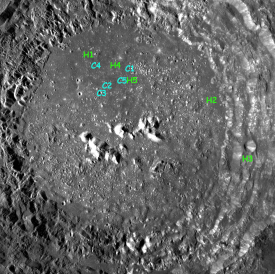

LRO pinpoints Chang’e-4 landing site

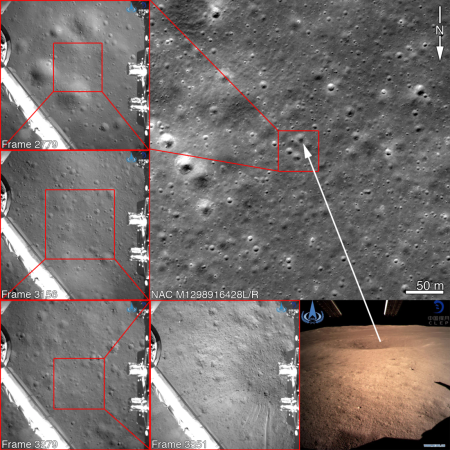

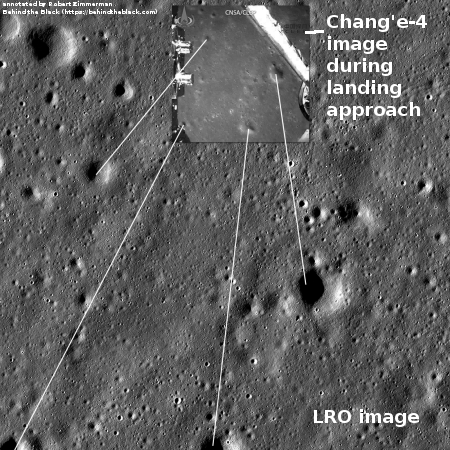

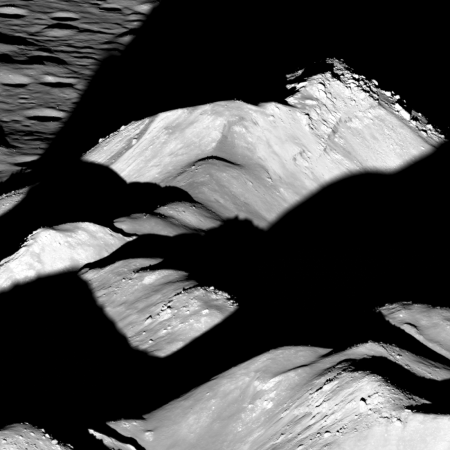

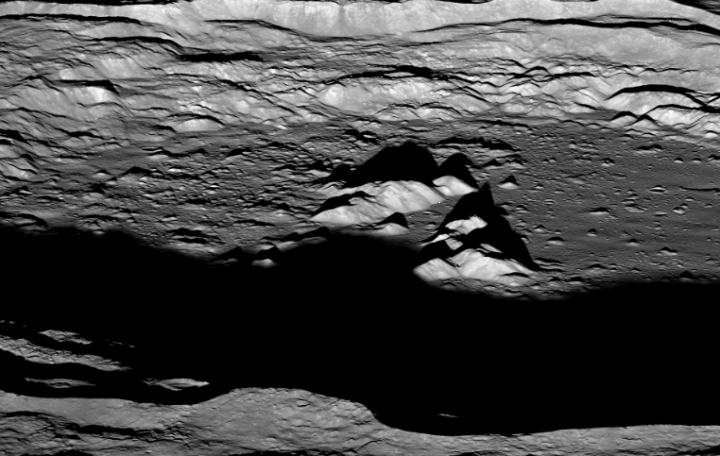

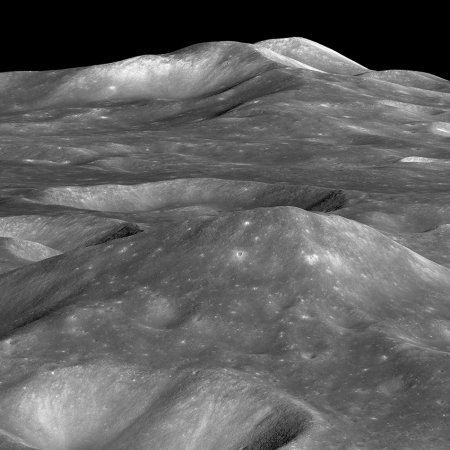

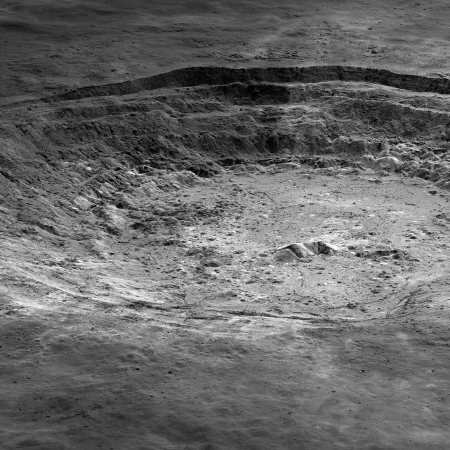

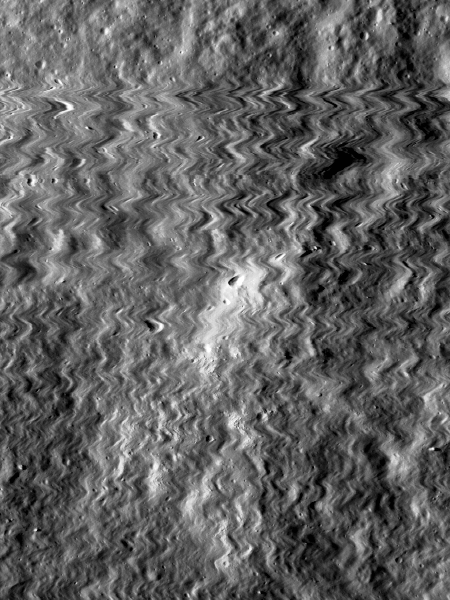

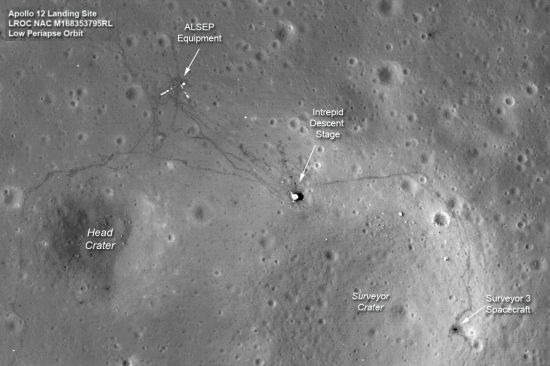

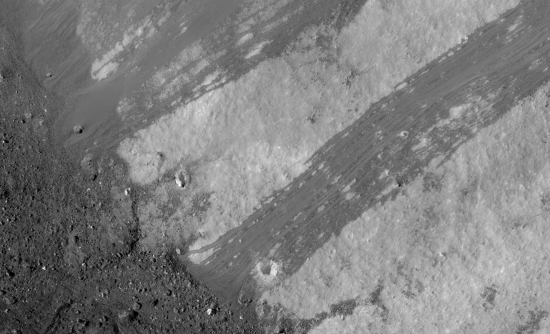

By referencing the footage released by China of Chang’e-4’s descent onto the Moon, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) team has been able to pinpoint exactly where the lander touched down. The image on the right has been reduced slightly. Click on it to see it in full resolution.

The largest nearby crater to the lander is estimated to be about 80 feet across.

Because the images were in December 2018 before the lander’s arrival, they do not show it. However, the LRO team now knows exactly where to look when they take new pictures in the next few weeks. Moreover, this will allow them to monitor Yutu-2’s travels as it roves the surface over the coming months.

By referencing the footage released by China of Chang’e-4’s descent onto the Moon, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) team has been able to pinpoint exactly where the lander touched down. The image on the right has been reduced slightly. Click on it to see it in full resolution.

The largest nearby crater to the lander is estimated to be about 80 feet across.

Because the images were in December 2018 before the lander’s arrival, they do not show it. However, the LRO team now knows exactly where to look when they take new pictures in the next few weeks. Moreover, this will allow them to monitor Yutu-2’s travels as it roves the surface over the coming months.