Today’s blacklisted American: controversial Nick Fuentes

Banned by the Biden administration

Blacklists are back and the Dems’ have got ’em: Routinely called a racist, bigot, white supremacist, and (of course) an alt-right conservative by the mainstream press, controversial Nick Fuentes’ track record is far from that straight-forward. Though it appears he has often taken some ugly positions and made some even more ugly statements, he apparently has never done anything illegal or outright bigoted.

No matter to the Biden administration and the TSA. They have blacklisted him, banning him from flying on any American airline.

Moreover, the federal government is not the only one blacklisting Fuentes because they don’t like his opinions. As Fuentes himself noted in a April 27th tweet:

Since attending President Trump’s rally on the Ellipse on January 6th I’ve been:

-Banned from AirBnB, Facebook, Instagram, DLive, and Coinbase

-Banned from every payment processor

-Had a bank account frozen

-Put on the no-fly list

And I haven’t even done anything wrong!

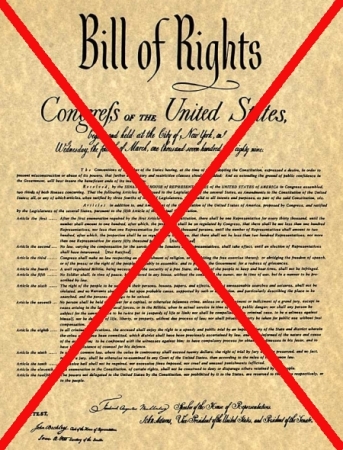

The most important line in his tweet is the last one. What he has said might be wrong-headed, bigoted, or stupid, but in a free country that defends its first amendment, he would be within his rights to say it, and would have broken no laws by doing so.

We no longer live in that long gone free nation. Now we live in a place that routinely uses power to squash radical positions, except when those opinions happen to be leftist radical positions. Those Marxist opinions are always blessed with immunity, no matter how bigoted or vile. In fact, if you dare to criticize the dominant Marxist and bigoted culture in any way at all, you are guaranteed to be called a bigot and are likely to be blacklisted, like Fuentes, for doing so.

Banned by the Biden administration

Blacklists are back and the Dems’ have got ’em: Routinely called a racist, bigot, white supremacist, and (of course) an alt-right conservative by the mainstream press, controversial Nick Fuentes’ track record is far from that straight-forward. Though it appears he has often taken some ugly positions and made some even more ugly statements, he apparently has never done anything illegal or outright bigoted.

No matter to the Biden administration and the TSA. They have blacklisted him, banning him from flying on any American airline.

Moreover, the federal government is not the only one blacklisting Fuentes because they don’t like his opinions. As Fuentes himself noted in a April 27th tweet:

Since attending President Trump’s rally on the Ellipse on January 6th I’ve been:

-Banned from AirBnB, Facebook, Instagram, DLive, and Coinbase

-Banned from every payment processor

-Had a bank account frozen

-Put on the no-fly listAnd I haven’t even done anything wrong!

The most important line in his tweet is the last one. What he has said might be wrong-headed, bigoted, or stupid, but in a free country that defends its first amendment, he would be within his rights to say it, and would have broken no laws by doing so.

We no longer live in that long gone free nation. Now we live in a place that routinely uses power to squash radical positions, except when those opinions happen to be leftist radical positions. Those Marxist opinions are always blessed with immunity, no matter how bigoted or vile. In fact, if you dare to criticize the dominant Marxist and bigoted culture in any way at all, you are guaranteed to be called a bigot and are likely to be blacklisted, like Fuentes, for doing so.