The new in-space repair and refueling industries that are about to revolutionize space exploration

Robots doing work in orbit, as imagined in 1979

When Orbital ATK announced in 2016 that its robotic Mission Extension Vehicle (MEV) — designed to dock with and extend the life of defunct commercial communications satellites — had won its first contract with Intelsat, that contract award only came after several years of persistent campaigning.

In fact, Orbital ATK had had great difficulties getting any satellite communications company interested. At the time, all communication satellites were in geosynchronous orbit, were expensive to build, but lasted routinely from 10 to 15 years. The satellite companies didn’t see a need to fix them when they ran out of fuel. It seems better to launch a new replacement.

Even after winning that contract with Intelsat, it was still four years before that MEV docked with Intelsat’s satellite, bringing it back to life. In the interim Northrop Grumman (which had purchased Orbital ATK in a merger) had managed just one other contract, even as it had announced upgrades to the MEV to allow it to service many satellites, not just one.

The satellite industry seemed in those days to be largely resistant to the concept of repairing and refueling its older satellites.

No more. We are on the cusp of a major revolution in satellite operations, driven first by innovations like the MEV, but accelerated greatly by the new satellite companies launching low orbit constellations. These new companies are willing to take risks, and thus have also shown an eager desire to link their satellites to a variety of in-space services that they themselves did not wish to provide, from satellite repair and refueling to tug services to space junk removal to quick and controlled de-orbit technologies.

The variety and innovation of this new industry is somewhat astonishing, especially considering how young an industry it is.

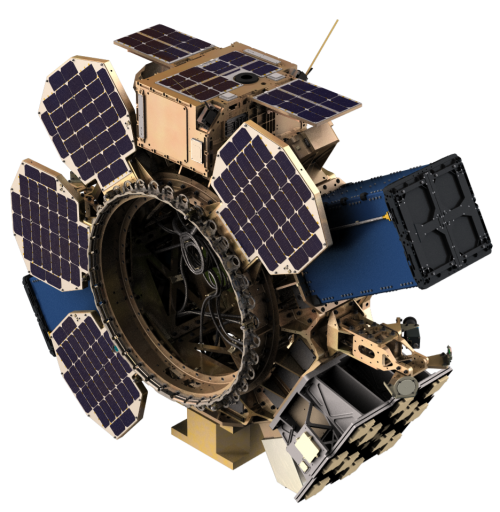

Spaceflight’s Sherpa-AC orbital tug

Orbital Tugs

Much of the drive behind this new industry is the radical change in the nature of the satellites. Previously, commercial satellites had been large, expensive, infrequent, and generally placed in high geosynchronous orbit. Thus, it made more economic sense to build them with their own engines and make then designed to last as long as possible.

The new satellite constellations are generally smallsats, launched in great numbers and placed in low Earth orbit. They don’t last as long, and because they are small it tends to be difficult to provide them with engines to get them to their orbits. Instead, it makes more sense for satellite companies to build their satellites on an assembly line basis, and add engines or tugs provided by other companies.

Already we have several orbital tug companies who have raised significant capital and have actually flown missions. Both Momentus and Spaceflight have each successfully won contracts and have successfully transported satellites for other companies.

Another startup, Launcher, is developing its own orbital tug to be used in conjunction with its orbital rocket. In a sense, Launcher is miniaturizing its upper stage so that it can place different stages on each customer’s smallsat so that those smallsats will be able to get to their own preferred orbit, independently.

Similarly, Rocket Lab has developed its Photon upper stage tug, though that tug has been optimized not to move satellites into ideal Earth orbits but to transport smallsats on interplanetary missions.

Nor is Rocket Lab alone in providing tug services for interplanetary smallsats. The new orbital tug company Impulse Space has signed a deal with the rocket startup Relativity to launch its own probe to Mars. That mission is mostly to highlight its capabilities as an orbital tug company aimed at providing similar services as Momentus, Spaceflight, Launcher, and Rocket Lab.

Though these are all new small startups, the new orbital tug industry is not limited to such companies. Lockheed Martin has proposed building its own orbital tug that would work with a cargo depot to bring cargo to ISS. The cargo depot would simple and cheap to launch, having no engines or thrusters or complex avionics. Instead, Lockheed Martin would launch these complex items only once, on an orbital tug, which would routinely transport the cargo from the depot to ISS. The cargo would reach orbit in a simple cheap way, thus reducing the cost to get it there.

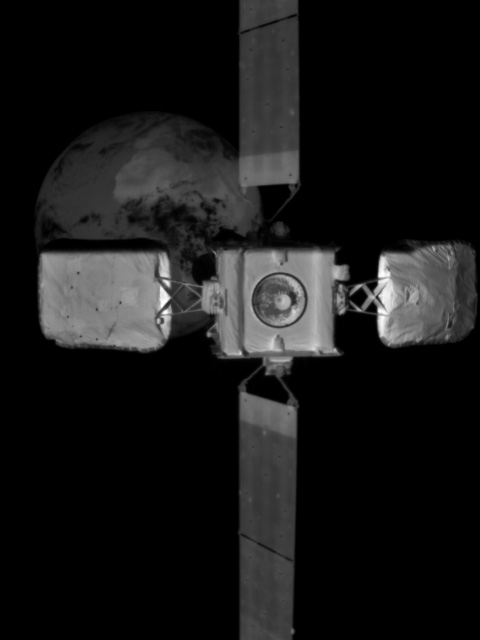

Northrop Grumman’s 2nd MEV’s view, 50 feet

from docking with a defunct Intelsat satellite.

Satellite repair and refueling

While Northrop Grumman’s MEV is already operational, providing new fuel and power to defunct geosynchronous satellites, the company is not alone. Another startup, Orbit Fab, has proposed building a “gas station” in space. This fuel depot would hold hydrazine fuel, generally used by many geosynchronous satellites. An orbital tanker would pick up fuel at the depot and then transport it to the satellite, where it would dock and refuel it.

Meanwhile, Northrop Grumman is now offering an upgraded version of the MEV, called the Mission Robotic Vehicle (MRV). Instead of docking to the defunct satellite, using its nozzle as a docking port — as the MEV did — the MRV will use a robot arm to attach an extension pod. Each MRV will launch with three pods, so that it can fix three different satellites. The MEV was limited to fixing only one satellite.

Northrop Grumman already has six satellite customers signed up for future MRV missions.

Space Junk Removal

All of these tug and repair capabilities are also applicable in some way to the rising need to remove space junk from orbit, as well as efficiently remove defunct satellites when they are no longer fixable.

Leading the effort to remove dead satellites has been the Japanese company Astroscale. It has designed a standard magnetic capture device designed to put on satellites. When the time had arrived to de-orbit it, an Astroscale robot would use that device to grab the satellite and return it to Earth, burning up harmlessly over the ocean. The company already attempted its first test of this design in orbit. Though that test had technical issues, Astroscale subsequently won a contract to de-orbit OneWeb satellites, paid for by the European Space Agency (ESA).

Nor is this the only junk removal contract that ESA has signed. The agency has also signed startup ClearSpace SA to fly a dedicated mission to remove a piece of space junk previously launched, the payload adapter used during a 2013 launch of Arianespace’s Vega rocket.

NASA and the Space Force are also getting into the act. NASA for example has a program to match any investment capital a startup space junk company raises, up to a point. The startup Vestigo, focused on using solar sails to de-orbit space junk, has raised $375K in private investment capital, seed money that NASA has now matched.

The Space Force meanwhile has awarded 125 companies small $250K study contracts for “developing new technologies for the removal of orbiting space junk as well as the robotic servicing of orbiting satellites.”

In announcing the program, Space Force officials noted that they had not expected such a big response.

Gabe Mounce, deputy director of SpaceWERX, noted that when Orbital Prime kicked off in November, it was unclear whether it would attract wide participation. Initially SpaceWERX expected to award 20 to 30 contracts, he said. “What we’re seeing is there’s way more than we thought going into this.”

In other words, there are a lot of space companies out there aggressively pursuing this new field of in-space servicing, many more than the dozen or so I have described above. The Space Force’s program merely revealed how many there are.

This revolution in in-space servicing is going to accelerate the exploration and settlement of the solar system in some most unexpected ways. Not only will these services reduce the cost and risks entailed with orbital operations, the competition to provide these services is going to fuel intense competition and innovation, as each company strives to provide better servicing at lower cost.

The result will be an outburst of development in space, the like of which we have not yet seen.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

Here’s the problem: if you have big orbital antenna farms with huge dishs-add solar panels and new breadboards if you wish. But the Starlink model is that it is easier to just replace an ailing sat in LEO that is supposed to replace all those low-latency assets you want to service.

Yep, and now we have multiple methods being tried. The best approach will be determined by what works, not by the ones who make the best presentation.

I suspect the larger use case for constellations like starlink will be the ability to deorbit dead satellites so that they can put another in its orbit rather than having a gap for years before it’s orbit decays on its own. And if you have a small fleet of essentially vacuum cleaner spacecraft, they may want a fuel depot.

This is an excellent essay, showing that there are business models that thirty years ago we hadn’t thought of. No one imagined them. As business and commercial exploration continue, we should see additional business models that we have yet to imagine.

In the 1950s, Disney and von Braun had imagined space stations and regular space shuttles going to Earth orbit and to the Moon, but we are seeing much more, now that we have more and more people innovating their own ideas into reality.

This is the difference between having one government agency in charge and having 7 billion people in charge. Not only are there more imagineers, there is far more investment money available — and the money is becoming less and less tax dollars and more and more investment capital in which we all can invest and profit from the increased capabilities, products, and improved efficiencies.

I am bursting with anticipation for the next innovations and products that are used in space and that are brought back from space as direct benefits to We the 7 billion people on this good Earth.

There will be satellite piracy.

Suggest a satellite force-projecting body guard for each tug to make it more likely that insurance companies will cover the tugs’ activities.