The growing X-ray shell of the 1604 Kepler supernova

Cool image time! Astronomers now have created a short movie from X-ray data compiled by the Chandra X-ray Observatory accumulated during the past quarter century showing the expansion of the cloud ejected from the 1604 supernova discovered by astronomer Johannes Kepler.

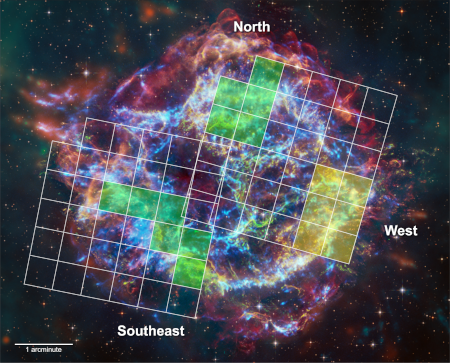

The two images to the right are the first and last frames in the movie. Though they appear the same, if you look closely you will see that in the more recent image the cloud is larger. From the press release:

Supernova remnants, the debris fields left behind after a stellar explosion, often glow strongly in X-ray light because the material has been heated to millions of degrees from the blast. The remnant is located in our galaxy, about 17,000 light-years from Earth, allowing Chandra to make … detailed images of the debris and how it changes with time. This latest video includes its X-ray data from 2000, 2004, 2006, 2014, and 2025. This makes it the longest-spanning video that Chandra has ever released, enabled by Chandra’s longevity. Only Chandra, with its sharp X-ray images and longevity, can see changes like those seen here.

…The researchers used the video to show that the fastest parts of the remnant are traveling at about 13.8 million miles per hour (2% of the speed of light), moving toward the bottom of the image. Meanwhile, the slowest parts are traveling toward the top at about 4 million miles per hour (0.5% of the speed of light). This large difference in speed is because the gas that the remnant is plowing into toward the top of the image is denser than the gas toward the bottom. This gives scientists information about the environments into which this star exploded.

This is one of the curses that astronomers live with. Things take a loooong time to unfold, often several generations. Thus Kepler might see this supernova when it erupts, but the explosion continues for many centuries.

Cool image time! Astronomers now have created a short movie from X-ray data compiled by the Chandra X-ray Observatory accumulated during the past quarter century showing the expansion of the cloud ejected from the 1604 supernova discovered by astronomer Johannes Kepler.

The two images to the right are the first and last frames in the movie. Though they appear the same, if you look closely you will see that in the more recent image the cloud is larger. From the press release:

Supernova remnants, the debris fields left behind after a stellar explosion, often glow strongly in X-ray light because the material has been heated to millions of degrees from the blast. The remnant is located in our galaxy, about 17,000 light-years from Earth, allowing Chandra to make … detailed images of the debris and how it changes with time. This latest video includes its X-ray data from 2000, 2004, 2006, 2014, and 2025. This makes it the longest-spanning video that Chandra has ever released, enabled by Chandra’s longevity. Only Chandra, with its sharp X-ray images and longevity, can see changes like those seen here.

…The researchers used the video to show that the fastest parts of the remnant are traveling at about 13.8 million miles per hour (2% of the speed of light), moving toward the bottom of the image. Meanwhile, the slowest parts are traveling toward the top at about 4 million miles per hour (0.5% of the speed of light). This large difference in speed is because the gas that the remnant is plowing into toward the top of the image is denser than the gas toward the bottom. This gives scientists information about the environments into which this star exploded.

This is one of the curses that astronomers live with. Things take a loooong time to unfold, often several generations. Thus Kepler might see this supernova when it erupts, but the explosion continues for many centuries.