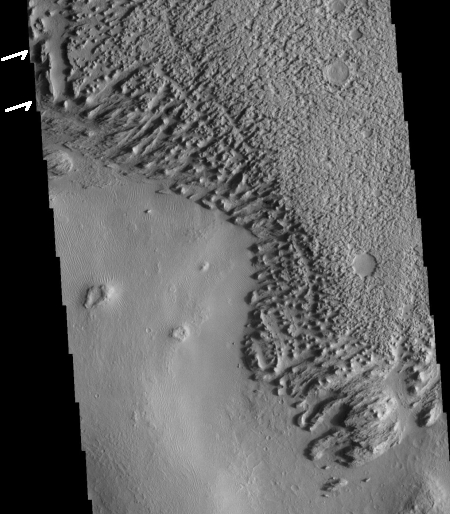

Click for full image.

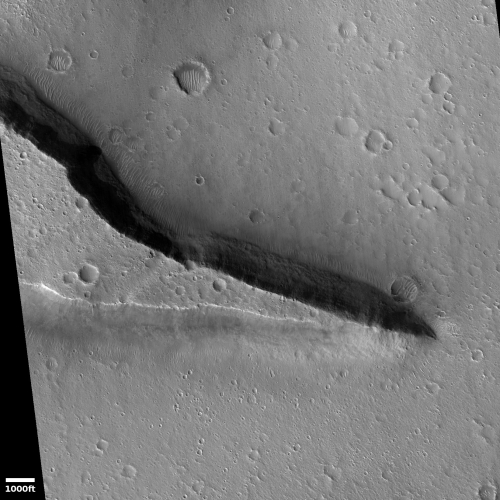

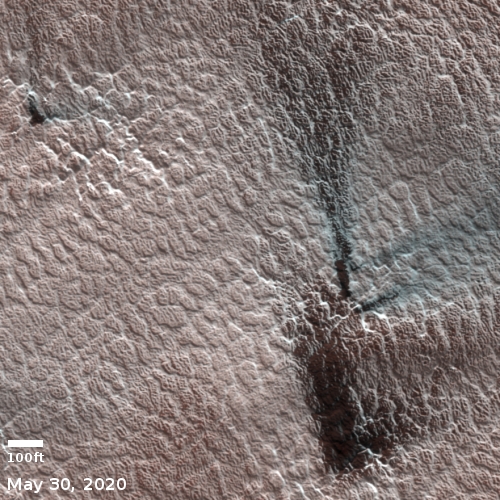

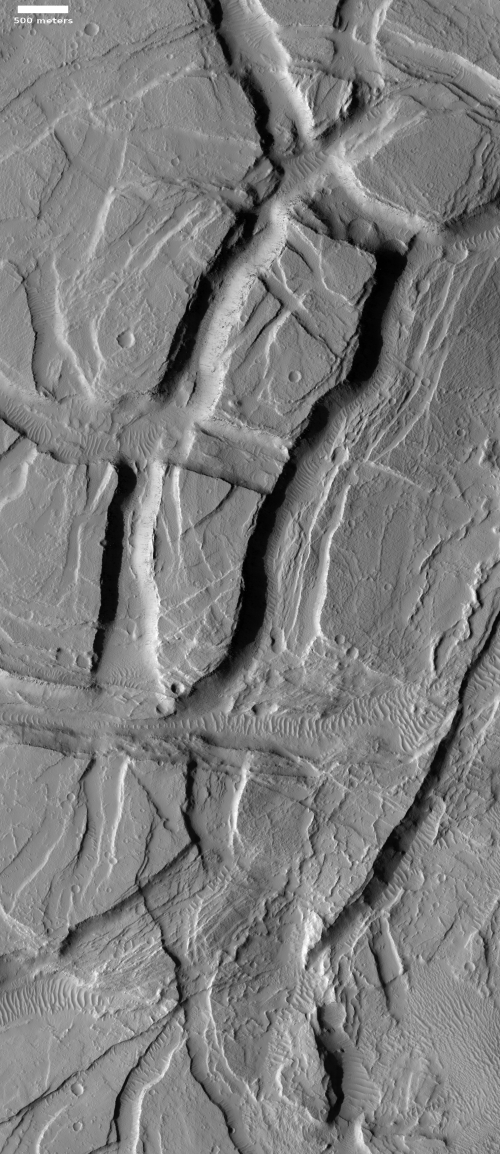

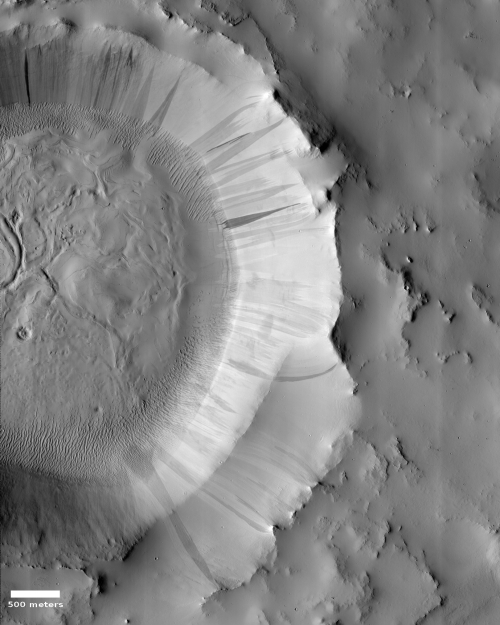

Cool image time! I’ve covered the topic of the mysterious slope streaks on Mars previously in great detail (see here and here). Essentially they are generally dark streaks (but sometimes light) that appear randomly on slopes and then fade over time. Unlike recurring slope lineae, another changing streak found on Martian slopes, the coming and going of slope streaks is not tied to the seasons. They can appear at any time in the year, and will take several Martian years to fade away.

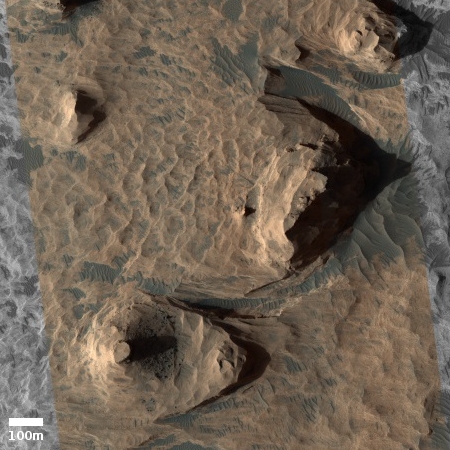

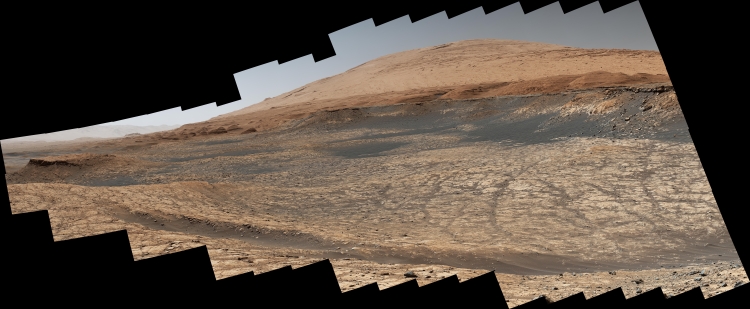

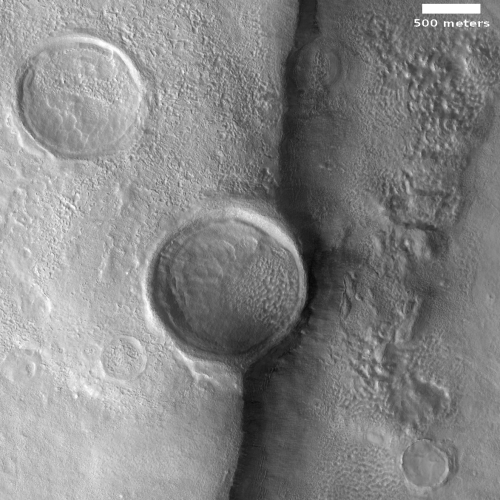

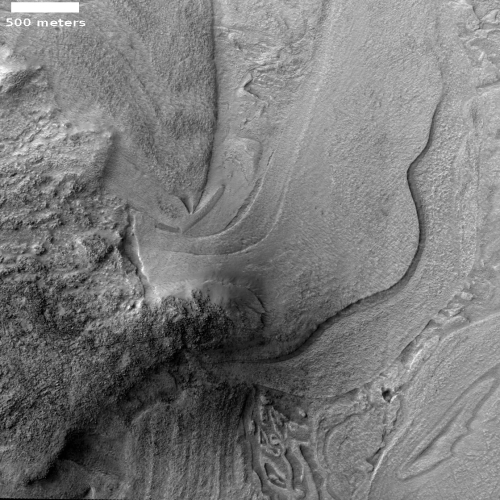

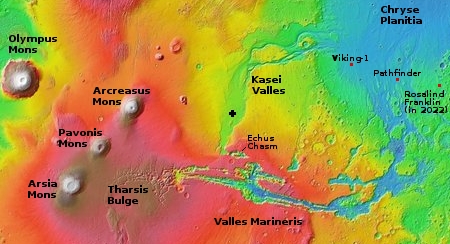

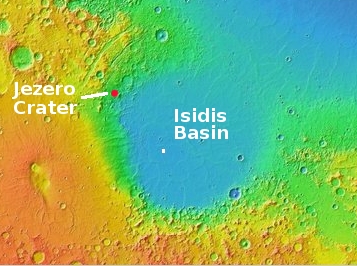

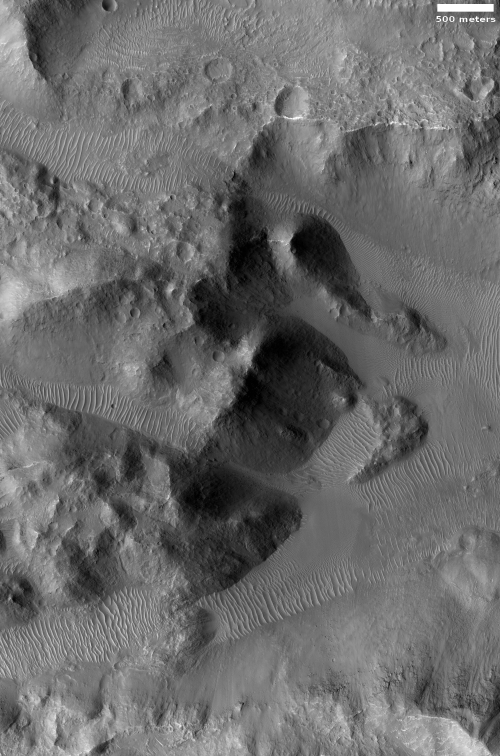

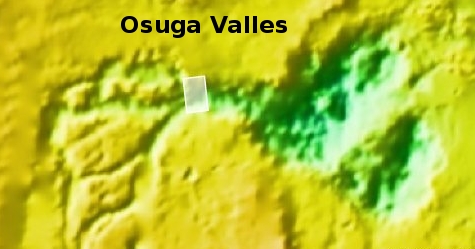

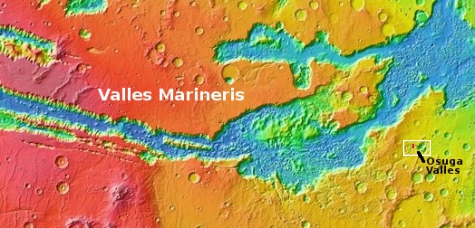

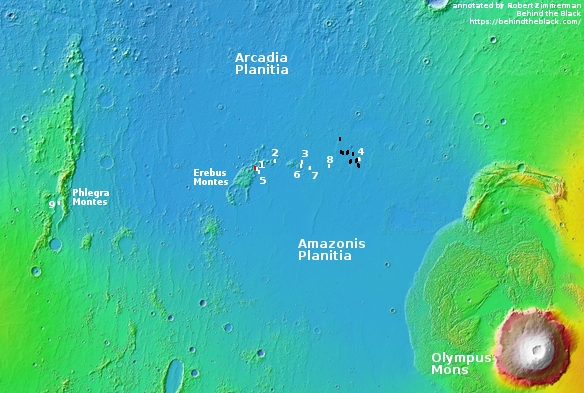

The image to the right, rotated, cropped, and reduced to post here, was taken by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) on March 26, 2020. It shows numerous slope streaks down the eastern interior rim of a crater in the transition zone between the northern lowlands and the southern cratered highlands in a region dubbed Arabia Terra.

Though I can find no previous high resolution image of this crater to measure any temporal changes, you can clearly see that this slope has experienced many streaks over time, with some darker than others. The different shades suggest that the lighter streaks are older and have faded, with the darker streaks more recent events.

At the moment there is no strong consensus on the causes of these streaks. As one science paper noted, “The processes that form slope streaks remain obscure. No proposed mechanism readily accounts for all of their observed characteristics and peculiarities.” We know they occur in equatorial regions and dusty locations, and that they are triggered by some disturbance at the topmost point of the streak, which then causes a chain reaction down the slope. Other than that, the facts are puzzling, and suggest that these streaks are a phenomenon wholly unique to Mars.

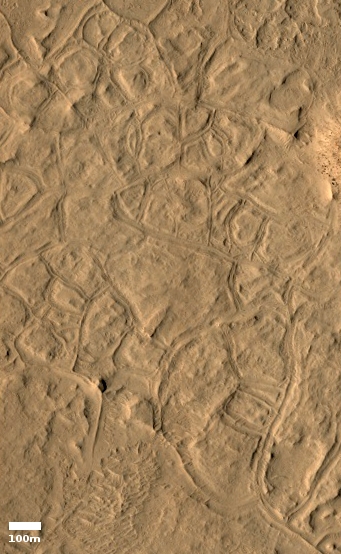

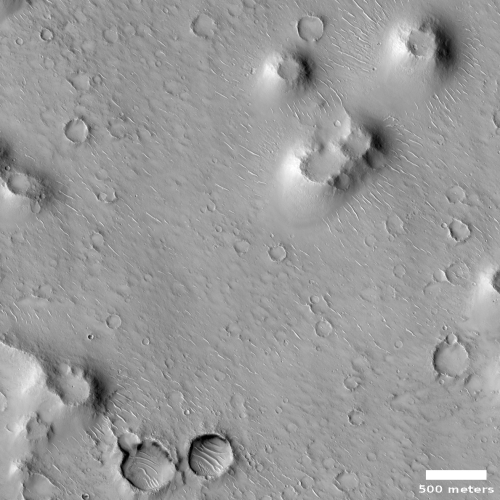

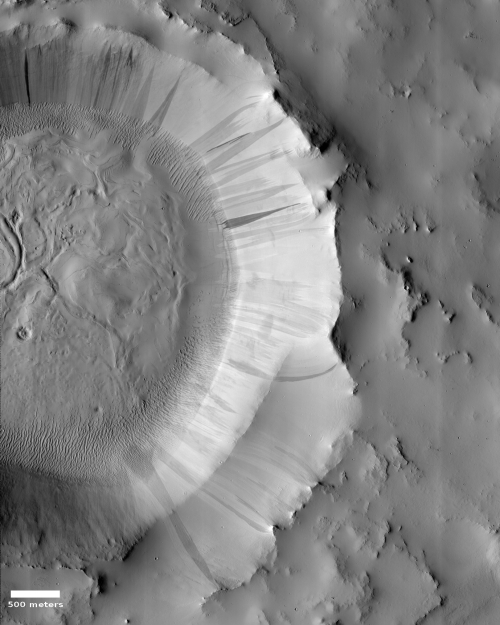

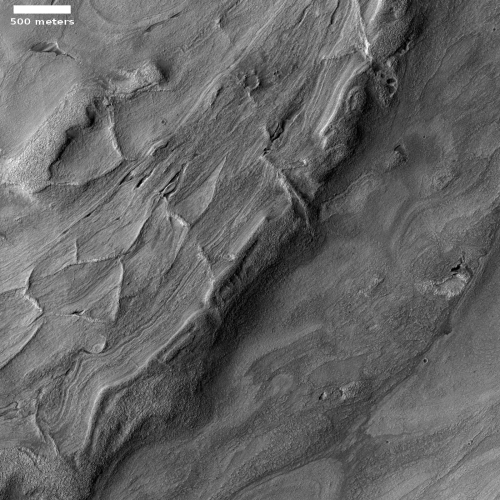

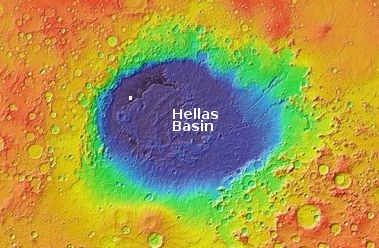

The crater itself, located at 24 degrees north latitude, has some other mysteries. The features on its floor, for instance, are very puzzling. Though suggestive of the buried glaciers found in many craters in the mid-latitudes, this crater is a bit too far south. Maybe its higher altitude allows for some ice to remain here? Then again, the features on that floor might have nothing to do with ice. Maybe we are looking at sand carved by wind? Or hardened mud that was once wet?

I am merely guessing, a dangerous thing to do when one’s knowledge is limited. Then again, it’s fun, so please join in with your own guesses.