New Webb data says asteroid 2024 YR4 will miss the Moon in 2032

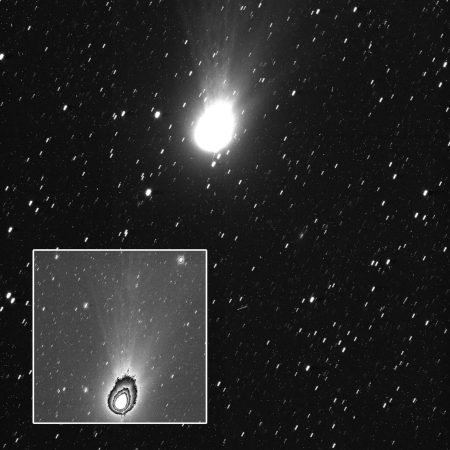

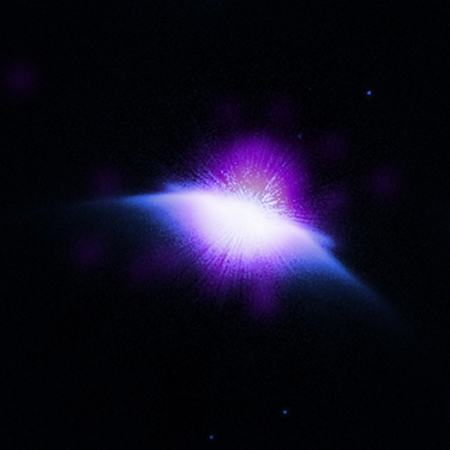

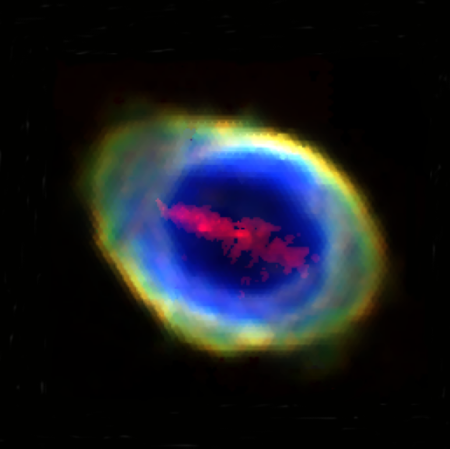

Asteroid 2024 YR4 as seen by Webb in the

mid-infrared in April 2025. Click for original image.

New Webb data collected in February has now eliminated any chance the potentially dangerous asteroid 2024 YR4 will hit either the Earth or the Moon when it makes its next close pass on December 22, 2032.

Using data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope observations collected on Feb. 18 and 26, experts from NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies at the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California have refined near-Earth asteroid 2024 YR4’s orbit and are ruling out a chance of lunar impact on Dec. 22, 2032. With the new data, 2024 YR4 is expected to pass by the lunar surface at a distance of 13,200 miles (21,200 km).

Earlier less precise data had suggested 2024 YR4 had a 4.3% chance of hitting the Moon in 2032. That chance is now zero. This result is actually disappointing, in that an impact of this asteroid, estimated to be about 200 feet in diameter, would have not only been spectacular, but would have been scientifically useful. We would have been able to observe it closely with many ground- and space-based telescopes, and garnered a lot of useful information about the asteroid, the Moon, and the very nature of impacts.

The impact would have also eliminated the chance this asteroid might hit the Earth in the future. 2024 YR4 orbits the Sun about every four years. Previous calculations suggested another potentially dangerous fly-by of Earth in 2047, but these numbers are unreliable because the orbit will be changed by the 2032 fly-by in ways that cannot be predicted as yet.

Asteroid 2024 YR4 as seen by Webb in the

mid-infrared in April 2025. Click for original image.

New Webb data collected in February has now eliminated any chance the potentially dangerous asteroid 2024 YR4 will hit either the Earth or the Moon when it makes its next close pass on December 22, 2032.

Using data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope observations collected on Feb. 18 and 26, experts from NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies at the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California have refined near-Earth asteroid 2024 YR4’s orbit and are ruling out a chance of lunar impact on Dec. 22, 2032. With the new data, 2024 YR4 is expected to pass by the lunar surface at a distance of 13,200 miles (21,200 km).

Earlier less precise data had suggested 2024 YR4 had a 4.3% chance of hitting the Moon in 2032. That chance is now zero. This result is actually disappointing, in that an impact of this asteroid, estimated to be about 200 feet in diameter, would have not only been spectacular, but would have been scientifically useful. We would have been able to observe it closely with many ground- and space-based telescopes, and garnered a lot of useful information about the asteroid, the Moon, and the very nature of impacts.

The impact would have also eliminated the chance this asteroid might hit the Earth in the future. 2024 YR4 orbits the Sun about every four years. Previous calculations suggested another potentially dangerous fly-by of Earth in 2047, but these numbers are unreliable because the orbit will be changed by the 2032 fly-by in ways that cannot be predicted as yet.