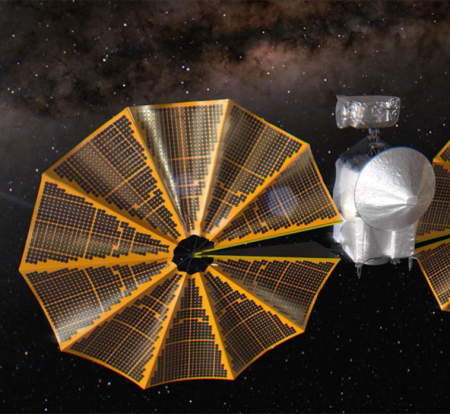

After 50 years Edward Stone retires as the project scientist for Voyagers 1 and 2

Edward Stone, the only project scientist the interstellar spacecraft Voyagers 1 and 2 have ever known, has now retired after 50 years service.

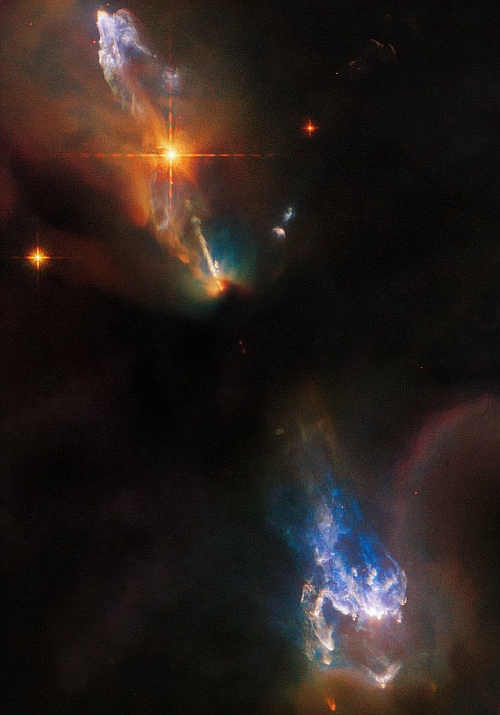

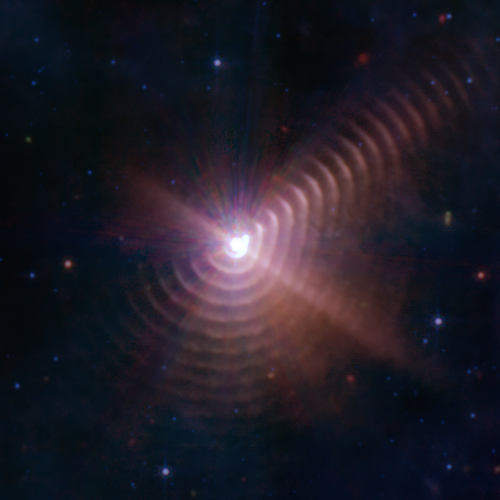

Stone accepted scientific leadership of the historic mission in 1972, five years before the launch of its two spacecraft, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. Under his guidance, the Voyagers explored the four giant planets and became the first human-made objects to reach interstellar space, the region between the stars containing material generated by the death of nearby stars.

Until now, Stone was the only person to have served as project scientist for Voyager, maintaining his position even while serving as director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California from 1991 to 2001. JPL manages the Voyager mission for NASA. Stone retired from JPL in 2001 but continued to serve as the mission’s project scientist.

The new Voyager project scientist however is not new to the project.

Linda Spilker will succeed Stone as Voyager’s project scientist as the twin probes continue to explore interstellar space. Spilker was a member of the Voyager science team during the mission’s flybys of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. She later became project scientist for NASA’s now-retired Cassini mission to Saturn, and rejoined Voyager as deputy project scientist in 2021.

Edward Stone, the only project scientist the interstellar spacecraft Voyagers 1 and 2 have ever known, has now retired after 50 years service.

Stone accepted scientific leadership of the historic mission in 1972, five years before the launch of its two spacecraft, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. Under his guidance, the Voyagers explored the four giant planets and became the first human-made objects to reach interstellar space, the region between the stars containing material generated by the death of nearby stars.

Until now, Stone was the only person to have served as project scientist for Voyager, maintaining his position even while serving as director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California from 1991 to 2001. JPL manages the Voyager mission for NASA. Stone retired from JPL in 2001 but continued to serve as the mission’s project scientist.

The new Voyager project scientist however is not new to the project.

Linda Spilker will succeed Stone as Voyager’s project scientist as the twin probes continue to explore interstellar space. Spilker was a member of the Voyager science team during the mission’s flybys of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. She later became project scientist for NASA’s now-retired Cassini mission to Saturn, and rejoined Voyager as deputy project scientist in 2021.