Sun unleashes strongest solar flare since last solar maximum

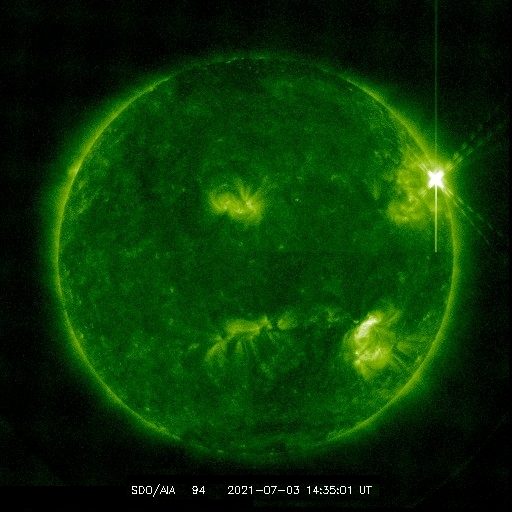

On July 3, 2021 the Sun emitted the first X-class solar flare of the rising present solar maximum, the first such flare since September 2017 during the previous maximum.

This flare is classified as an X1.5-class flare. X-class denotes the most intense flares, while the number provides more information about its strength. An X2 is twice as intense as an X1, an X3 is three times as intense, etc.

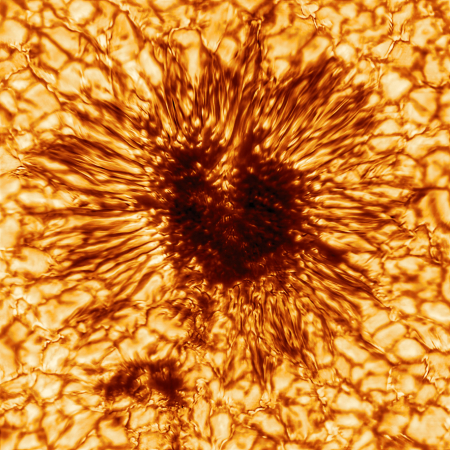

The image to the right was taken by the orbiting Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), designed to monitor the Sun continuously and catch such events.

More information here. The flare caused some disturbances to various radio instruments, though nothing that resulted in any serious consequences.

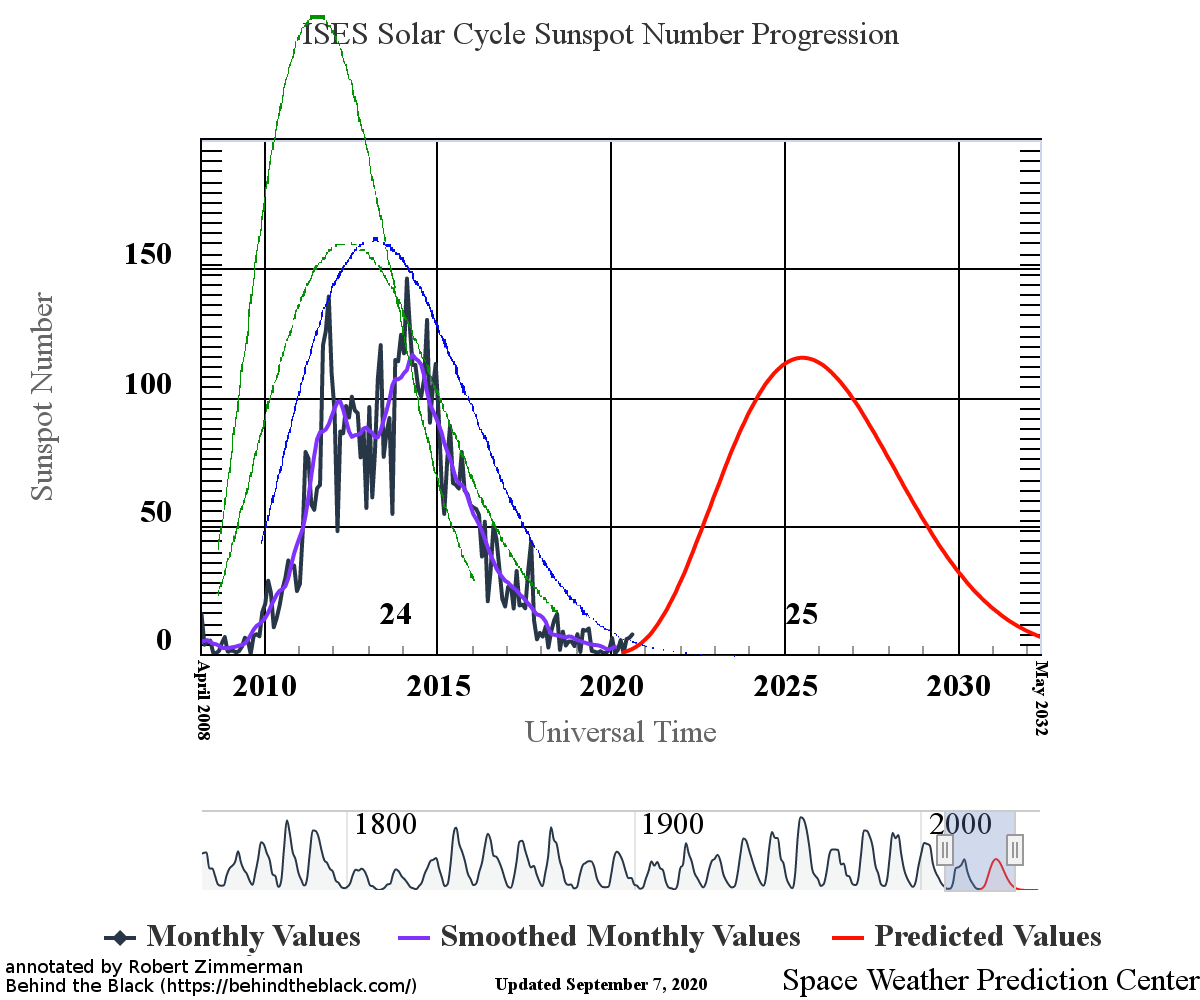

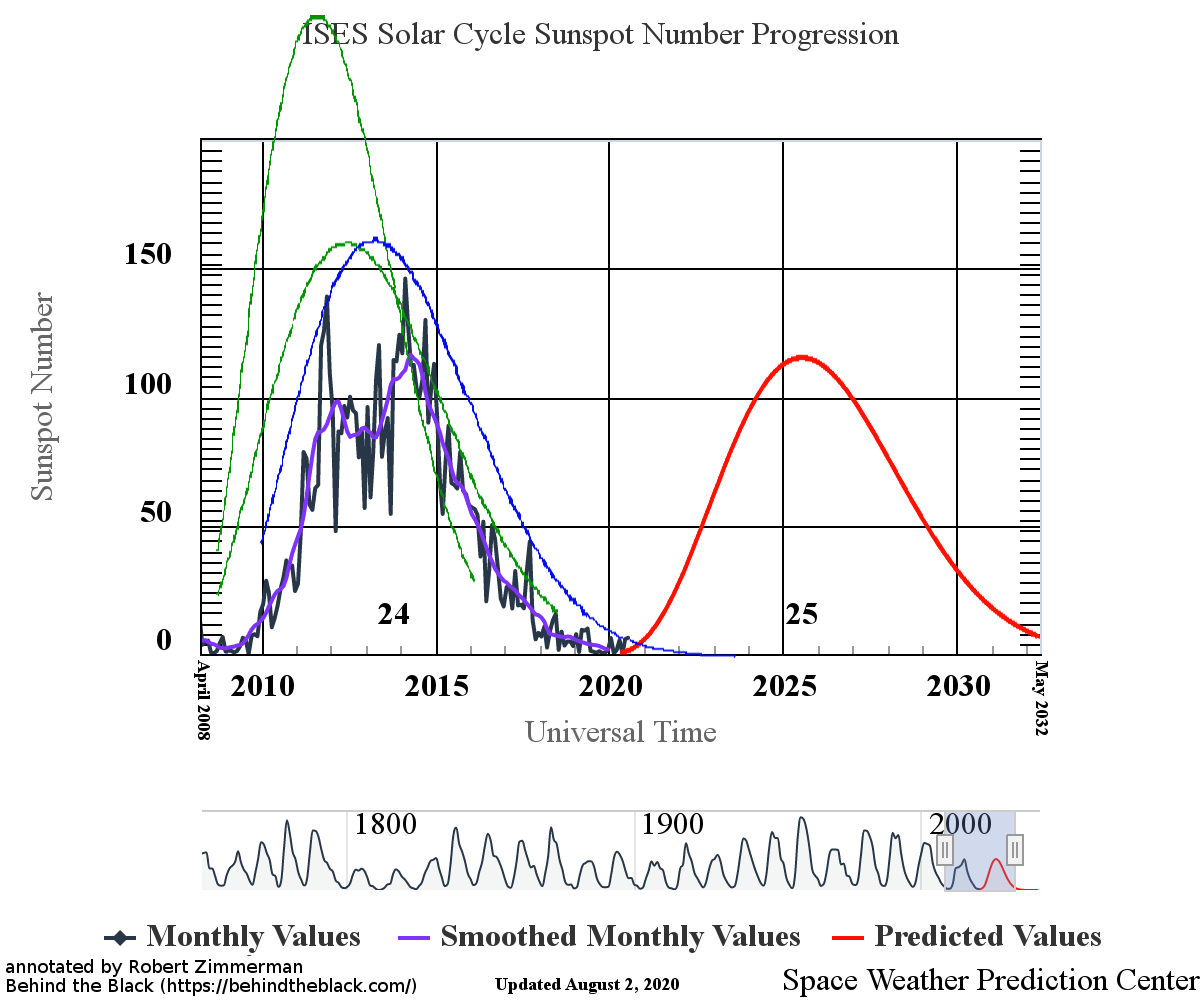

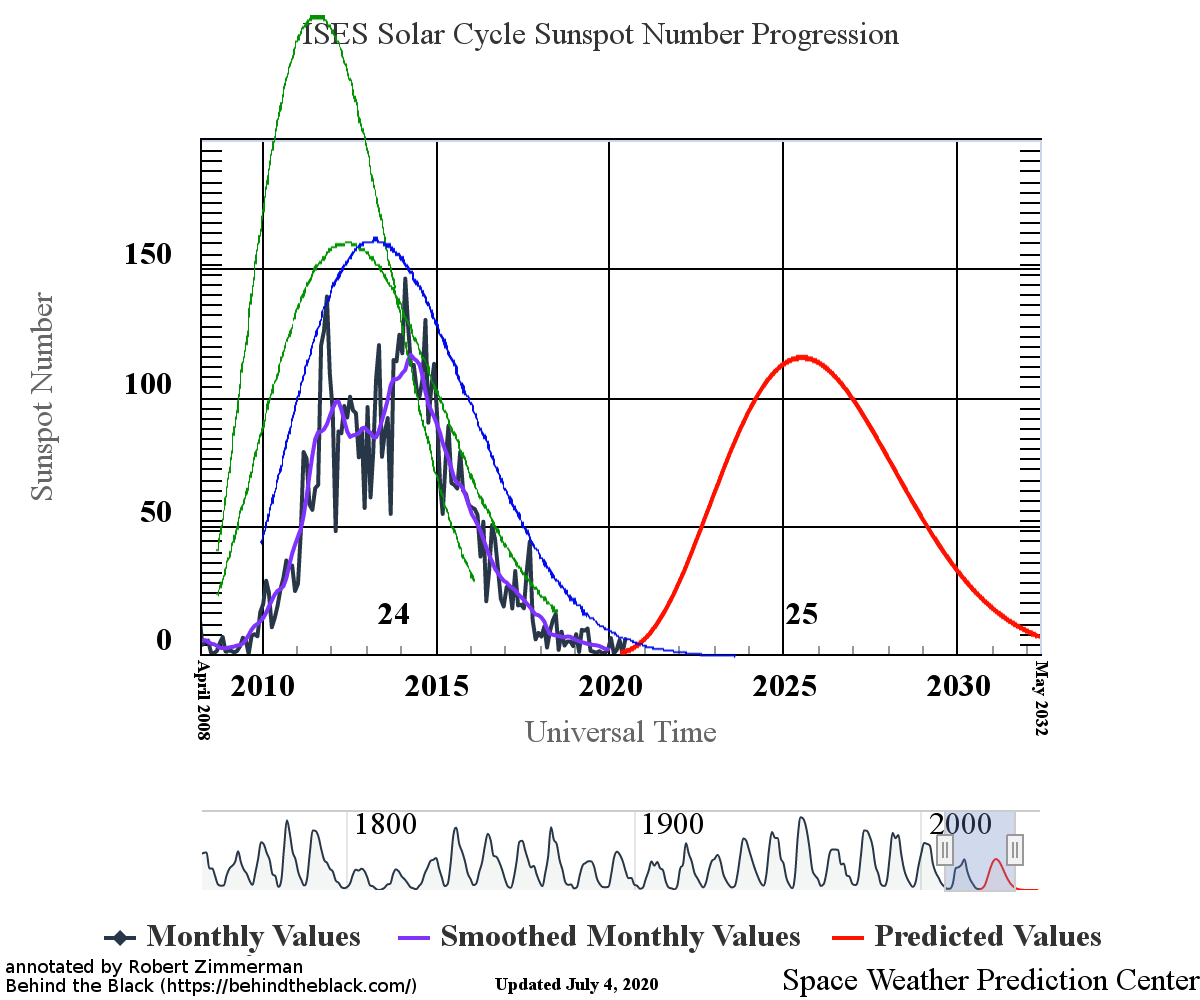

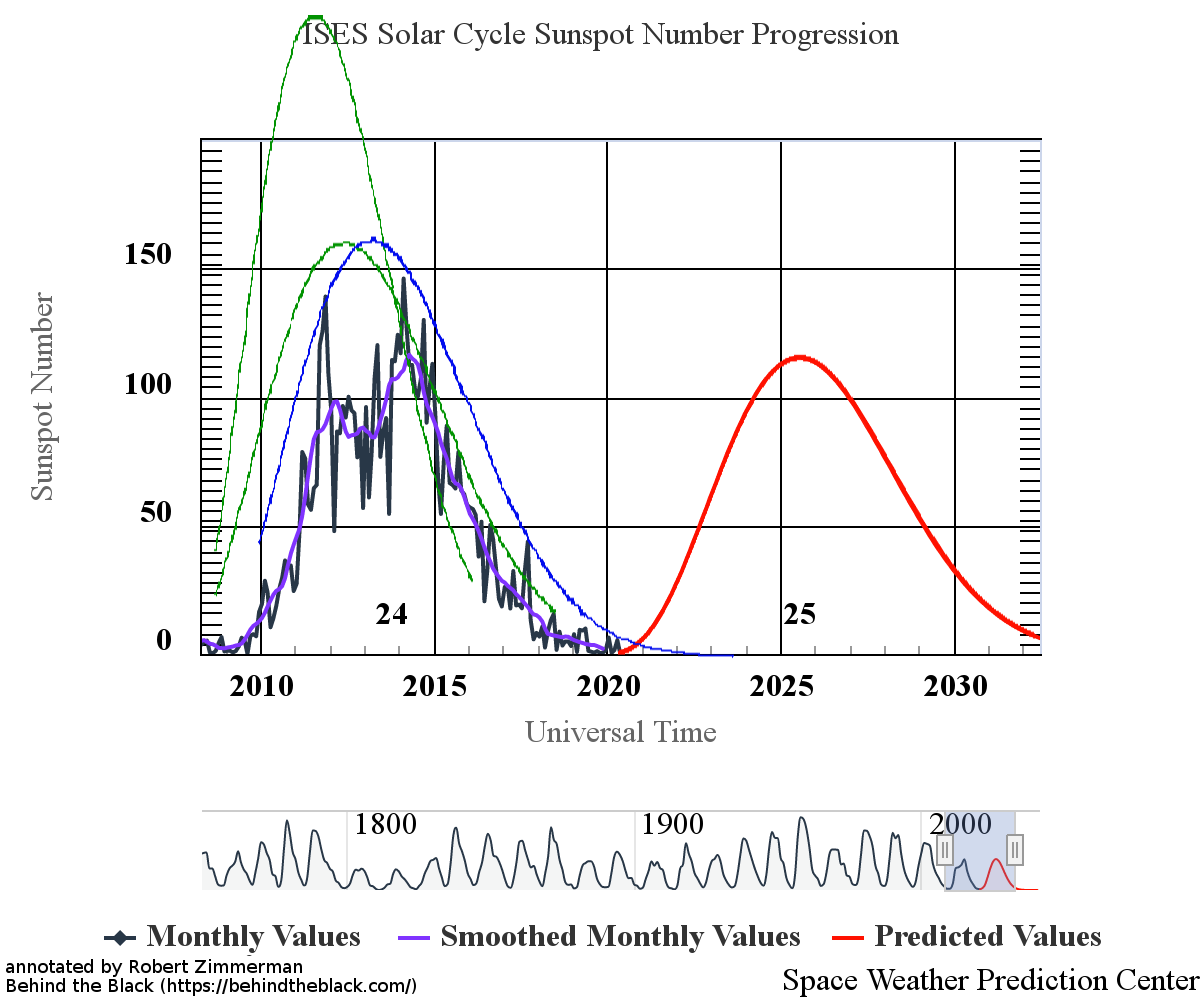

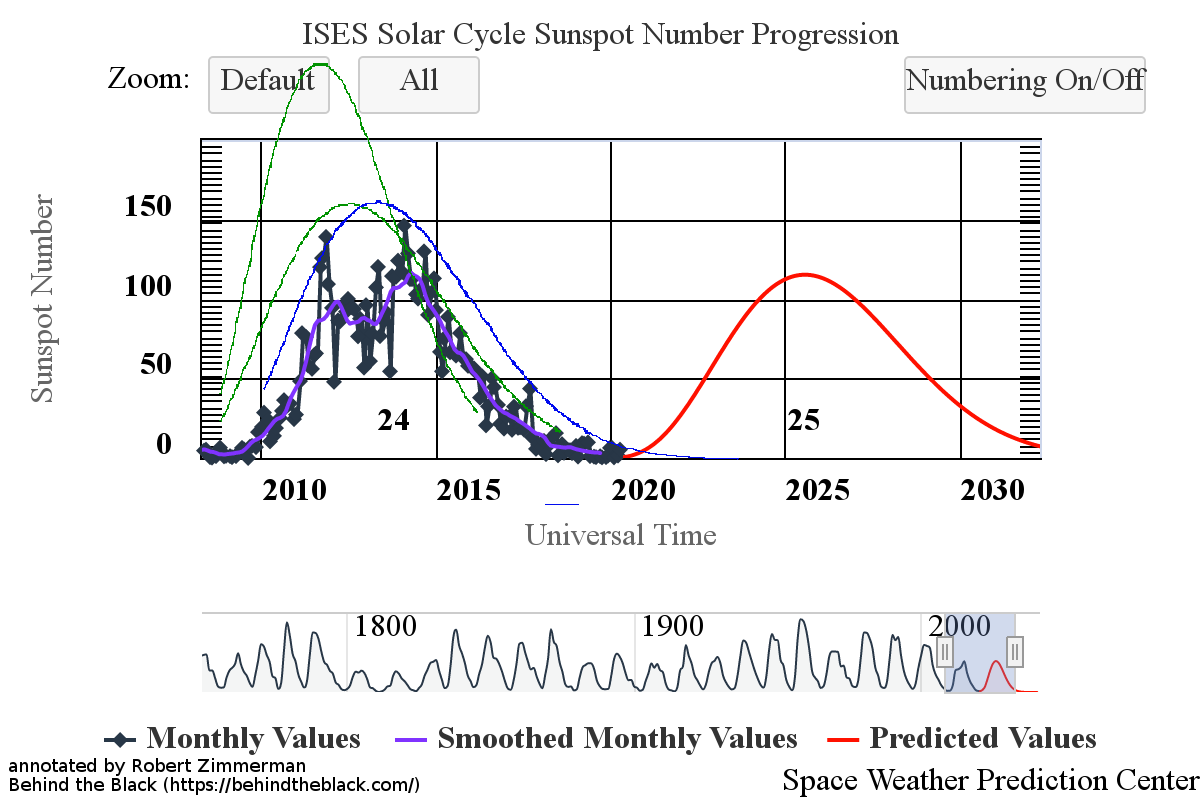

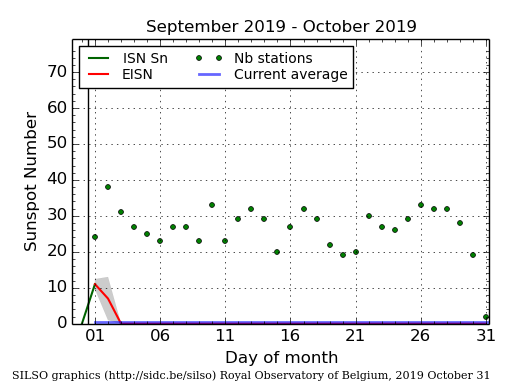

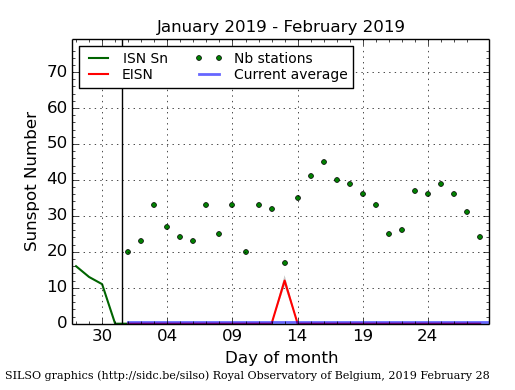

What the flare did demonstrate is that the Sun is definitely ramping up to solar maximum. In fact, the Sun has not been blank, with no sunspots on its facing hemisphere, since May 6th, the longest such stretch since the last solar maximum.

On July 3, 2021 the Sun emitted the first X-class solar flare of the rising present solar maximum, the first such flare since September 2017 during the previous maximum.

This flare is classified as an X1.5-class flare. X-class denotes the most intense flares, while the number provides more information about its strength. An X2 is twice as intense as an X1, an X3 is three times as intense, etc.

The image to the right was taken by the orbiting Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), designed to monitor the Sun continuously and catch such events.

More information here. The flare caused some disturbances to various radio instruments, though nothing that resulted in any serious consequences.

What the flare did demonstrate is that the Sun is definitely ramping up to solar maximum. In fact, the Sun has not been blank, with no sunspots on its facing hemisphere, since May 6th, the longest such stretch since the last solar maximum.