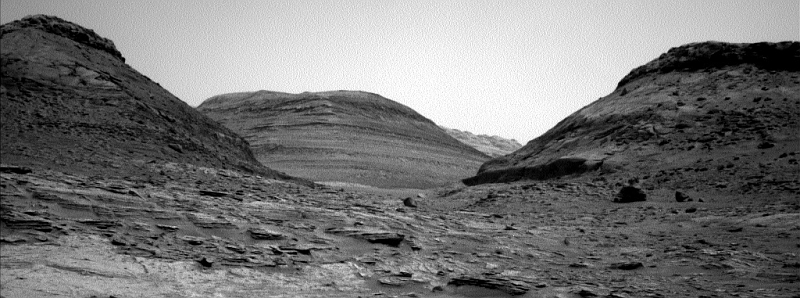

A major update from Curiosity’s science team

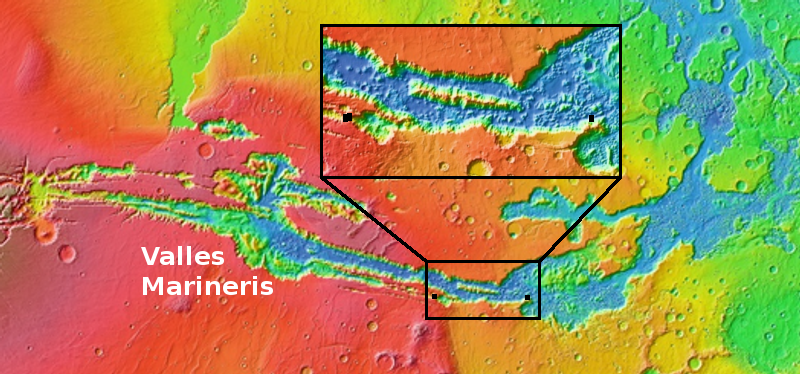

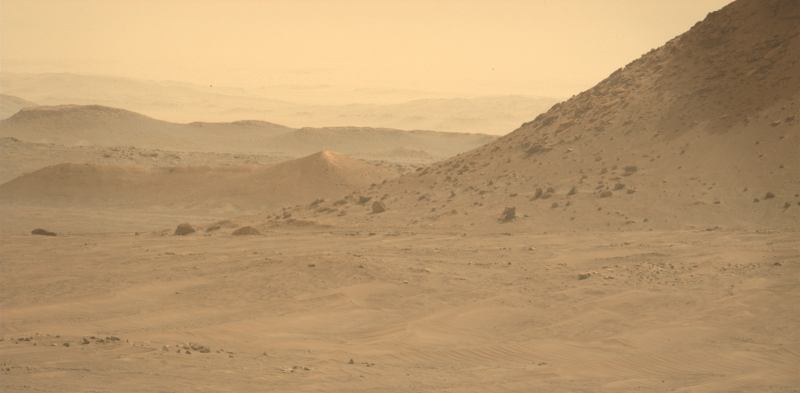

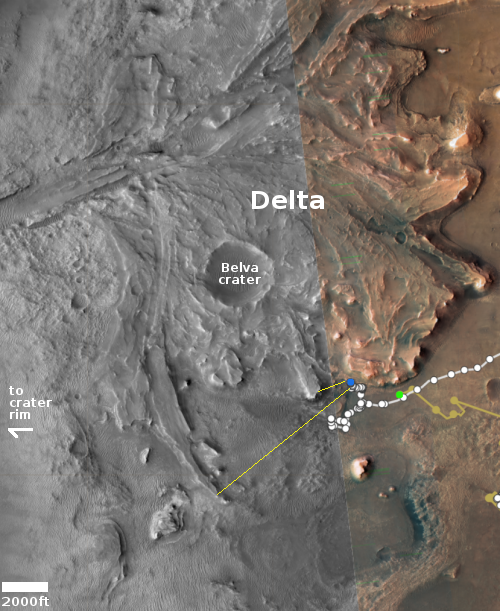

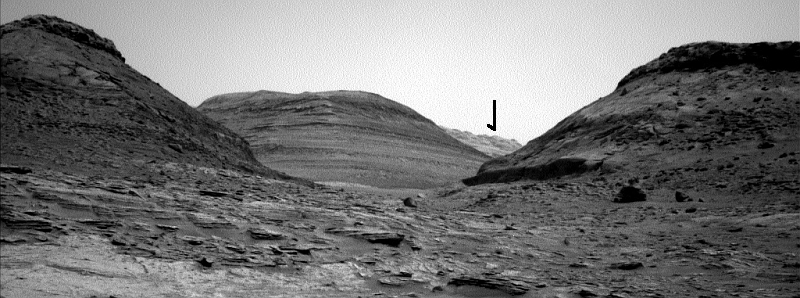

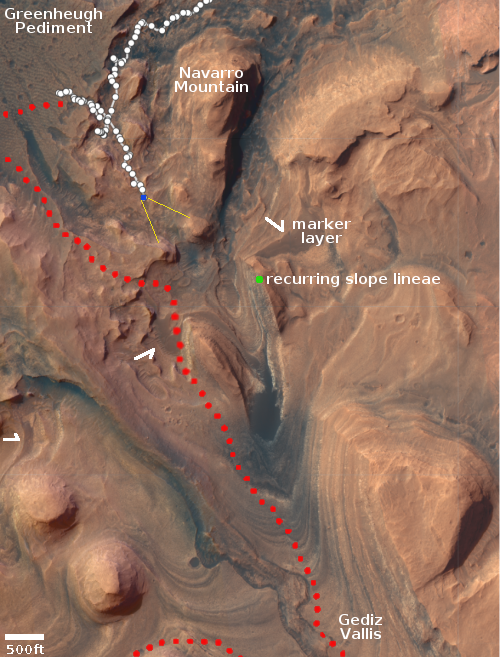

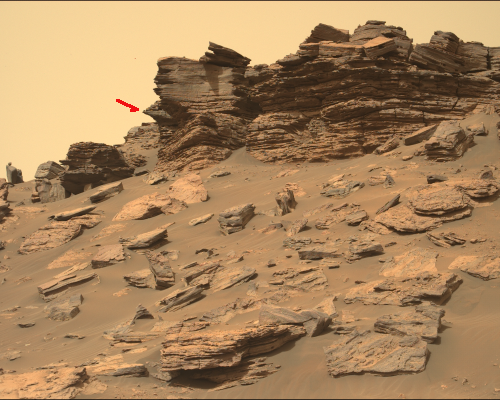

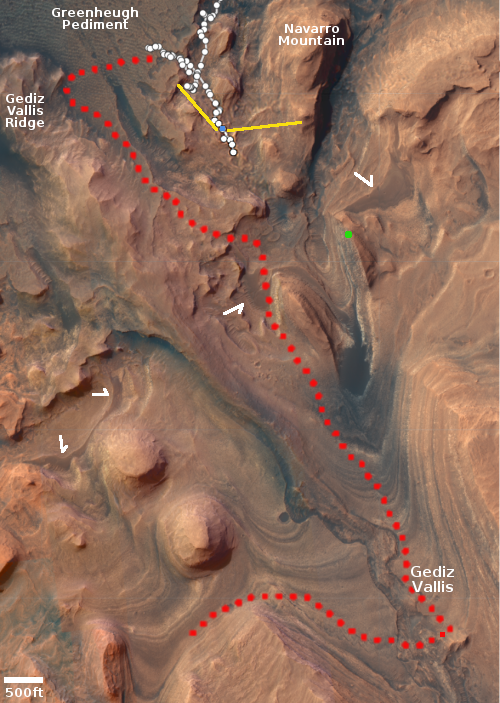

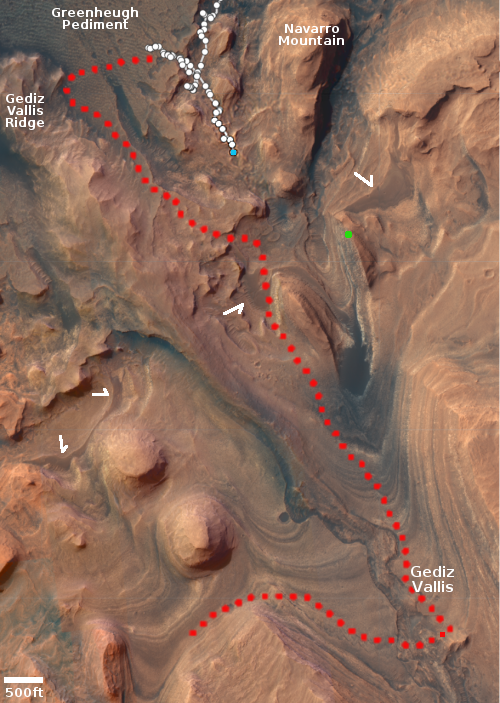

In a press release today, the Curiosity science team provided a major update on the rover’s recent travels in the mountain foothills of Gale Crater.

First and foremost was the new information about the rover’s wheels, which was buried near the bottom of the release:

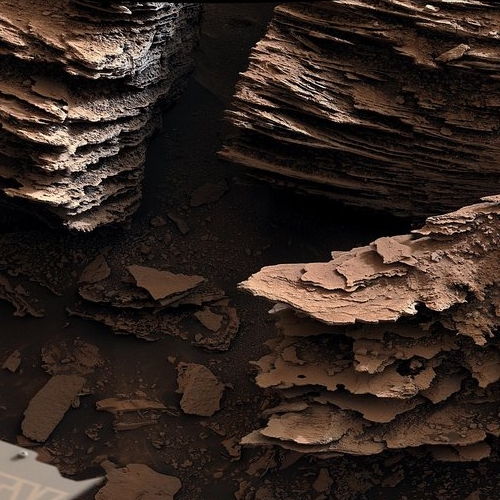

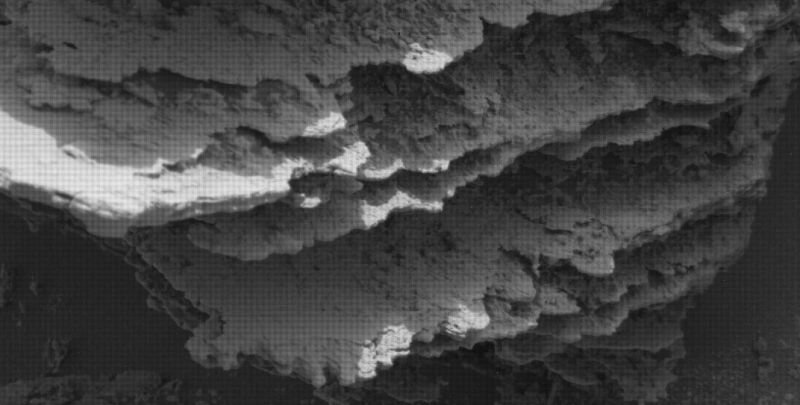

The rover’s aluminum wheels are … showing signs of wear. On June 4, the engineering team commanded Curiosity to take new pictures of its wheels – something it had been doing every 3,281 feet (1,000 meters) to check their overall health. The team discovered that the left middle wheel had damaged one of its grousers, the zig-zagging treads along Curiosity’s wheels. This particular wheel already had four broken grousers, so now five of its 19 grousers are broken.

The previously damaged grousers attracted attention online recently because some of the metal “skin” between them appears to have fallen out of the wheel in the past few months, leaving a gap.

The team has decided to increase its wheel imaging to every 1,640 feet (500 meters) – a return to the original cadence. A traction control algorithm had slowed wheel wear enough to justify increasing the distance between imaging.

In a press release today, the Curiosity science team provided a major update on the rover’s recent travels in the mountain foothills of Gale Crater.

First and foremost was the new information about the rover’s wheels, which was buried near the bottom of the release:

The rover’s aluminum wheels are … showing signs of wear. On June 4, the engineering team commanded Curiosity to take new pictures of its wheels – something it had been doing every 3,281 feet (1,000 meters) to check their overall health. The team discovered that the left middle wheel had damaged one of its grousers, the zig-zagging treads along Curiosity’s wheels. This particular wheel already had four broken grousers, so now five of its 19 grousers are broken.

The previously damaged grousers attracted attention online recently because some of the metal “skin” between them appears to have fallen out of the wheel in the past few months, leaving a gap.

The team has decided to increase its wheel imaging to every 1,640 feet (500 meters) – a return to the original cadence. A traction control algorithm had slowed wheel wear enough to justify increasing the distance between imaging.