Where are the caves on Mars?

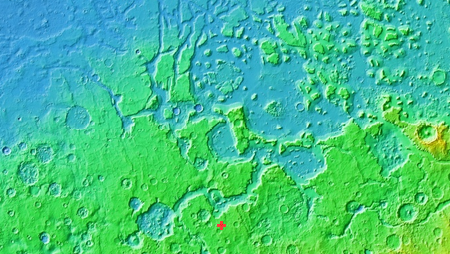

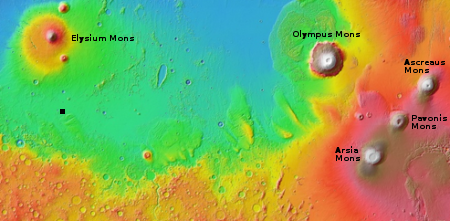

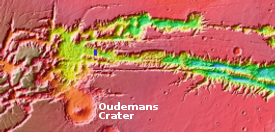

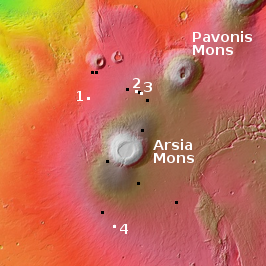

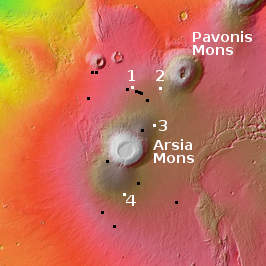

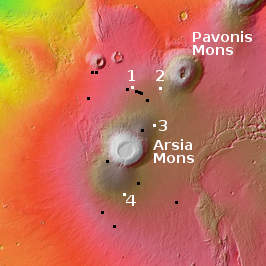

Each month I go through the monthly download of new images from the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). And each month since November I have found a bunch of newly discovered pits photographed in the region around the volcano Arsia Mons (see: November 12, 2018, January 30, 2019, February 22, 2019, April 2, 2019, and May 7, 2019). The map on the right has been updated to include all those previous pits, indicated by the black boxes, with the new pits from June shown by the numbered white boxes.

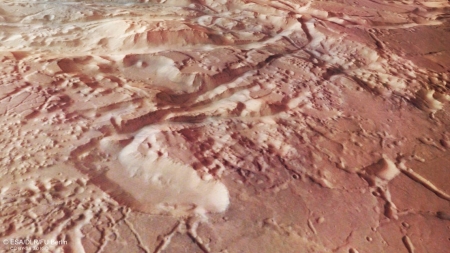

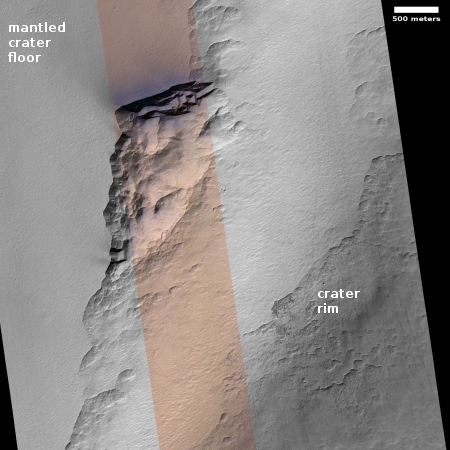

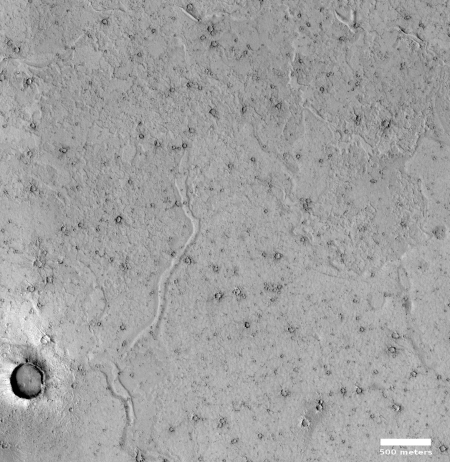

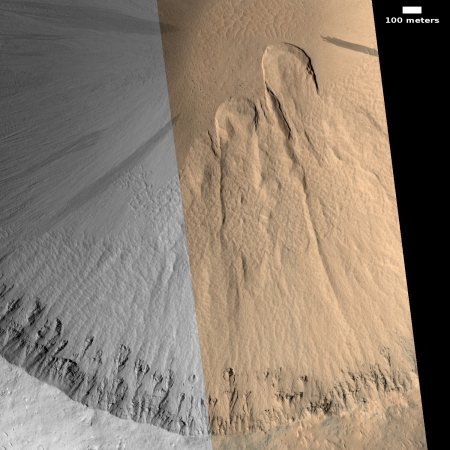

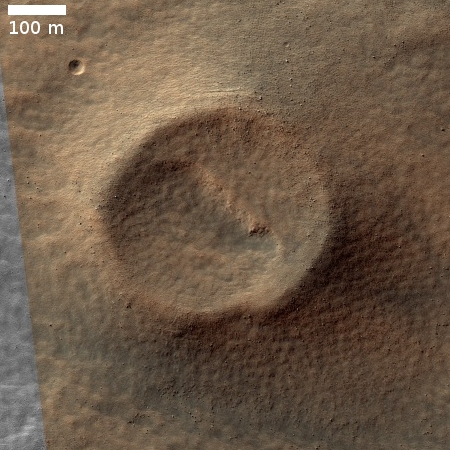

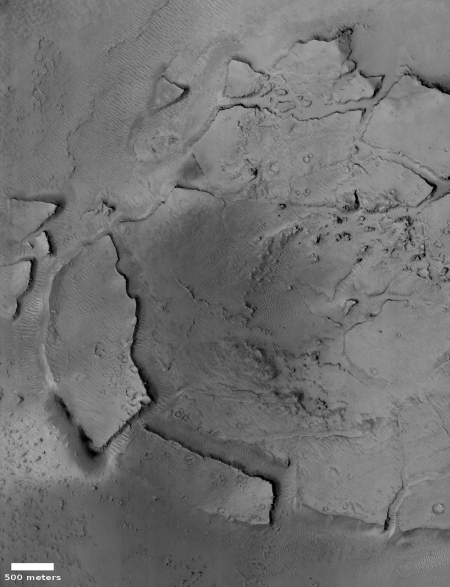

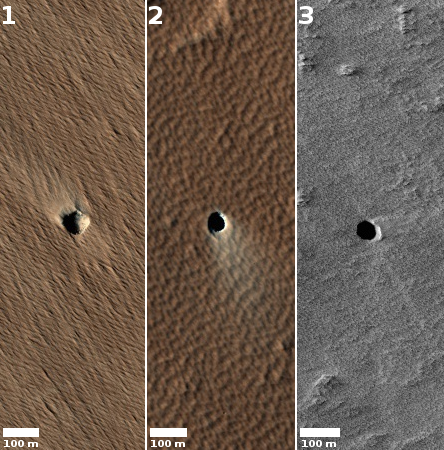

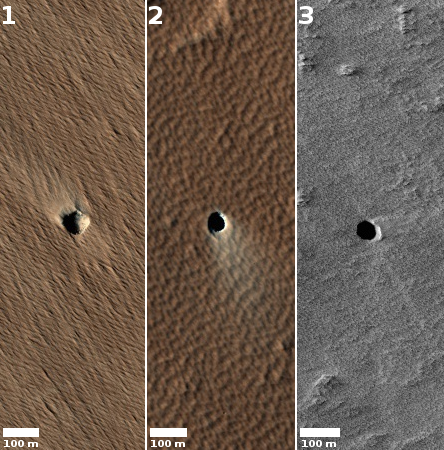

To the right are the first three pits in the June archive, with the link to each image site found here (#1), here (#2), and here (#3).

For full images: Number 1, Number 2, Number 3.

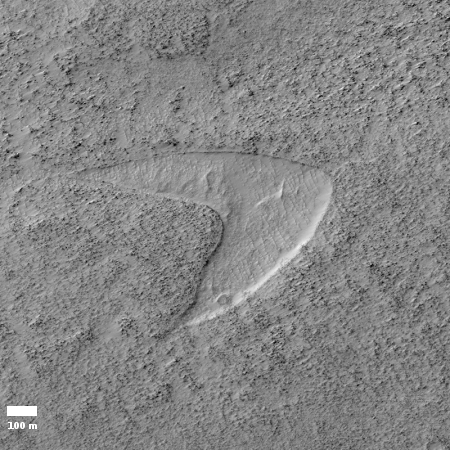

All three are what the scientists doing this research call Atypical Pit Craters:

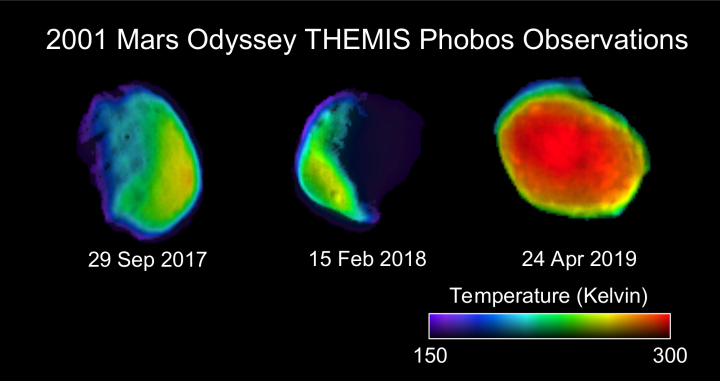

These Atypical Pit Craters (APCs) generally have sharp and distinct rims, vertical or overhanging walls that extend down to their floors, surface diameters of ~50–350 m, and high depth to diameter (d/D) ratios that are usually greater than 0.3 (which is an upper range value for impacts and bowl-shaped pit craters) and can exceed values of 1.8. Observations by the Mars Odyssey Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) show that APC floor temperatures are warmer at night and fluctuate with much lower diurnal amplitudes than nearby surfaces or adjacent bowl-shaped pit craters.

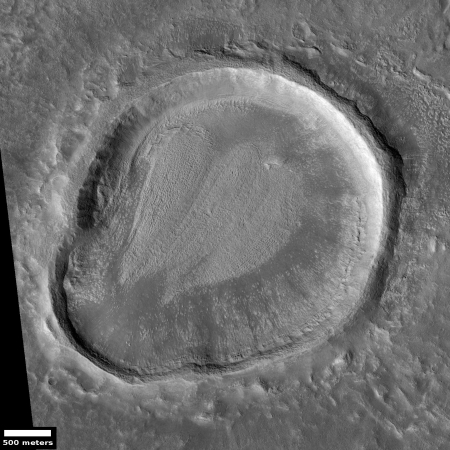

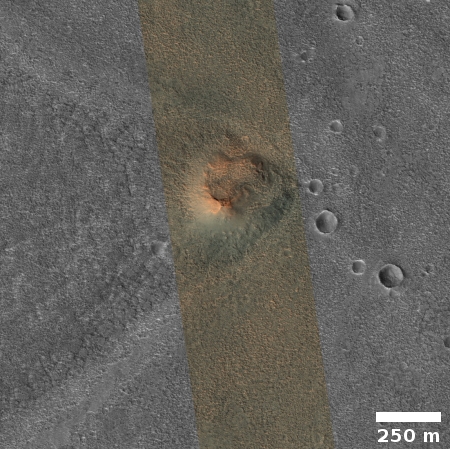

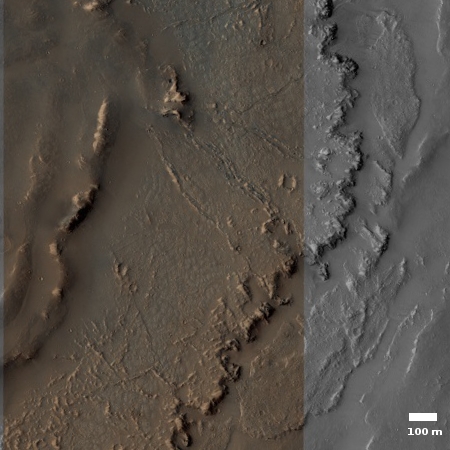

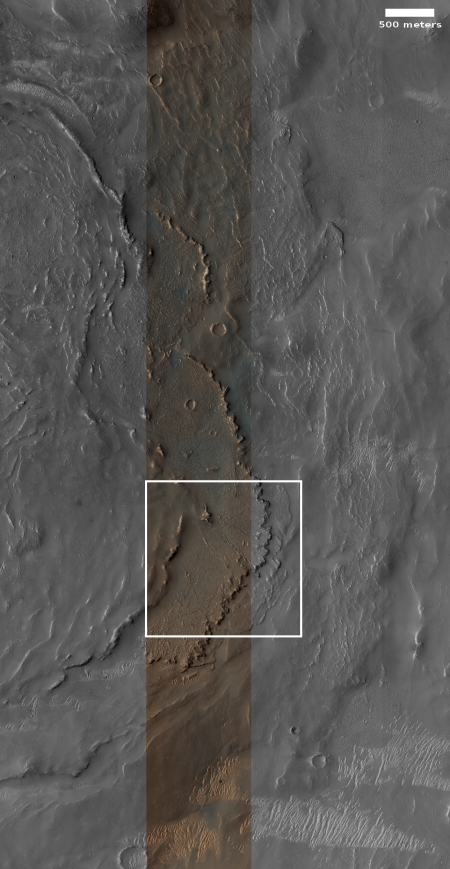

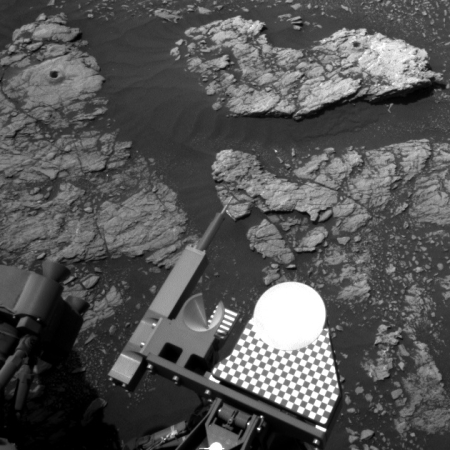

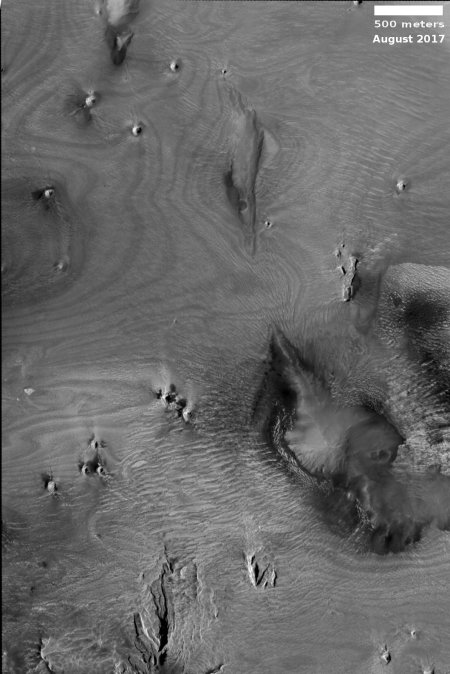

The fourth pit, shown in the reduced and cropped image below, might actually be the most interesting of the June lot.

» Read more

Each month I go through the monthly download of new images from the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). And each month since November I have found a bunch of newly discovered pits photographed in the region around the volcano Arsia Mons (see: November 12, 2018, January 30, 2019, February 22, 2019, April 2, 2019, and May 7, 2019). The map on the right has been updated to include all those previous pits, indicated by the black boxes, with the new pits from June shown by the numbered white boxes.

To the right are the first three pits in the June archive, with the link to each image site found here (#1), here (#2), and here (#3).

For full images: Number 1, Number 2, Number 3.

All three are what the scientists doing this research call Atypical Pit Craters:

These Atypical Pit Craters (APCs) generally have sharp and distinct rims, vertical or overhanging walls that extend down to their floors, surface diameters of ~50–350 m, and high depth to diameter (d/D) ratios that are usually greater than 0.3 (which is an upper range value for impacts and bowl-shaped pit craters) and can exceed values of 1.8. Observations by the Mars Odyssey Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) show that APC floor temperatures are warmer at night and fluctuate with much lower diurnal amplitudes than nearby surfaces or adjacent bowl-shaped pit craters.

The fourth pit, shown in the reduced and cropped image below, might actually be the most interesting of the June lot.

» Read more