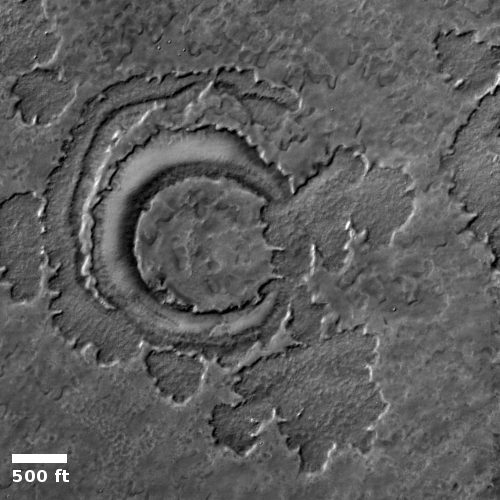

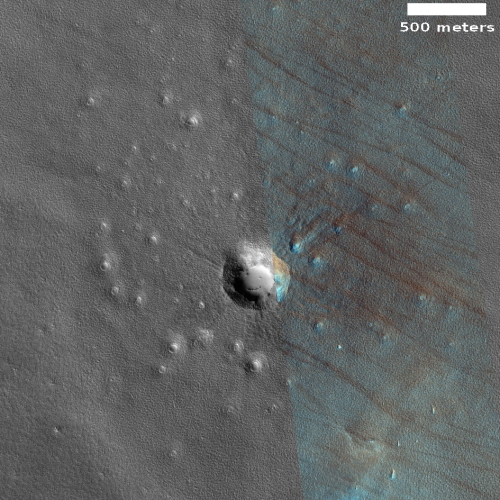

Craters in slush on Mars

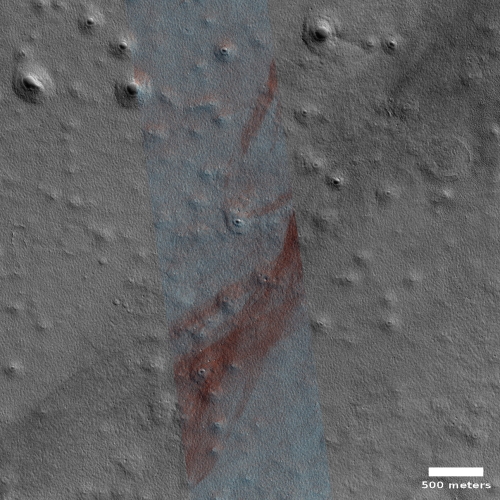

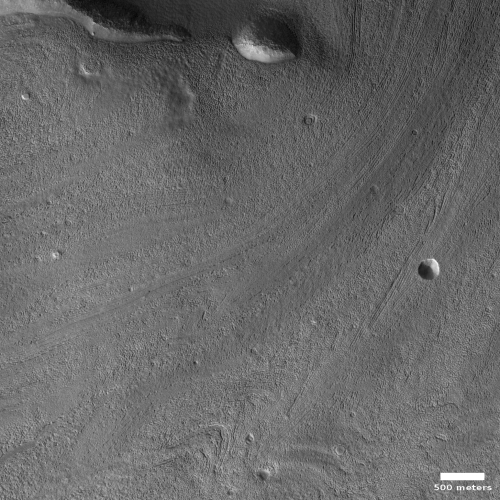

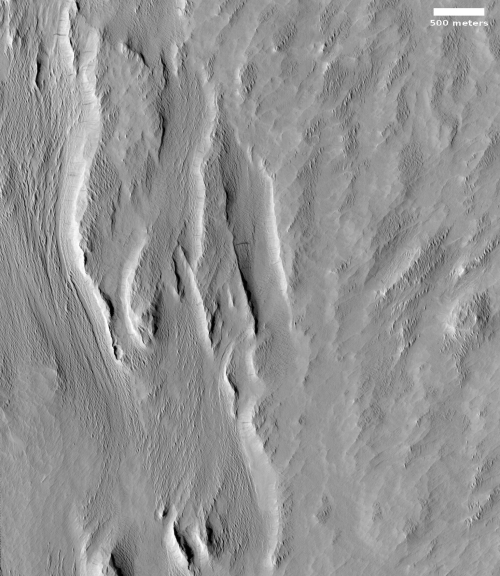

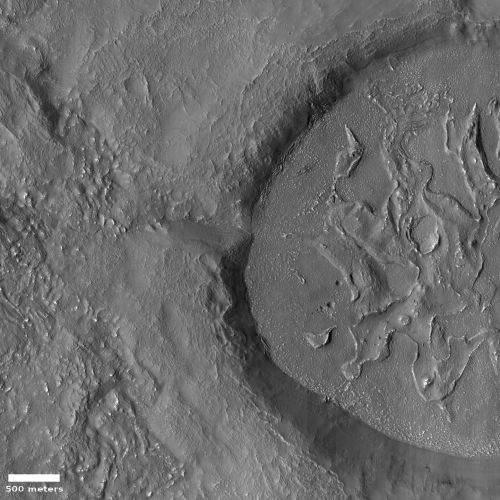

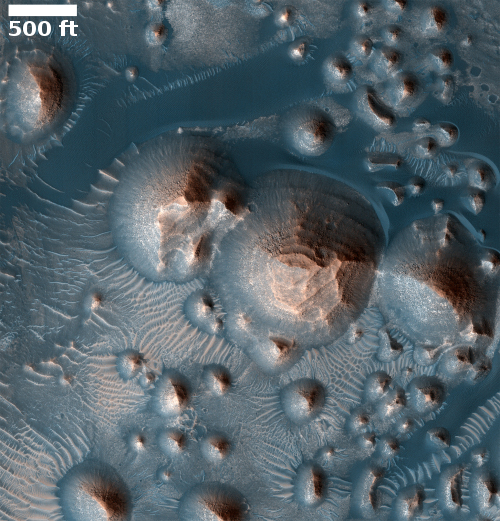

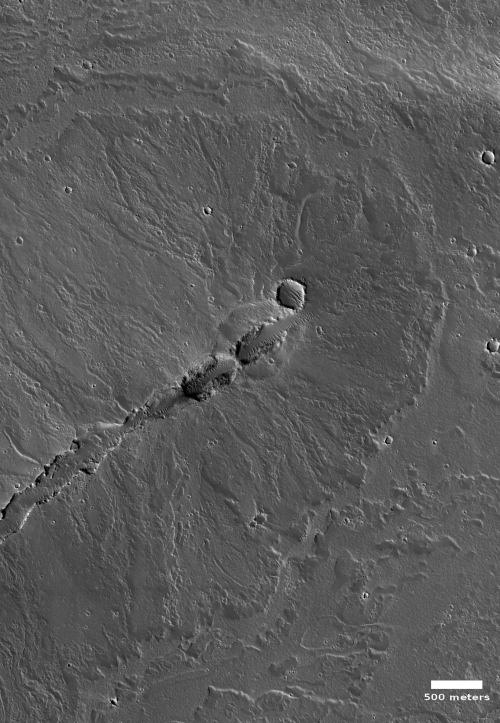

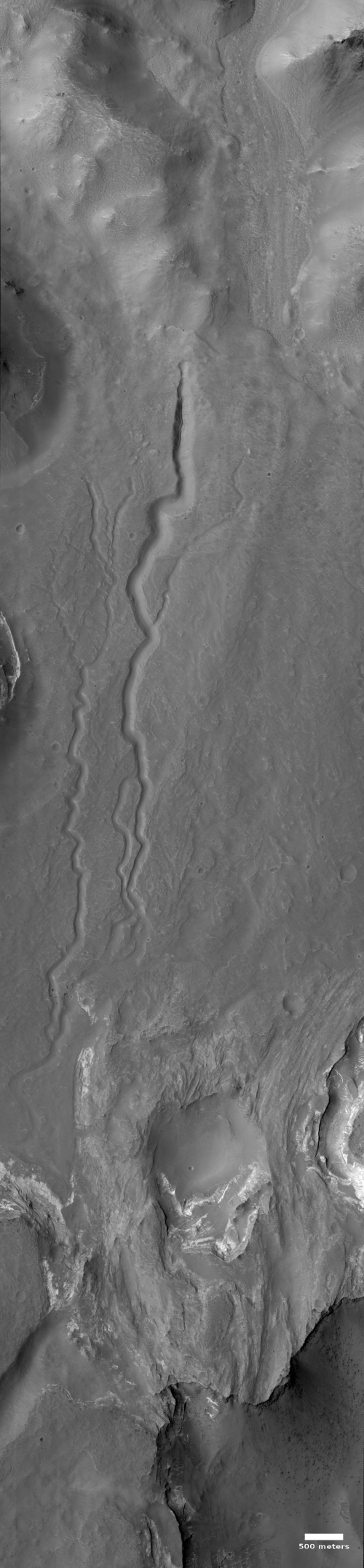

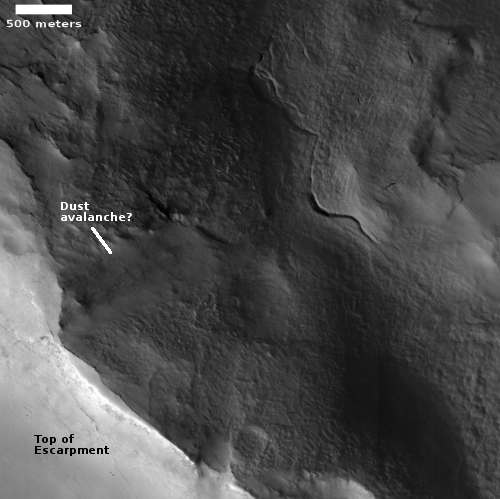

Cool image time! The photo to the right, cropped and reduced to post here, was taken on October 27, 2020 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). It was taken not for any particular research project, but as one of the periodic images the camera team needs to take maintain the camera’s proper temperature. When they need to do this, they often will take a picture in an area not previously viewed at high resolution. Sometimes the image is boring. Sometimes they photograph some geology that is really fascinating, and begs for some young scientist to devote some effort to studying it.

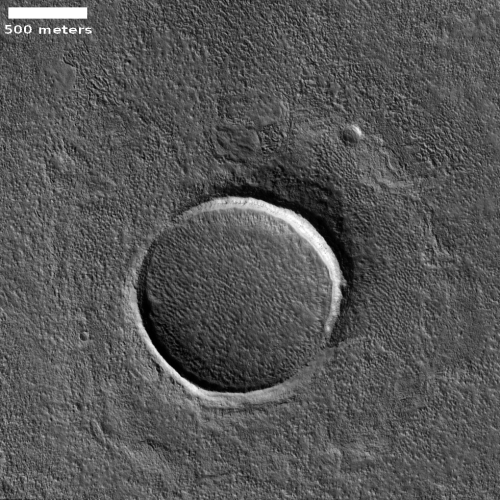

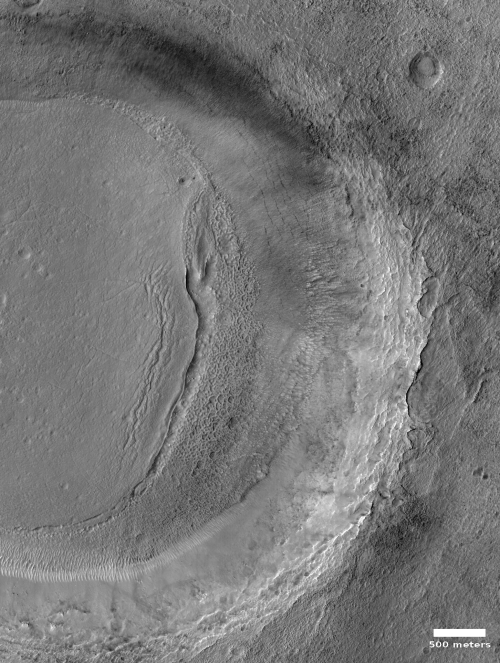

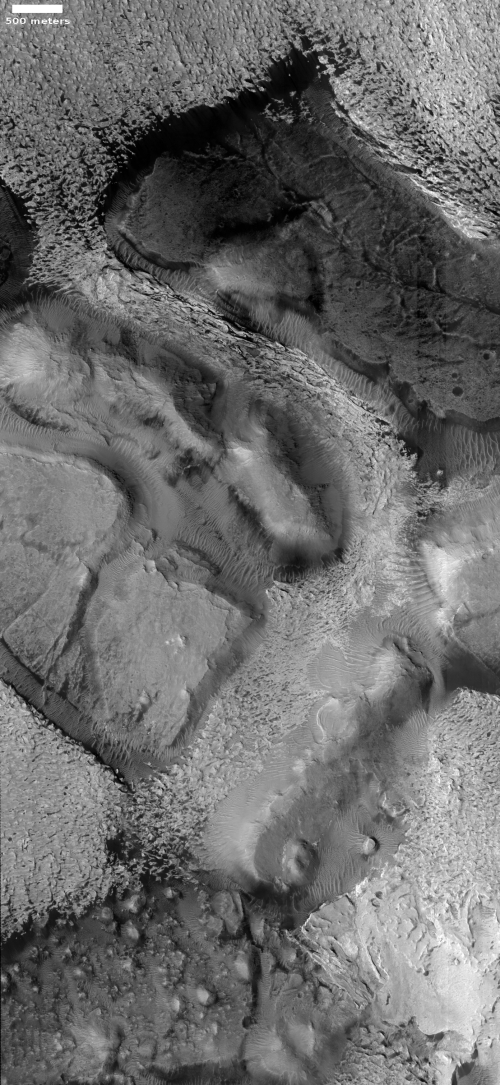

In this case the photo was of the generally featureless northern lowland plains. What the image shows us is a scattering of impact craters that appear to have cut into a flat plain likely saturated with ice very close to the surface.

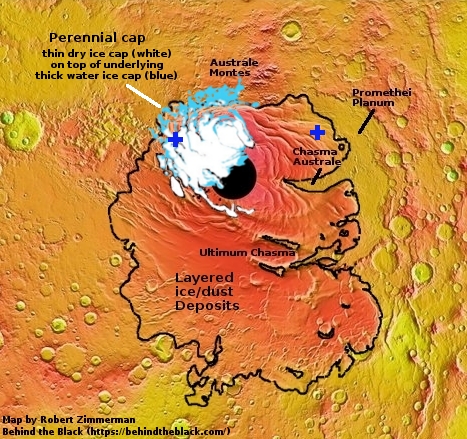

How can I conclude so confidently that these craters impacted into ice close to the surface? The location gives it away.

» Read more

Cool image time! The photo to the right, cropped and reduced to post here, was taken on October 27, 2020 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). It was taken not for any particular research project, but as one of the periodic images the camera team needs to take maintain the camera’s proper temperature. When they need to do this, they often will take a picture in an area not previously viewed at high resolution. Sometimes the image is boring. Sometimes they photograph some geology that is really fascinating, and begs for some young scientist to devote some effort to studying it.

In this case the photo was of the generally featureless northern lowland plains. What the image shows us is a scattering of impact craters that appear to have cut into a flat plain likely saturated with ice very close to the surface.

How can I conclude so confidently that these craters impacted into ice close to the surface? The location gives it away.

» Read more