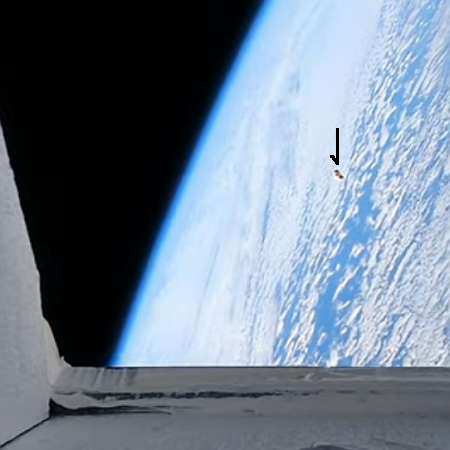

China reports discovery of new microbe on its Tiangong-3 space station

China’s state-run press yesterday announced the discovery of a new microbe on its Tiangong-3 space station that appears designed to survive in the harsh environment of space.

In May 2023, the Shenzhou-15 crew collected surface microbial samples using sterile wipes, preserving them at low temperatures in orbit. Subsequent ground analysis revealed the novel Niallia tiangongensis species, confirmed through multidisciplinary methods including morphological analysis, genome sequencing, phylogenetic studies and metabolic profiling, the CMSA said.

…Niallia tiangongensis demonstrates exceptional stress resistance, maintaining cellular redox balance and ensuring robust growth in extreme conditions by regulating bacillithiol (BSH) biosynthesis to counteract space-induced oxidative stress, according to the CMSA. It exhibits distinctive capabilities in biofilm formation and radiation damage repair, making it a highly adaptable “all-rounder” for space environments.

More information here. This new microbe has characteristics both different and similar to microbes found on ISS. Its discovery is also not that unique, a it appears such unusual and new biology has been found in other space-related environments, such as the clean rooms on Earth used to build spacecraft. For example, dozens were found in clean room for the Phoenix Mars lander in the early 2000s.

China’s state-run press yesterday announced the discovery of a new microbe on its Tiangong-3 space station that appears designed to survive in the harsh environment of space.

In May 2023, the Shenzhou-15 crew collected surface microbial samples using sterile wipes, preserving them at low temperatures in orbit. Subsequent ground analysis revealed the novel Niallia tiangongensis species, confirmed through multidisciplinary methods including morphological analysis, genome sequencing, phylogenetic studies and metabolic profiling, the CMSA said.

…Niallia tiangongensis demonstrates exceptional stress resistance, maintaining cellular redox balance and ensuring robust growth in extreme conditions by regulating bacillithiol (BSH) biosynthesis to counteract space-induced oxidative stress, according to the CMSA. It exhibits distinctive capabilities in biofilm formation and radiation damage repair, making it a highly adaptable “all-rounder” for space environments.

More information here. This new microbe has characteristics both different and similar to microbes found on ISS. Its discovery is also not that unique, a it appears such unusual and new biology has been found in other space-related environments, such as the clean rooms on Earth used to build spacecraft. For example, dozens were found in clean room for the Phoenix Mars lander in the early 2000s.