Ingenuity’s fourth flight today

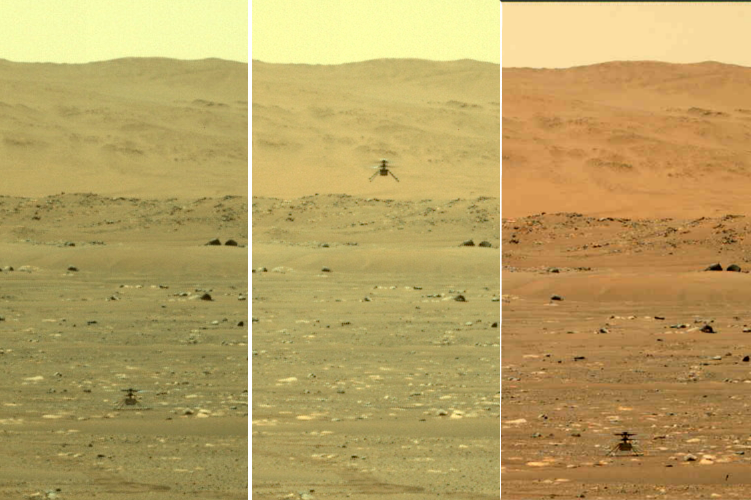

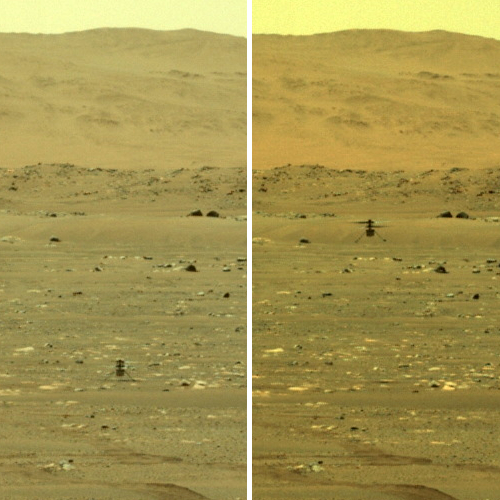

The fourth flight of the Mars helicopter Ingenuity has just occurred, with data arriving momentarily.

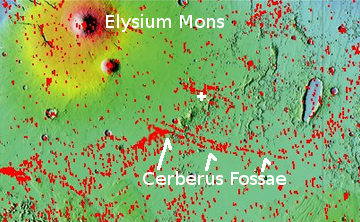

The fourth Ingenuity flight from Wright Brothers Field, the name for the Martian airfield on which the flight took place, is scheduled to take off Thursday, April 29, at 10:12 a.m. EDT (7:12 a.m. PDT, 12:30 p.m. local Mars time), with the first data expected back at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California at 1:21 p.m. EDT (10:21 a.m. PDT).

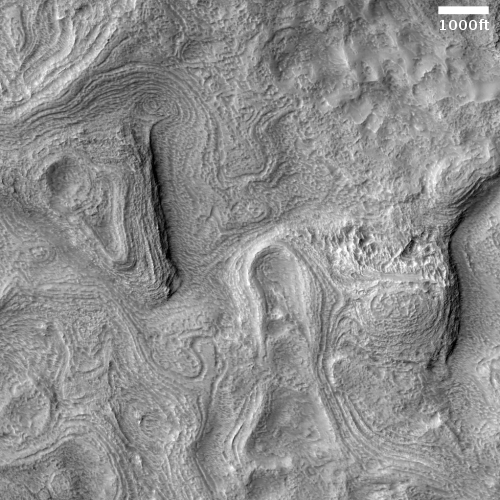

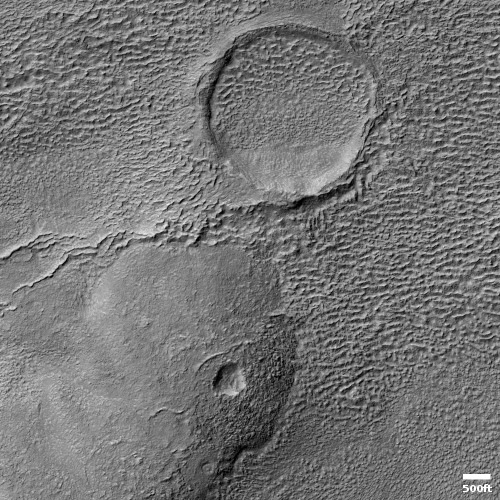

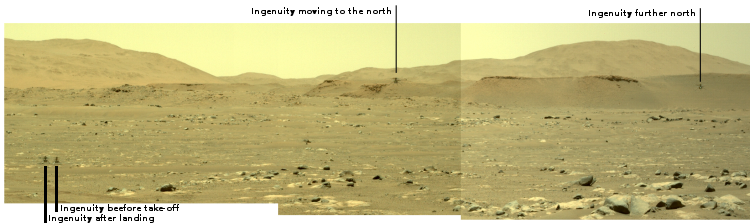

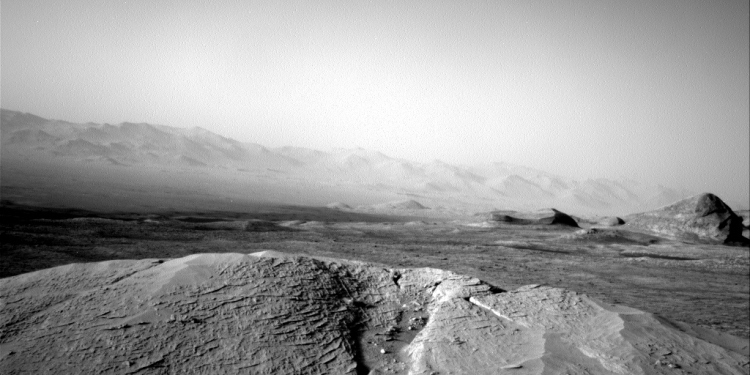

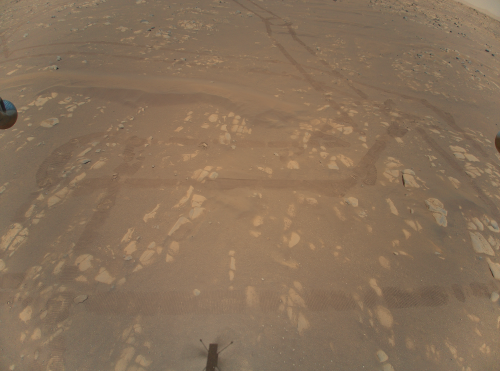

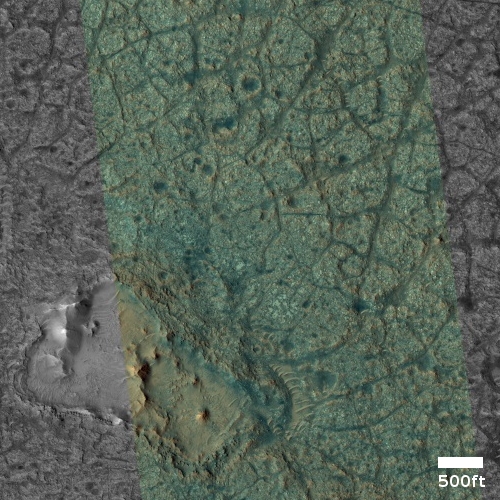

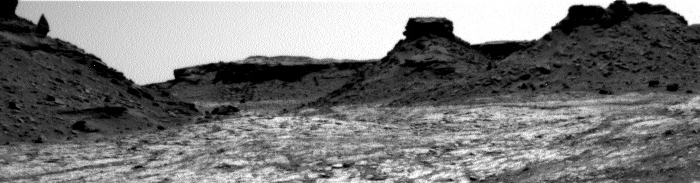

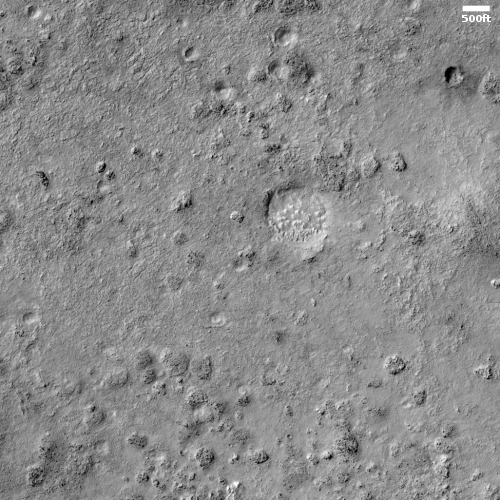

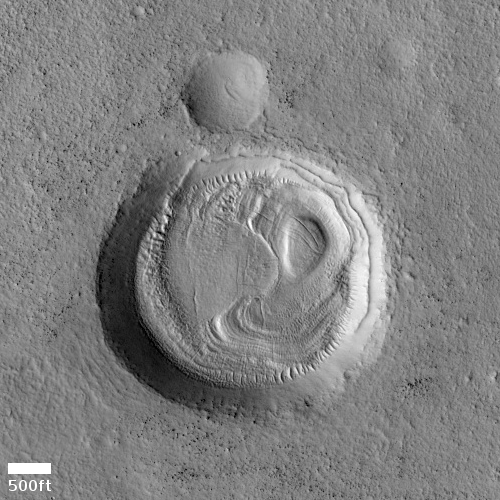

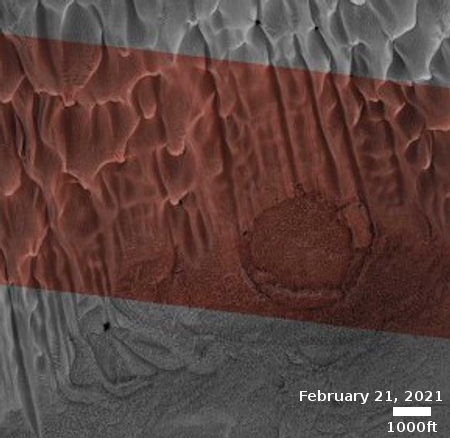

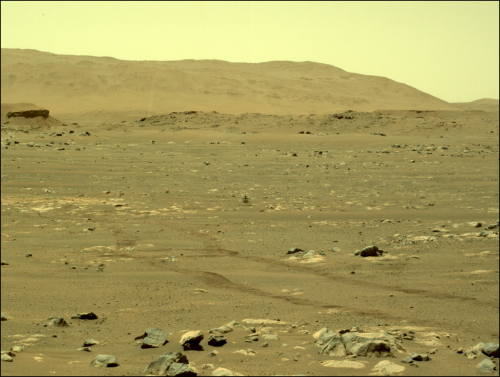

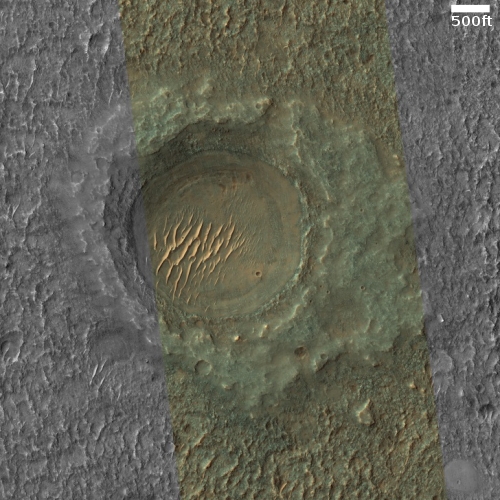

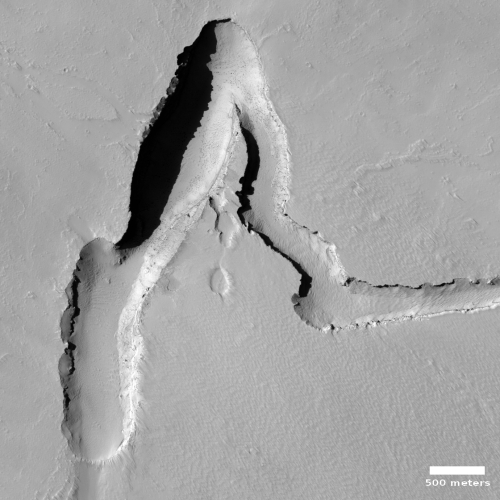

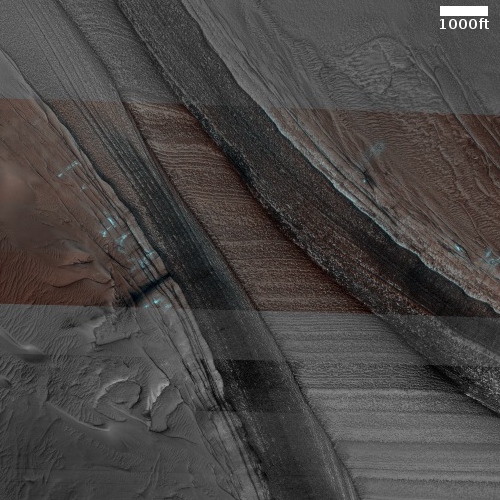

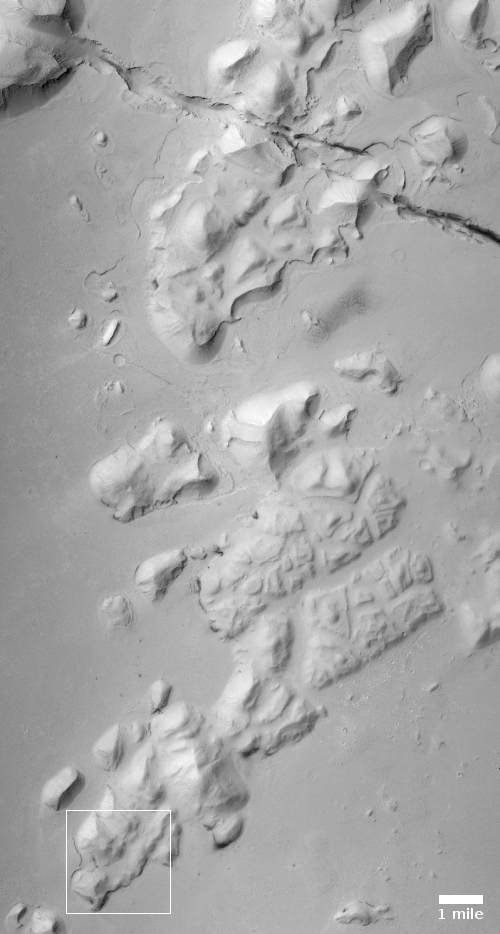

…Flight Four sets out to demonstrate the potential value of that aerial perspective. The flight test will begin with Ingenuity climbing to an altitude of 16 feet (5 meters) and then heading south, flying over rocks, sand ripples, and small impact craters for 276 feet (84 meters). As it flies, the rotorcraft will use its downward-looking navigation camera to collect images of the surface every 4 feet (1.2 meters) from that point until it travels a total of 436 feet (133 meters) downrange. Then, Ingenuity will go into a hover and take images with its color camera before heading back to Wright Brothers Field.

Stay tuned for new images. NASA will also hold a press conference tomorrow to outline the results and the rest of Ingenuity’s test program.

The fourth flight of the Mars helicopter Ingenuity has just occurred, with data arriving momentarily.

The fourth Ingenuity flight from Wright Brothers Field, the name for the Martian airfield on which the flight took place, is scheduled to take off Thursday, April 29, at 10:12 a.m. EDT (7:12 a.m. PDT, 12:30 p.m. local Mars time), with the first data expected back at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California at 1:21 p.m. EDT (10:21 a.m. PDT).

…Flight Four sets out to demonstrate the potential value of that aerial perspective. The flight test will begin with Ingenuity climbing to an altitude of 16 feet (5 meters) and then heading south, flying over rocks, sand ripples, and small impact craters for 276 feet (84 meters). As it flies, the rotorcraft will use its downward-looking navigation camera to collect images of the surface every 4 feet (1.2 meters) from that point until it travels a total of 436 feet (133 meters) downrange. Then, Ingenuity will go into a hover and take images with its color camera before heading back to Wright Brothers Field.

Stay tuned for new images. NASA will also hold a press conference tomorrow to outline the results and the rest of Ingenuity’s test program.