes it is necessary to fight a war.

The saddest thing about this clip is how ugly it makes too many modern Americans look, for they have adopted the certain, ignorant, and bigoted aspects of the totalitarians from the 1930s and 1940s that the generation then fought so hard to defeat. Today’s American totalitarians — almost all of whom are on the left — are certain that because Donald Trump is doing things they disagree with, he along with all of his supporters should be killed. No debate is permitted. They are right and anyone who challenges them is evil.

Memorial Day is not simply about remembering the dead so that they will not have died in vain. It is also about remembering why they died.

The real reason we celebrate Memorial Day

To the right is another cool image, but this one has nothing to do with astronomy, though you will likely be hard pressed to figure out exactly what you are looking at without some study. It is clearly some broken metal object inside a forest, but identifying its exact nature is not obvious.

What you are looking at is the remains of a propeller plane (likely flown on a reconnaissance mission) that crashed in the jungles of Vietnam during that long and tragic war of the 1960s and 1970s. Most amazingly, despite its twisted nature, the pilot survived and was fortunately quickly rescued by American troops before the arrival of the Vietcong.

That pilot’s name was Francis James Floyd. His son Jeffrey, a regular reader of Behind the Black, sent me the picture to illustrate that guys who fly wingsuits are not the only ones willing to do crazy things in the air. As he wrote,

Our dad fought in WWII, Korea and Vietnam as an Air Force pilot. While he had to learn how to parachute jump, he hated it. Even if the engine(s) failed, as long as he had his wings attached, he would not exit (jump). He said “There are two kinds of people that jump out of airplanes: idiots, and people in the armed services.”

So, the attached photo is what was left of his plane in Vietnam. He used the tops of the forest trees to try to slow down, like skimming the water. Fortunately, the good guys reached him first, and he came home.

Francs Floyd however was not an exception or rare thing, like the wingsuit fliers are today. He was one of a massive generation of Americans who, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, quickly enlisted to defend the United States and — more importantly — its fundamental principles of freedom and limited government.

Floyd was only twenty when he enlisted in 1942. He had no flight experience, but was quickly trained to become a pilot who flew fighter bomber missions over Italy. Later he returned to fly in the Korean War, and then again in Vietnam. As his son adds,

» Read more

A galactic pinwheel

It’s cool image time, partly because we have a cool image and partly because there is little news today due to the holiday. The picture to the right, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was taken by the Hubble Space Telescope and was released today as the science team’s picture of the week. It shows us a classic pinwheel galaxy located approximately 46 million light years away. From the caption:

A spiral galaxy seen face-on. Its centre is crossed by a broad bar of light. A glowing spiral arm extends from each end of this bar, both making almost a full turn through the galaxy’s disc before fading out.

The bright object with the four spikes of light is a foreground star inside the Milky Way and only 436 light years away. The bright orange specks inside the spiral arms are likely star forming regions, with the blue indicating gas clouds.

As for the holiday, I’ll have more to say about Memorial Day later today.

It’s cool image time, partly because we have a cool image and partly because there is little news today due to the holiday. The picture to the right, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was taken by the Hubble Space Telescope and was released today as the science team’s picture of the week. It shows us a classic pinwheel galaxy located approximately 46 million light years away. From the caption:

A spiral galaxy seen face-on. Its centre is crossed by a broad bar of light. A glowing spiral arm extends from each end of this bar, both making almost a full turn through the galaxy’s disc before fading out.

The bright object with the four spikes of light is a foreground star inside the Milky Way and only 436 light years away. The bright orange specks inside the spiral arms are likely star forming regions, with the blue indicating gas clouds.

As for the holiday, I’ll have more to say about Memorial Day later today.

Cargo Dragon splashes down and is recovered successfully

A SpaceX cargo Dragon capsule was recovered successfully earlier today after it splashed down off the coast of California.

The spacecraft carried back to Earth about 6,700 pounds of supplies and scientific experiments designed to take advantage of the space station’s microgravity environment after undocking at 12:05 p.m., May 23, from the zenith port of the space station’s Harmony module.

Some of the scientific hardware and samples Dragon will return to Earth include MISSE-20 (Multipurpose International Space Station Experiment), which exposed various materials to space, including radiation shielding and detection materials, solar sails and reflective coatings, ceramic composites for reentry spacecraft studies, and resins for potential use in heat shields. Samples were retrieved on the exterior of the station and can improve knowledge of how these materials respond to ultraviolet radiation, atomic oxygen, charged particles, thermal cycling, and other factors.

Other cargo returned included a robot hand that tested its grasping and handling capabilities in weightlessness, as well as other experiments.

The capsule itself spent three months in orbit after launching at the end of April.

A SpaceX cargo Dragon capsule was recovered successfully earlier today after it splashed down off the coast of California.

The spacecraft carried back to Earth about 6,700 pounds of supplies and scientific experiments designed to take advantage of the space station’s microgravity environment after undocking at 12:05 p.m., May 23, from the zenith port of the space station’s Harmony module.

Some of the scientific hardware and samples Dragon will return to Earth include MISSE-20 (Multipurpose International Space Station Experiment), which exposed various materials to space, including radiation shielding and detection materials, solar sails and reflective coatings, ceramic composites for reentry spacecraft studies, and resins for potential use in heat shields. Samples were retrieved on the exterior of the station and can improve knowledge of how these materials respond to ultraviolet radiation, atomic oxygen, charged particles, thermal cycling, and other factors.

Other cargo returned included a robot hand that tested its grasping and handling capabilities in weightlessness, as well as other experiments.

The capsule itself spent three months in orbit after launching at the end of April.

SpaceX launches more Starlinks

Earlier today SpaceX successfully placed another 23 Starlink satellites into orbit (including 13 with cell-to-satellite capability), its Falcon 9 lifting off from Cape Canaveral in Florida.

The first stage completed its 24th flight, landing on a drone ship in the Atlantic.

The leaders in the 2025 launch race:

62 SpaceX

30 China

6 Rocket Lab

6 Russia

SpaceX now leads the rest of the world in successful launches, 62 to 49. The company also has another Starlink launch planned for tomorrow morning. The launch was scrubbed, rescheduled for May 27th.

Earlier today SpaceX successfully placed another 23 Starlink satellites into orbit (including 13 with cell-to-satellite capability), its Falcon 9 lifting off from Cape Canaveral in Florida.

The first stage completed its 24th flight, landing on a drone ship in the Atlantic.

The leaders in the 2025 launch race:

62 SpaceX

30 China

6 Rocket Lab

6 Russia

SpaceX now leads the rest of the world in successful launches, 62 to 49. The company also has another Starlink launch planned for tomorrow morning. The launch was scrubbed, rescheduled for May 27th.

Orbital tug startup Impulse Space wins contract with satellite company SES

The orbital tug startup Impulse Space has won a contract to use its Helios tug to transport the satellites of the long established Luxembourg company SES to their correct orbit after launch.

The companies announced May 22 that they signed a multi-launch agreement that starts with a mission in 2027 where Impulse’s Helios kick stage, placed into low Earth orbit by a medium-class rocket, will send a four-ton SES satellite from LEO to GEO within eight hours. The announcement did not disclose the vehicle that will launch Helios and the satellite, or the specific SES satellite.

The agreement, the companies said, includes an “opportunity” for additional missions to transport SES satellites to GEO or medium Earth orbits.

This the first satellite tug contract for Impulse’s Helios tug, which is the larger of the company’s two tugs, the smaller version dubbed Mira. While Mira has completed an orbital demo mission, Helios has not yet flown, though it has three planned launches beginning in 2026.

The orbital tug startup Impulse Space has won a contract to use its Helios tug to transport the satellites of the long established Luxembourg company SES to their correct orbit after launch.

The companies announced May 22 that they signed a multi-launch agreement that starts with a mission in 2027 where Impulse’s Helios kick stage, placed into low Earth orbit by a medium-class rocket, will send a four-ton SES satellite from LEO to GEO within eight hours. The announcement did not disclose the vehicle that will launch Helios and the satellite, or the specific SES satellite.

The agreement, the companies said, includes an “opportunity” for additional missions to transport SES satellites to GEO or medium Earth orbits.

This the first satellite tug contract for Impulse’s Helios tug, which is the larger of the company’s two tugs, the smaller version dubbed Mira. While Mira has completed an orbital demo mission, Helios has not yet flown, though it has three planned launches beginning in 2026.

Senate schedules vote for confirming Jared Isaacman as NASA administrator

The Senate is now targeting early June for its vote on Jared Isaacman’s nomination as NASA administrator.

Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-S.D.) filed cloture on Isaacman’s nomination May 22, a procedural move that would set up a vote on the nomination in early June. The Senate is not in session the week of May 26 because of the Memorial Day holiday.

Since his nomination was approved by the Senate Commerce committee in April, Isaacman has been meeting with many other senators. The article at the link does the typical mainstream press thing of pushing back 100% against the proposed NASA cuts put forth by Trump’s 2026 budget proposal, telling us that these senators were generally opposed to those cuts and questioning Isaacman about them, a claim not yet confirmed. It did note something about those senators and those proposed cuts that if true was very startling and possibly very encouraging.

While many of the proposals in the budget, like winding down SLS and Orion, were expected, the scale of the cuts, including a nearly 25% overall reduction in NASA spending, still took many by surprise. [emphasis mine]

In other words, Congress was not surprised by the proposed end of SLS and Orion. It even appears they are ready to give it their stamp of approval.

None of this is confirmed, so take my speculation with a grain of salt. Still, the winds do appear to be blowing against SLS and Orion.

The Senate is now targeting early June for its vote on Jared Isaacman’s nomination as NASA administrator.

Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-S.D.) filed cloture on Isaacman’s nomination May 22, a procedural move that would set up a vote on the nomination in early June. The Senate is not in session the week of May 26 because of the Memorial Day holiday.

Since his nomination was approved by the Senate Commerce committee in April, Isaacman has been meeting with many other senators. The article at the link does the typical mainstream press thing of pushing back 100% against the proposed NASA cuts put forth by Trump’s 2026 budget proposal, telling us that these senators were generally opposed to those cuts and questioning Isaacman about them, a claim not yet confirmed. It did note something about those senators and those proposed cuts that if true was very startling and possibly very encouraging.

While many of the proposals in the budget, like winding down SLS and Orion, were expected, the scale of the cuts, including a nearly 25% overall reduction in NASA spending, still took many by surprise. [emphasis mine]

In other words, Congress was not surprised by the proposed end of SLS and Orion. It even appears they are ready to give it their stamp of approval.

None of this is confirmed, so take my speculation with a grain of salt. Still, the winds do appear to be blowing against SLS and Orion.

Axiom signs deals with Egypt and the Czech Republic

Axiom sent out two press releases yesterday touting separate agreements it has reached with two different countries that will either involve research or a future tourist flight to ISS or to its own station.

First the company announced that it has signed a partnership agreement with the Egyptian Space Agency to partner on a range of space-related research. The language describing this work was typically vague, and is so likely because it depends on the time table for the development and launch of Axiom’s station.

Second Axiom announced that the Czech Republic has signed a letter of intent to fly one of its own astronauts on a future Axiom manned flight. Like the Egyptian press release, view specifics were given, likely for the same reasons.

What both deals signal is that there is an international market for the commercial space stations under development and Axiom is aggressively working to garner that business. Its fourth commercial manned mission, set to launch in early June, carries paid government astronauts from Poland, Hungary, and India. The two new announcements add Egypt and the Czech Republic to the company’s international customers.

Axiom sent out two press releases yesterday touting separate agreements it has reached with two different countries that will either involve research or a future tourist flight to ISS or to its own station.

First the company announced that it has signed a partnership agreement with the Egyptian Space Agency to partner on a range of space-related research. The language describing this work was typically vague, and is so likely because it depends on the time table for the development and launch of Axiom’s station.

Second Axiom announced that the Czech Republic has signed a letter of intent to fly one of its own astronauts on a future Axiom manned flight. Like the Egyptian press release, view specifics were given, likely for the same reasons.

What both deals signal is that there is an international market for the commercial space stations under development and Axiom is aggressively working to garner that business. Its fourth commercial manned mission, set to launch in early June, carries paid government astronauts from Poland, Hungary, and India. The two new announcements add Egypt and the Czech Republic to the company’s international customers.

May 23, 2025 Zimmerman/Batchelor podcast

Embedded below the fold in two parts.

To listen to all of John Batchelor’s podcasts, go here.

» Read more

Embedded below the fold in two parts.

To listen to all of John Batchelor’s podcasts, go here.

» Read more

Johannes – The Most Beautiful Wingsuit Flight I’ve Done

An evening pause: From the peak of the Wetterhorn, 12,106 feet. As always, these videos don’t show the work required to get to that peak, but he does describe it on the youtube page:

We climbed over the Willsgrätli, taking around 4 hours to reach the summit of the Wetterhorn. Holy moly… this climb was serious. We didn’t use ropes, and the heavy backpack caused me some problems in certain climbing sections.

What are you planning to do this Memorial Day weekend?

Hat tip Judd Clark.

SpaceX launches another 27 Starlink satellites

SpaceX today successfully launched another 27 Starlink satellites, its Falcon 9 rocket lifting off from Vandenberg in California.

The first stage completed its 18th flight, landing on a drone ship in the Pacific.

The leaders in the 2025 launch race:

61 SpaceX

30 China

6 Rocket Lab

6 Russia

SpaceX now leads the rest of the world in successful launches, 61 to 49.

SpaceX today successfully launched another 27 Starlink satellites, its Falcon 9 rocket lifting off from Vandenberg in California.

The first stage completed its 18th flight, landing on a drone ship in the Pacific.

The leaders in the 2025 launch race:

61 SpaceX

30 China

6 Rocket Lab

6 Russia

SpaceX now leads the rest of the world in successful launches, 61 to 49.

Boeing and Justice Department reach new deal on criminal prosecution for 737-Max crashes

In order to avoid a criminal trial scheduled for June where Boeing would be on trial for the deaths of 346 people from two 737-Max crashes in 2018 and 2019, the company and the Justice Department have worked out a new plea bargain deal that includes a much larger pay-out to the suing families of the victims.

Under the agreement, Boeing will have to “pay or invest” more than $1.1 billion, the DOJ said in its filing in federal court in Texas on Friday. That amount includes a $487.2 million criminal fine, though $243.6 million it already paid in an earlier agreement would be credited. It also includes $444.5 million for a new fund for crash victims, and $445 million more on compliance, safety and quality programs.

In the filing the Justice Department states it has met with the families to discuss the deal, but it remains unclear whether they will accept it or continue their suit. If the latter it could be that this deal will fail, just as the previous deals in 2021 and 2024. A major sticking point for the families is that Boeing will be allowed to avoid a trial and being convicted for murder and fraud, facts that the company has already admitted to in the previous deals.

In order to avoid a criminal trial scheduled for June where Boeing would be on trial for the deaths of 346 people from two 737-Max crashes in 2018 and 2019, the company and the Justice Department have worked out a new plea bargain deal that includes a much larger pay-out to the suing families of the victims.

Under the agreement, Boeing will have to “pay or invest” more than $1.1 billion, the DOJ said in its filing in federal court in Texas on Friday. That amount includes a $487.2 million criminal fine, though $243.6 million it already paid in an earlier agreement would be credited. It also includes $444.5 million for a new fund for crash victims, and $445 million more on compliance, safety and quality programs.

In the filing the Justice Department states it has met with the families to discuss the deal, but it remains unclear whether they will accept it or continue their suit. If the latter it could be that this deal will fail, just as the previous deals in 2021 and 2024. A major sticking point for the families is that Boeing will be allowed to avoid a trial and being convicted for murder and fraud, facts that the company has already admitted to in the previous deals.

Cargo Dragon undocks from ISS

That this story is not news anymore is really the story. A cargo Dragon capsule that has been docked to ISS since April 22, 2025 today undocked successfully and is scheduled to splashdown off the coast of California on Sunday, May 25, 2025 in the early morning hours.

SpaceX’s Dragon missions to ISS have become so routine that NASA is not even planning to live stream the splashdown, posting updates instead online. This is not actually a surprise, since NASA has practically nothing to do with the splashdown. Once the capsule undocked from ISS, its operation and recovery is entirely in the hands of SpaceX, a private American company.

For NASA, SpaceX is acting as its UPS delivery truck, bringing back to several tons of experiments. And like all UPS delivery trucks, making a delivery is not considered news.

And yet, this is a private commercial spacecraft returning from space, after completing a profitable flight for its owners! That this is now considered so routine that it doesn’t merit much press coverage tells us that the industry of space is beginning to mature into something truly real and sustainable, irrelevant to government.

That this story is not news anymore is really the story. A cargo Dragon capsule that has been docked to ISS since April 22, 2025 today undocked successfully and is scheduled to splashdown off the coast of California on Sunday, May 25, 2025 in the early morning hours.

SpaceX’s Dragon missions to ISS have become so routine that NASA is not even planning to live stream the splashdown, posting updates instead online. This is not actually a surprise, since NASA has practically nothing to do with the splashdown. Once the capsule undocked from ISS, its operation and recovery is entirely in the hands of SpaceX, a private American company.

For NASA, SpaceX is acting as its UPS delivery truck, bringing back to several tons of experiments. And like all UPS delivery trucks, making a delivery is not considered news.

And yet, this is a private commercial spacecraft returning from space, after completing a profitable flight for its owners! That this is now considered so routine that it doesn’t merit much press coverage tells us that the industry of space is beginning to mature into something truly real and sustainable, irrelevant to government.

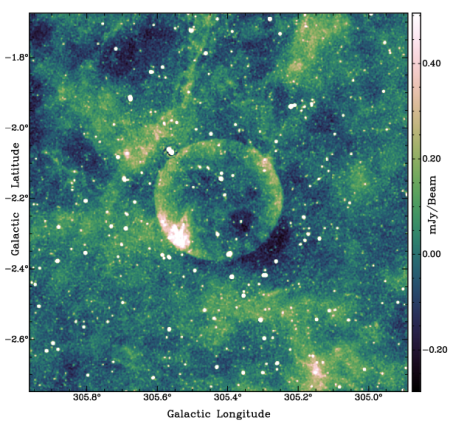

Astronomers discover a perfect sphere in radio

Using the array of radio dishes dubbed the Australian Square Kilometre Array, astronomers have made the serendipitous discovery of what appears to be a perfect sphere of radio emissions tens of light years in diameter and tens of thousands of light years away and near the galactic center.

The scientists have dubbed the object Teleios, Greek for ‘complete’ or ‘perfect’. The image to the right is that radio image. Though the astronomers posit that it must have been formed from a supernova explosion, there are problems with that conclusion. From their paper [pdf]:

Unfortunately, all examined scenarios have their challenges, and no definitive Supernova origin type can be established at this stage. Remarkably, Teleios has retained its symmetrical shape as it aged even to such a diameter, suggesting expansion into a rarefied and isotropic ambient medium. The low radio surface brightness and the lack of pronounced polarisation can be explained by a high level of ambient rotation measure (RM), with the largest RM being observed at Teleios’s centre.

In other words, this object only emits in radio waves, is not visible in optical or other wavelengths as expected, and thus doesn’t really fit with any theories describing the evolution of supernova explosions. Yet its nature fits all other possible known space objects even less, such as planetary nebulae, nova remnants, Wolf-Rayet stars, or even super-bubbles of empty space (such as the Local Bubble the solar system is presently in).

Baffled, the scientists even considered the possibility that they had discovered an artificially built Dyson Sphere, but dismissed that idea because Teleios emits no infrared near its boundaries, as such a sphere is expected to do.

At present the best theory remains a supernova remnant, though this remains a poor solution at best.

Hat tip to reader (and my former editor at UPI) Phil Berardelli.

Using the array of radio dishes dubbed the Australian Square Kilometre Array, astronomers have made the serendipitous discovery of what appears to be a perfect sphere of radio emissions tens of light years in diameter and tens of thousands of light years away and near the galactic center.

The scientists have dubbed the object Teleios, Greek for ‘complete’ or ‘perfect’. The image to the right is that radio image. Though the astronomers posit that it must have been formed from a supernova explosion, there are problems with that conclusion. From their paper [pdf]:

Unfortunately, all examined scenarios have their challenges, and no definitive Supernova origin type can be established at this stage. Remarkably, Teleios has retained its symmetrical shape as it aged even to such a diameter, suggesting expansion into a rarefied and isotropic ambient medium. The low radio surface brightness and the lack of pronounced polarisation can be explained by a high level of ambient rotation measure (RM), with the largest RM being observed at Teleios’s centre.

In other words, this object only emits in radio waves, is not visible in optical or other wavelengths as expected, and thus doesn’t really fit with any theories describing the evolution of supernova explosions. Yet its nature fits all other possible known space objects even less, such as planetary nebulae, nova remnants, Wolf-Rayet stars, or even super-bubbles of empty space (such as the Local Bubble the solar system is presently in).

Baffled, the scientists even considered the possibility that they had discovered an artificially built Dyson Sphere, but dismissed that idea because Teleios emits no infrared near its boundaries, as such a sphere is expected to do.

At present the best theory remains a supernova remnant, though this remains a poor solution at best.

Hat tip to reader (and my former editor at UPI) Phil Berardelli.

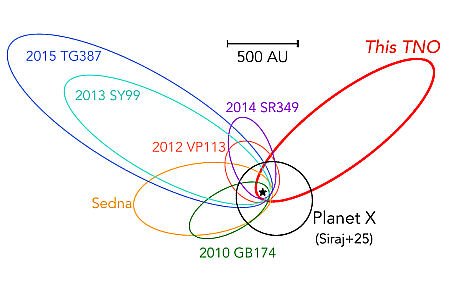

Astronomers discover another object in an orbit so extreme it reaches the outskirts of the theorized Oort Cloud

Astronomers analyzing a dark energy survey by a ground-based telescope have discovered what might be another dwarf planet orbiting the Sun, but doing so in an orbit so extreme that it reaches the outskirts of the theorized Oort Cloud more than 151 billion miles out.

This object, dubbed, 2017 OF201, was found in 19 different observations from 2011 to 2018, allowing the scientists to determine its orbit. The map to the right is figure 2 from their paper [pdf], with the calculated orbit of 2017 OF201 indicated in red. As you can see, this new object — presently estimated to be about 450 miles in diameter — is not the first such object found in the outer solar system with such a wide eccentric orbit. However, the object also travels in a very different region than all those other similar discoveries, suggesting strongly that there are a lot more such objects in the distant outer solar system.

Its existence also contradicts a model that proposed the existence of a larger Planet X. That theory posited that this as-yet undetected Planet X was clustering the orbits of those other distant Trans-Neptunian objects shown on the map.

As shown in Figure 2, the longitude of perihelion of 2017 OF201 lies outside the clustering region near π ≈ 60◦ observed among other extreme TNOs [Trans-Nepturnian Objects]. This distinction raises the question of whether 2017 OF201 is dynamically consistent with the Planet X hypothesis, which suggests that a distant massive planet shepherds TNOs into clustered orbital configurations. Siraj et al. (2025) computed the most probable orbit for a hypothetical Planet X by requiring that it both reproduces the observed clustering in the orbits of extreme TNOs.

…These results suggest that the existence of 2017 OF201 may be difficult to reconcile with this particular instantiation of the Planet X hypothesis. While not definitive, 2017 OF201 provides an additional constraint that complements other challenges to the Planet X scenario, such as observational selection effects and the statistical robustness of the observed clustering.

Planet X might exist, but if so it is likely simple one of many such objects in the outer solar system. It is also likely to be comparable in size to these other objects, which range from Pluto-sized and smaller, making it less unique and less distinct.

In other words, our solar system has almost certainly far more planets than nine (including Pluto).

Hat tip to BtB’s stringer Jay.

Astronomers analyzing a dark energy survey by a ground-based telescope have discovered what might be another dwarf planet orbiting the Sun, but doing so in an orbit so extreme that it reaches the outskirts of the theorized Oort Cloud more than 151 billion miles out.

This object, dubbed, 2017 OF201, was found in 19 different observations from 2011 to 2018, allowing the scientists to determine its orbit. The map to the right is figure 2 from their paper [pdf], with the calculated orbit of 2017 OF201 indicated in red. As you can see, this new object — presently estimated to be about 450 miles in diameter — is not the first such object found in the outer solar system with such a wide eccentric orbit. However, the object also travels in a very different region than all those other similar discoveries, suggesting strongly that there are a lot more such objects in the distant outer solar system.

Its existence also contradicts a model that proposed the existence of a larger Planet X. That theory posited that this as-yet undetected Planet X was clustering the orbits of those other distant Trans-Neptunian objects shown on the map.

As shown in Figure 2, the longitude of perihelion of 2017 OF201 lies outside the clustering region near π ≈ 60◦ observed among other extreme TNOs [Trans-Nepturnian Objects]. This distinction raises the question of whether 2017 OF201 is dynamically consistent with the Planet X hypothesis, which suggests that a distant massive planet shepherds TNOs into clustered orbital configurations. Siraj et al. (2025) computed the most probable orbit for a hypothetical Planet X by requiring that it both reproduces the observed clustering in the orbits of extreme TNOs.

…These results suggest that the existence of 2017 OF201 may be difficult to reconcile with this particular instantiation of the Planet X hypothesis. While not definitive, 2017 OF201 provides an additional constraint that complements other challenges to the Planet X scenario, such as observational selection effects and the statistical robustness of the observed clustering.

Planet X might exist, but if so it is likely simple one of many such objects in the outer solar system. It is also likely to be comparable in size to these other objects, which range from Pluto-sized and smaller, making it less unique and less distinct.

In other words, our solar system has almost certainly far more planets than nine (including Pluto).

Hat tip to BtB’s stringer Jay.

Dawn Aerospace begins offering its suborbital spaceplane to customers

Though the company has only so far flown a small prototype on low altitude supersonic test flights, the spaceplane startup Dawn Aerospace is now taking orders for those who wish to put payloads on its proposed Aurora suborbital spaceplane, targeting a first flight in late 2026.

Dawn Aerospace is taking orders now for the Aurora spaceplane for deliveries starting in 2027. The company has not disclosed pricing for the vehicle, and [CEA Stefan] Powell suggested the company would tailor pricing to each customer. He said that the company estimates, based on market research, that a per-flight price of $100,000 is “absolutely tenable,” and the price could go higher for missions with more customized flight needs. He projects Aurora could fly 100 times a year and has a design life of 1,000 flights, with a total revenue per vehicle of about $100 million.

Though the company had originally touted itself as developing an orbital spaceplane, it recently shifted its goals, at least for the present, to building a very powerful jet comparable in some ways to the X-15, capable of reaching altitudes exceeding 50 miles for short periods and short periods of weightlessness. This capability has some value, and Dawn Aerospace has decided to market it for profit, rather than wait for the orbital version that might be years away.

Though the company has only so far flown a small prototype on low altitude supersonic test flights, the spaceplane startup Dawn Aerospace is now taking orders for those who wish to put payloads on its proposed Aurora suborbital spaceplane, targeting a first flight in late 2026.

Dawn Aerospace is taking orders now for the Aurora spaceplane for deliveries starting in 2027. The company has not disclosed pricing for the vehicle, and [CEA Stefan] Powell suggested the company would tailor pricing to each customer. He said that the company estimates, based on market research, that a per-flight price of $100,000 is “absolutely tenable,” and the price could go higher for missions with more customized flight needs. He projects Aurora could fly 100 times a year and has a design life of 1,000 flights, with a total revenue per vehicle of about $100 million.

Though the company had originally touted itself as developing an orbital spaceplane, it recently shifted its goals, at least for the present, to building a very powerful jet comparable in some ways to the X-15, capable of reaching altitudes exceeding 50 miles for short periods and short periods of weightlessness. This capability has some value, and Dawn Aerospace has decided to market it for profit, rather than wait for the orbital version that might be years away.

NASA continues to push Biden-era interpretation of Artemis Accords

In a press release today describing another international workshop for the signatories of the Artemis Accords in Abu Dhabi this week, NASA continued to put forth the Biden-era interpretation of the Artemis Accords that is diametrically opposed to the original concept of the accords as conceived during the first Trump administration.

The key words are highlighted in quotes below.

The Artemis Accords are a set of non-binding principles signed by nations for a peaceful and prosperous future in space for all of humanity to enjoy. In October 2020, under the first Trump administration, the accords were created, and since then, 54 countries have joined with the United States in committing to transparent and responsible behavior in space.

“Following President Trump’s visit to the Middle East, the United States built upon the successful trip through engagement with a global coalition of nations to further implement the accords – practical guidelines for ensuring transparency, peaceful cooperation, and shared prosperity in space exploration,” said acting NASA Administrator Janet Petro. “These accords represent a vital step toward uniting the world in the pursuit of exploration and scientific discovery beyond Earth. NASA is proud to lead in the overall accords effort, advancing the principles as we push the boundaries of human presence in space – for the benefit of all.”

…participants reaffirmed their commitment to upholding the principles outlined in the accords and to continue identifying best practices and guidelines for safe and sustainable exploration.

…The Artemis Accords are grounded in the Outer Space Treaty and other agreements, including the Registration Convention and the Rescue and Return Agreement, as well as best practices for responsible behavior that NASA and its partners have supported, including the public release of scientific data.

Many of the highlighted phrases are of course quite laudable, such as the desire for peace and the use of space for the benefit of all. The tone and spin however is very globalist and communist, and leaves out entirely the primary reason Trump created the accords in the first place, to encourage private ownership, capitalism, competition, and freedom in space by bypassing or canceling the Outer Space Treaty’s rules that forbid such things.

According to the release there will be more talks among accord signatories in the upcoming September meeting of the International Astronautical Congress. I highlight this press release and its Biden-era language in an effort to make the Trump administration aware that — at least in space — Biden’s policies apparently remain in charge. While I also know this is not the most important priority for Trump, it is also something he does care about, and these issues are critical for the future lives of those who will soon explore and settle the solar system.

Someone in the Trump administration has got shift NASA back to pushing for private enterprise internationally, rather than the feel-good, empty, and communist agenda of the globalist crowd, as illustrated by the language above. And they need to do it before, or even very publicly at that September International Astronautical Congress.

In a press release today describing another international workshop for the signatories of the Artemis Accords in Abu Dhabi this week, NASA continued to put forth the Biden-era interpretation of the Artemis Accords that is diametrically opposed to the original concept of the accords as conceived during the first Trump administration.

The key words are highlighted in quotes below.

The Artemis Accords are a set of non-binding principles signed by nations for a peaceful and prosperous future in space for all of humanity to enjoy. In October 2020, under the first Trump administration, the accords were created, and since then, 54 countries have joined with the United States in committing to transparent and responsible behavior in space.

“Following President Trump’s visit to the Middle East, the United States built upon the successful trip through engagement with a global coalition of nations to further implement the accords – practical guidelines for ensuring transparency, peaceful cooperation, and shared prosperity in space exploration,” said acting NASA Administrator Janet Petro. “These accords represent a vital step toward uniting the world in the pursuit of exploration and scientific discovery beyond Earth. NASA is proud to lead in the overall accords effort, advancing the principles as we push the boundaries of human presence in space – for the benefit of all.”

…participants reaffirmed their commitment to upholding the principles outlined in the accords and to continue identifying best practices and guidelines for safe and sustainable exploration.

…The Artemis Accords are grounded in the Outer Space Treaty and other agreements, including the Registration Convention and the Rescue and Return Agreement, as well as best practices for responsible behavior that NASA and its partners have supported, including the public release of scientific data.

Many of the highlighted phrases are of course quite laudable, such as the desire for peace and the use of space for the benefit of all. The tone and spin however is very globalist and communist, and leaves out entirely the primary reason Trump created the accords in the first place, to encourage private ownership, capitalism, competition, and freedom in space by bypassing or canceling the Outer Space Treaty’s rules that forbid such things.

According to the release there will be more talks among accord signatories in the upcoming September meeting of the International Astronautical Congress. I highlight this press release and its Biden-era language in an effort to make the Trump administration aware that — at least in space — Biden’s policies apparently remain in charge. While I also know this is not the most important priority for Trump, it is also something he does care about, and these issues are critical for the future lives of those who will soon explore and settle the solar system.

Someone in the Trump administration has got shift NASA back to pushing for private enterprise internationally, rather than the feel-good, empty, and communist agenda of the globalist crowd, as illustrated by the language above. And they need to do it before, or even very publicly at that September International Astronautical Congress.

Pentagon official blasts ULA’s slow Vulcan launch pace to Congress

In written testimony to Congress submitted on May 14, 2025, the acting assistant secretary of the Air Force for Space Acquisition and Integration, Major General Stephen Purdy, blasted ULA’s very slow effort to get its new Vulcan rocket operational, causing launch delays for four different military payloads.

“The ULA Vulcan program has performed unsatisfactorily this past year,” Purdy said in written testimony during a May 14 hearing before the House Armed Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Strategic Forces. This portion of his testimony did not come up during the hearing, and it has not been reported publicly to date. “Major issues with the Vulcan have overshadowed its successful certification resulting in delays to the launch of four national security missions,” Purdy wrote. “Despite the retirement of highly successful Atlas and Delta launch vehicles, the transition to Vulcan has been slow and continues to impact the completion of Space Force mission objectives.”

The full written testimony [pdf] is worth reading, because Purdy outlines in great detail the Pentagon’s now full acceptance of the capitalism model. It appears to be trying in all cases to streamline and simplify its contracting system so as to more quickly issue contracts to startups, which were not interested previously in working with the military because they could not afford the long delays between proposal acceptance and the first payments.

In the last decade it appears this process is having some success, resulting for example in the space field the launch of multiple hypersonic tests by a variety of rocket startups. Purdy’s written testimony outlines numerous other examples.

In written testimony to Congress submitted on May 14, 2025, the acting assistant secretary of the Air Force for Space Acquisition and Integration, Major General Stephen Purdy, blasted ULA’s very slow effort to get its new Vulcan rocket operational, causing launch delays for four different military payloads.

“The ULA Vulcan program has performed unsatisfactorily this past year,” Purdy said in written testimony during a May 14 hearing before the House Armed Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Strategic Forces. This portion of his testimony did not come up during the hearing, and it has not been reported publicly to date. “Major issues with the Vulcan have overshadowed its successful certification resulting in delays to the launch of four national security missions,” Purdy wrote. “Despite the retirement of highly successful Atlas and Delta launch vehicles, the transition to Vulcan has been slow and continues to impact the completion of Space Force mission objectives.”

The full written testimony [pdf] is worth reading, because Purdy outlines in great detail the Pentagon’s now full acceptance of the capitalism model. It appears to be trying in all cases to streamline and simplify its contracting system so as to more quickly issue contracts to startups, which were not interested previously in working with the military because they could not afford the long delays between proposal acceptance and the first payments.

In the last decade it appears this process is having some success, resulting for example in the space field the launch of multiple hypersonic tests by a variety of rocket startups. Purdy’s written testimony outlines numerous other examples.

Russia launches classified satellite

Russia today successfully placed a classified military satellite into orbit, its Soyuz-2 rocket lifting off from its Plesetsk spaceport in northeast Russia.

The Russians provided extensive information about the places where the rocket’s lower stages and strap-on boosters would crash, issuing “warnings for the planned rocket boosters impacts between Yar Sale and Ports Yakha settlements, as well as in Panaevsk and Khadyta-Yakha sites.” These crash zones have been used previously. Though unlike China Russia routinely warns its people about such things, like China it has never had a problem dumping these stages on their head.

The leaders in the 2025 launch race:

60 SpaceX

30 China

6 Rocket Lab

6 Russia

SpaceX still leads the rest of the world in successful launches, 60 to 49.

It is entertaining to see that the private American rocket company Rocket Lab is matching Russia launch for launch this year. Once Russia launched dozens of times per year. Now it will do well to achieve one launch per month. Rocket Lab meanwhile is trying to top twenty launches in 2025. It might not meet that number, but it is quite likely to top Russia when the year ends.

Russia today successfully placed a classified military satellite into orbit, its Soyuz-2 rocket lifting off from its Plesetsk spaceport in northeast Russia.

The Russians provided extensive information about the places where the rocket’s lower stages and strap-on boosters would crash, issuing “warnings for the planned rocket boosters impacts between Yar Sale and Ports Yakha settlements, as well as in Panaevsk and Khadyta-Yakha sites.” These crash zones have been used previously. Though unlike China Russia routinely warns its people about such things, like China it has never had a problem dumping these stages on their head.

The leaders in the 2025 launch race:

60 SpaceX

30 China

6 Rocket Lab

6 Russia

SpaceX still leads the rest of the world in successful launches, 60 to 49.

It is entertaining to see that the private American rocket company Rocket Lab is matching Russia launch for launch this year. Once Russia launched dozens of times per year. Now it will do well to achieve one launch per month. Rocket Lab meanwhile is trying to top twenty launches in 2025. It might not meet that number, but it is quite likely to top Russia when the year ends.

SpaceX confirms 9th test flight of Starship/Superheavy now scheduled for May 27, 2025

Starship/Superheavy on March 6, 2025 at T-41 seconds

SpaceX has now confirmed May 27, 2025 as the launch date for the ninth test flight of Starship/Superheavy out of its Starbase spaceport at Boca Chica.

The launch window opens at 6:30 pm (Central), with the live stream beginning 30 minutes earlier. The flight will attempt to refly the Superheavy booster used on flight seven. To push the booster’s limits, it will test “off-nominal scenarios” upon return, requiring for safety that it land in the Gulf of Mexico and not be recaptured by the chopsticks. (Just as I don’t change names or my language willy-nilly because leftists demand it, I won’t play Trump’s name-changing game here. The Gulf of Mexico was given that name more than two centuries ago, most likely by the early Spanish explorers, and that name has been good enough since.)

Starship meanwhile attempt the same test profile planned for the previous two flights but stymied by the failure of the spacecraft before reaching orbit. It will test a Starlink satellite deployment system, do a relight of one of its Raptor engines, and test its thermal ability to survive re-entry.

The company also released a report describing the results of its investigation into the previous launch failure on March 6, 2025.

» Read more

Starship/Superheavy on March 6, 2025 at T-41 seconds

SpaceX has now confirmed May 27, 2025 as the launch date for the ninth test flight of Starship/Superheavy out of its Starbase spaceport at Boca Chica.

The launch window opens at 6:30 pm (Central), with the live stream beginning 30 minutes earlier. The flight will attempt to refly the Superheavy booster used on flight seven. To push the booster’s limits, it will test “off-nominal scenarios” upon return, requiring for safety that it land in the Gulf of Mexico and not be recaptured by the chopsticks. (Just as I don’t change names or my language willy-nilly because leftists demand it, I won’t play Trump’s name-changing game here. The Gulf of Mexico was given that name more than two centuries ago, most likely by the early Spanish explorers, and that name has been good enough since.)

Starship meanwhile attempt the same test profile planned for the previous two flights but stymied by the failure of the spacecraft before reaching orbit. It will test a Starlink satellite deployment system, do a relight of one of its Raptor engines, and test its thermal ability to survive re-entry.

The company also released a report describing the results of its investigation into the previous launch failure on March 6, 2025.

» Read more

Firefall – Just Remember I love You

May 22, 2025 Quick space links

Courtesy of BtB’s stringer Jay. This post is also an open thread. I welcome my readers to post any comments or additional links relating to any space issues, even if unrelated to the links below.

- Blue Origin touts underwater tests of its manned lunar lander design

Essentially divers tested the ladder and hatch design for getting astronauts and cargo in and out of the lander.

- Ispace reports Resilience is continuing to operate as planned in lunar orbit

The landing is still planned for June 5, 2025.

- The UAE hires Firefly’s Blue Ghost to land its Rashid-2 rover on the far side of the Moon

UAE’s first Rashid rover had been carried by Ispace’s first lunar lander, Hakuto-R1, which crashed. It appears the UAE chose Firefly this time after its successful landing of Blue Ghost earlier this year.

- Chinese astronauts on Tiangong-3 complete their first spacewalk

They installed “a debris protection device at its designated location.” It appears they are testing this shield’s effectiveness against micrometeorites and space junk at various locations on the station.

- On this day in 1969 Apollo 10 descended to within nine miles of the lunar surface, testing both the Apollo capsule and Lunar Module in lunar orbit

This was a complete dress rehearsal prior to the Apollo 11 landing two months later. It accomplished everything but the landing itself.

Courtesy of BtB’s stringer Jay. This post is also an open thread. I welcome my readers to post any comments or additional links relating to any space issues, even if unrelated to the links below.

- Blue Origin touts underwater tests of its manned lunar lander design

Essentially divers tested the ladder and hatch design for getting astronauts and cargo in and out of the lander.

- Ispace reports Resilience is continuing to operate as planned in lunar orbit

The landing is still planned for June 5, 2025.

- The UAE hires Firefly’s Blue Ghost to land its Rashid-2 rover on the far side of the Moon

UAE’s first Rashid rover had been carried by Ispace’s first lunar lander, Hakuto-R1, which crashed. It appears the UAE chose Firefly this time after its successful landing of Blue Ghost earlier this year.

- Chinese astronauts on Tiangong-3 complete their first spacewalk

They installed “a debris protection device at its designated location.” It appears they are testing this shield’s effectiveness against micrometeorites and space junk at various locations on the station.

- On this day in 1969 Apollo 10 descended to within nine miles of the lunar surface, testing both the Apollo capsule and Lunar Module in lunar orbit

This was a complete dress rehearsal prior to the Apollo 11 landing two months later. It accomplished everything but the landing itself.

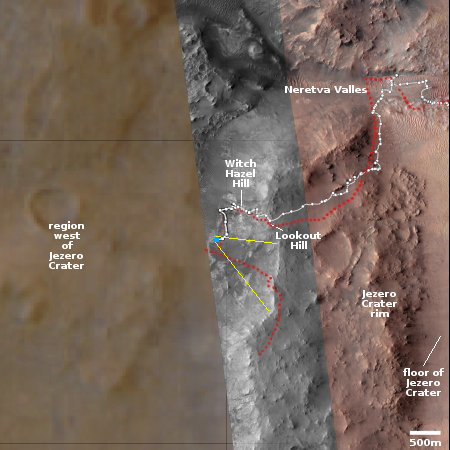

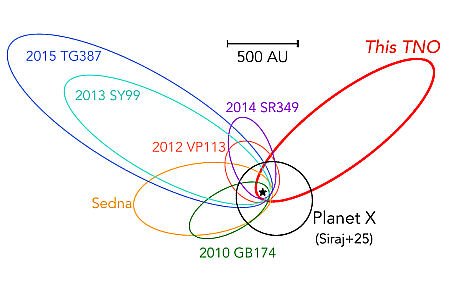

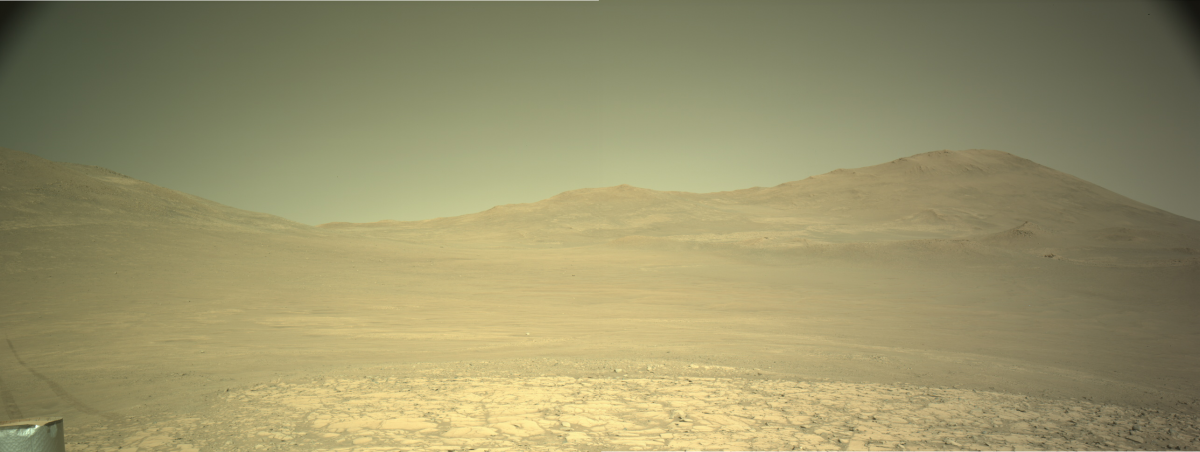

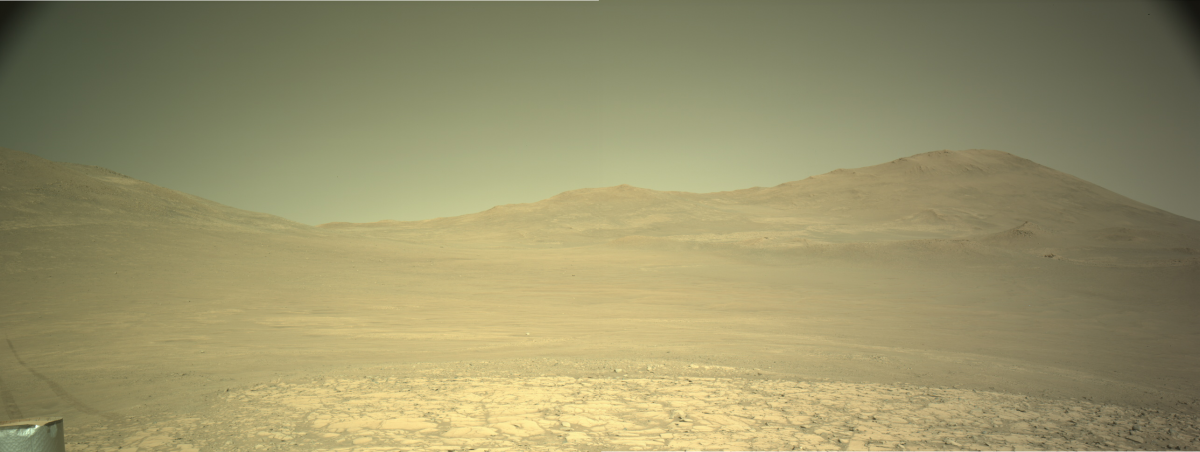

Perseverance moves across the barren outer rim of Jezero Crater

Click for full resolution. For original images go here and here.

Cool image time! While most of the mainstream press will be focusing today on the 360 degree selfie that the Perseverance science team released yesterday, I found the more natural view created above by two pictures taken by the rover’s right navigation camera today (here and here) to be more immediately informative, as well as more evocative.

After spending several months collecting data at a location dubbed Witch Hazel Hill on the outer slopes of the rim of Jezero Crater, the science team has finally had the rover move south along its planned route. The overview map to the right provides the contest. The blue dot marks Perseverance’s present location, the red dotted line its planned route, and the white dotted line its actual travels. The yellow lines mark what I think is the approximate area viewed in the panorama above.

That panorama once again illustrates the stark alienness of Mars. It also shows the startling contrast between the rocky terrain that the rover Curiosity is seeing as it climbs Mount Sharp versus this somewhat featureless terrain traveled so far by Perseverance. Though Perseverance is exploring the ejecta blanket thrown out when the impact occurred that formed Jezero Crater, that event occurred so long ago that subsequent geological processes along with the red planet’s thin atmosphere have been able to smooth this terrain into the barren landscape we now see.

And barren it truly is. There is practically no place on Earth where you could find the surface so completely devoid of life.

Some would view this as a reason not to go to Mars. I see it as the very reason to go, to make this terrain bloom with life, using our fundamental human ability to manufacture tools to adapt the environment to our needs.

Meanwhile, the science team operating Perseverance plans to do more drilling, as this ejecta blanket probably contains material thrown out from the impact that is likely quite old and thus capable of telling us a great deal about far past of Mars’ geological history.

Click for full resolution. For original images go here and here.

Cool image time! While most of the mainstream press will be focusing today on the 360 degree selfie that the Perseverance science team released yesterday, I found the more natural view created above by two pictures taken by the rover’s right navigation camera today (here and here) to be more immediately informative, as well as more evocative.

After spending several months collecting data at a location dubbed Witch Hazel Hill on the outer slopes of the rim of Jezero Crater, the science team has finally had the rover move south along its planned route. The overview map to the right provides the contest. The blue dot marks Perseverance’s present location, the red dotted line its planned route, and the white dotted line its actual travels. The yellow lines mark what I think is the approximate area viewed in the panorama above.

That panorama once again illustrates the stark alienness of Mars. It also shows the startling contrast between the rocky terrain that the rover Curiosity is seeing as it climbs Mount Sharp versus this somewhat featureless terrain traveled so far by Perseverance. Though Perseverance is exploring the ejecta blanket thrown out when the impact occurred that formed Jezero Crater, that event occurred so long ago that subsequent geological processes along with the red planet’s thin atmosphere have been able to smooth this terrain into the barren landscape we now see.

And barren it truly is. There is practically no place on Earth where you could find the surface so completely devoid of life.

Some would view this as a reason not to go to Mars. I see it as the very reason to go, to make this terrain bloom with life, using our fundamental human ability to manufacture tools to adapt the environment to our needs.

Meanwhile, the science team operating Perseverance plans to do more drilling, as this ejecta blanket probably contains material thrown out from the impact that is likely quite old and thus capable of telling us a great deal about far past of Mars’ geological history.