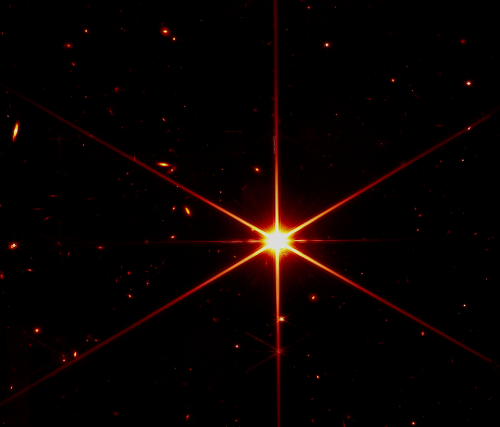

Astronomers think they have detected the most distant star ever

The uncertainty of science: Using the Hubble Space Telescope astronomers now think they have detected the most distant single star ever located, the light of which is estimated to have come from a time only less than a billion years after the Big Bang itself.

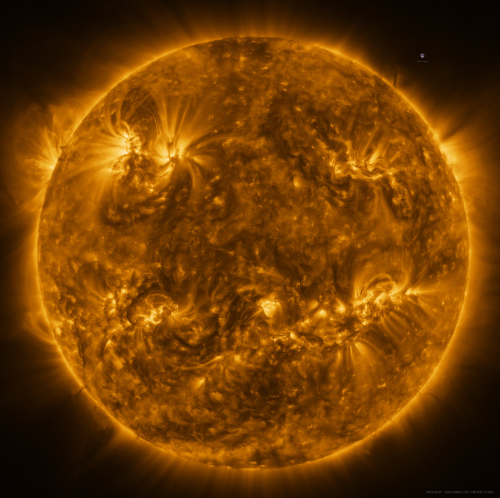

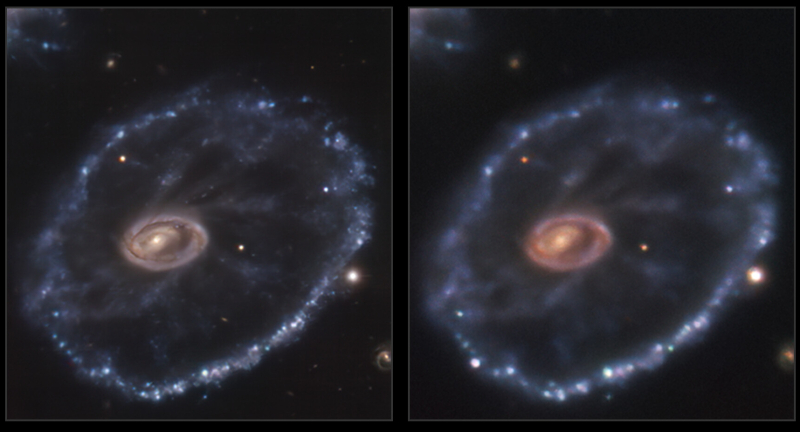

The star, nicknamed Earendel by astronomers, emitted its light within the universe’s first billion years. It’s a significant leap beyond Hubble’s previous distance record, in 2018, when it detected a star at around 4 billion years after the big bang. Hubble got a boost by looking through space warped by the mass of the huge galaxy cluster WHL0137-08, an effect called gravitational lensing. Earendel was aligned on or very near a ripple in the fabric of space created by the cluster’s mass, which magnified its light enough to be detected by Hubble.

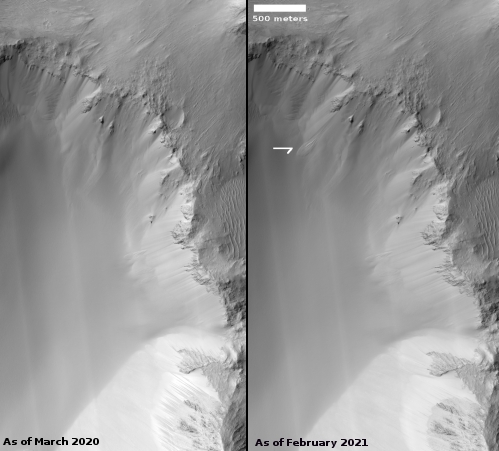

The arrow in the image, cropped and reduced to post here, points to the theorized star. Note the arc that tiny dot lies along. This arc is the result of the gravitational lensing, and illustrates quite bluntly the large uncertainties of this discovery. We are not seeing the star itself, but the distorted light after it passed through the strong gravitational field of the cluster of galaxies. The scientists conclusion that this dot is thus a single star, must be view with great skepticism.

Nonetheless, the data is intriguing, and will certainly be one of the early targets of the James Webb Space Telescope, which could confirm or disprove this hypothesis.

The uncertainty of science: Using the Hubble Space Telescope astronomers now think they have detected the most distant single star ever located, the light of which is estimated to have come from a time only less than a billion years after the Big Bang itself.

The star, nicknamed Earendel by astronomers, emitted its light within the universe’s first billion years. It’s a significant leap beyond Hubble’s previous distance record, in 2018, when it detected a star at around 4 billion years after the big bang. Hubble got a boost by looking through space warped by the mass of the huge galaxy cluster WHL0137-08, an effect called gravitational lensing. Earendel was aligned on or very near a ripple in the fabric of space created by the cluster’s mass, which magnified its light enough to be detected by Hubble.

The arrow in the image, cropped and reduced to post here, points to the theorized star. Note the arc that tiny dot lies along. This arc is the result of the gravitational lensing, and illustrates quite bluntly the large uncertainties of this discovery. We are not seeing the star itself, but the distorted light after it passed through the strong gravitational field of the cluster of galaxies. The scientists conclusion that this dot is thus a single star, must be view with great skepticism.

Nonetheless, the data is intriguing, and will certainly be one of the early targets of the James Webb Space Telescope, which could confirm or disprove this hypothesis.