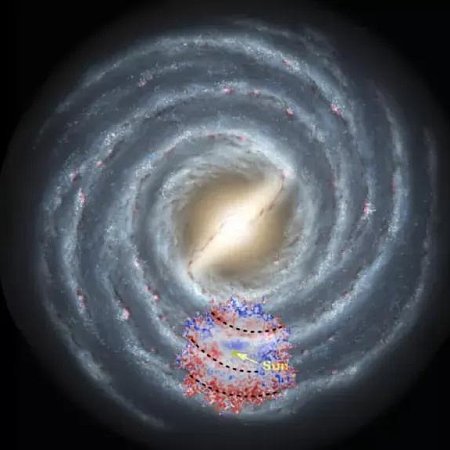

Astronomers chemically map a significant portion of the Milky Way

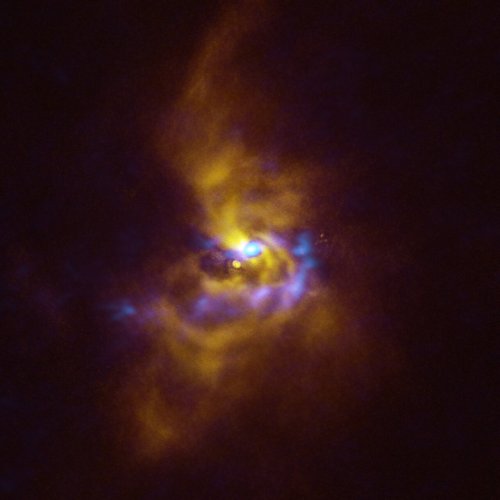

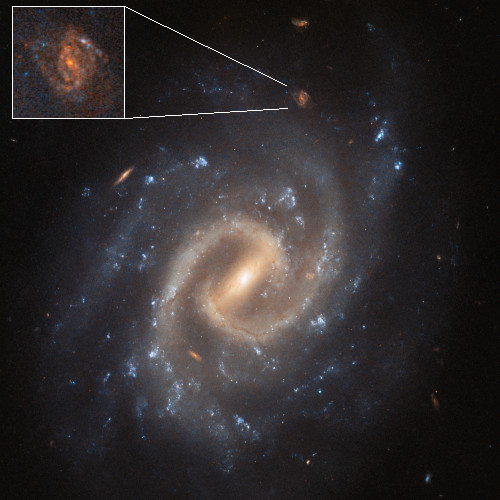

Red indicates areas with lots of heavier elements, blue indicates

areas dominated by hydrogen and helium. Click for original image.

Astronomers have now used today’s modern survey telescopes — on Earth and in space — to map the chemistry of a large portion of the Milky Way’s nearby spiral arms, revealing that the arms themselves are rich in heavier elements, indicating greater age and the right materials to produce new stars and solar systems like our own.

If the Milky Way’s spiral arms trigger star births as predicted, then they should be marked by young stars, aka metal-rich stars. Conversely, spaces between the arms should be marked by metal-poor stars.

To confirm this theory, as well as create his overall map of metalicity, Hawkins first looked at our solar system’s galactic backyard, which include stars about 32,000 light years from the sun. In cosmic terms, that represents our stellar neighborhood’s immediate vicinity.

Taking the resultant map, the researcher compared it to others of the same area of the Milky Way created by different techniques, finding that the positions of the spiral arms lined up. And, because he used metalicity to chart the spiral arms, hitherto unseen regions of the Milky Way’s spiral arms showed up in Hawkins’ map. “A big takeaway is that the spiral arms are indeed richer in metals,” Hawkins explained. “This illustrates the value of chemical cartography in identifying the Milky Way’s structure and formation. It has the potential to fully transform our view of the Galaxy.”

You can read the science paper here [pdf]. Based on this initial mapping effort, it appears that it will not be long before a large percentage of our own galaxy will be mapped in this manner.

Red indicates areas with lots of heavier elements, blue indicates

areas dominated by hydrogen and helium. Click for original image.

Astronomers have now used today’s modern survey telescopes — on Earth and in space — to map the chemistry of a large portion of the Milky Way’s nearby spiral arms, revealing that the arms themselves are rich in heavier elements, indicating greater age and the right materials to produce new stars and solar systems like our own.

If the Milky Way’s spiral arms trigger star births as predicted, then they should be marked by young stars, aka metal-rich stars. Conversely, spaces between the arms should be marked by metal-poor stars.

To confirm this theory, as well as create his overall map of metalicity, Hawkins first looked at our solar system’s galactic backyard, which include stars about 32,000 light years from the sun. In cosmic terms, that represents our stellar neighborhood’s immediate vicinity.

Taking the resultant map, the researcher compared it to others of the same area of the Milky Way created by different techniques, finding that the positions of the spiral arms lined up. And, because he used metalicity to chart the spiral arms, hitherto unseen regions of the Milky Way’s spiral arms showed up in Hawkins’ map. “A big takeaway is that the spiral arms are indeed richer in metals,” Hawkins explained. “This illustrates the value of chemical cartography in identifying the Milky Way’s structure and formation. It has the potential to fully transform our view of the Galaxy.”

You can read the science paper here [pdf]. Based on this initial mapping effort, it appears that it will not be long before a large percentage of our own galaxy will be mapped in this manner.