The up and down tale of two rocket startups, Vector and Phantom

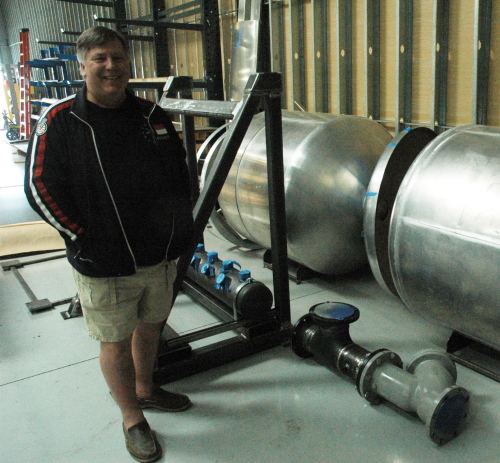

Jim Cantrell at Vector in 2017, shown in front of

one of his side businesses, fixing and refurbishing race

cars and rare luxury sports cars (located then at Vector).

The tales of rocket startups are often fraught with ups and downs of all kinds, often traveling in circles that no one can ever predict. This is one such tale.

In the mid-2010s there was a rocket startup called Vector, based here in Tucson, founded by a guy named Jim Cantrell. At that time Cantrell pushed the company in the style of Elon Musk, going very public for publicity and to raise investment capital.

He was remarkable successful at both. Unfortunately, his engineers were not as successful at engine building. After years of effort they all realized that their rocket engines were under-powered, and wouldn’t be able to get the rocket into orbit. In 2019 the company’s biggest investor backed out, Cantrell left the company, and new owners took over, hoping to rebuild.

Flash forward to 2021, and Jim Cantrell has reappeared with a new rocket company, Phantom Space, also based in Tucson, raising $6 million in seed capital. In the next four years he obtained a small development contract from NASA, completed two more investment rounds raising first $22 million and then around $37 million, and began development of a new orbital rocket, dubbed Daytona. The company also began work on its own small satellite constellation, PhantomCloud (more on this later).

As for Vector, there was little to report during those four years. The only update said the company was buying engines from the rocket engine startup Ursa Major, the same company Phantom was using.

It is now the end of 2025, and the fate of these two companies has once again intertwined, in a most ironic manner. Last week I learned from Jim Cantrell that Vector had closed shop, and that its last remaining assets, some of which Cantrell himself had helped develop when he headed Vector, had been bought by Phantom. This includes several unused rocket stages, the vertical rocket test stands, a lot of computers, and hardware.

Cantrell himself drove out to California, packed up the stuff, and shipped it back to Tucson. The picture to the right shows one truck with an unused Vector rocket stage sticking out the back.

Meanwhile, Phantom seems quite alive, though as with all startups things are taking far longer than planned. It is not going to launch Daytona in 2023, as first predicted by Cantrell to me in 2022. Nor will they do it in 2026, as Cantrell later predicted in 2024. Now the company hopes to do its first static fire tests in ’26 (using engines built by Ursa Major and Vast’s Launcher engine subsidiary), with a launch targeting the second quarter of 2027. No one should be surprised if the company doesn’t meet these dates either.

The company however appears sound. After raising $37 million in 2024, it is now planning another round of fund-raising in ’26, aiming to raise $60 million. Both of its launchpads at Cape Canaveral in Florida and Vandenberg in California are under development. At Cape Canaveral that launch site is the landing pad SpaceX presently uses for Falcon 9 landings, and Phantom is negotiating a lease with SpaceX to let it continue to do landings there, as long as they do not conflict with Phantom launches.

And the company is taking a page from SpaceX and developing its own satellite constellation to launch on its own rockets. Unlike Starlink, however, PhantomCloud is not for internet communications, but will be a large constellation of smallsats acting as orbital data centers (ODCs) for cloud computing.

Now, I expect the mention of ODCs will cause the eyes of many of my knowledgeable readers to roll in skepticism. In the past six months practically every satellite, space station, orbital capsule, and rocket company (including Musk) has been raving about this idea: It’s the new hot thing! Put your cloud data centers in orbit rather than on Earth! We can do it for you!

Most of these promises and claims are hogwash, and should be treated with great skepticism. Many are being pushed by people who know little about space, and thus don’t know the complexities of building a satellite. We can be sure most will never get off the ground, or will fail if they do. At this point we don’t even know for sure if the demand for such things really reflects a true market, or a bubble of false enthusiasm.

Jim Cantrell at Phantom in 2022.

What makes Phantom’s constellation different is threefold. First, Cantrell isn’t jumping on the bandwagon here. The bandwagon is trying to catch up with him. He first mentioned this idea to me in 2017, while giving me a tour of Vector. In the interim he obtained patents for the idea, in a manner that will require a lot of the new proposals by others to come to him to get licensing rights.

Second, many of the new ODC proposals involve large satellites. Cantrell’s proposal is aimed at putting up many smallsats distributed in low Earth orbit. SpaceX hopes to do the same thing using Starlink as its base, but I wonder if it might also be need to work out some license issues with Phantom first.

Third, Cantrell is not coming to this project as a novice. He has spent years working on spacecraft, including some planetary probes.

Phantom has been developing this concept now for several years, putting it well ahead of the herd. It is building two demo satellites for launch late in 2026, setting the stage for constellation deployment thereafter. If Daytona develops even close to schedule, the company will be well positioned to not only build its satellites, but eventually launch them. SpaceX has already proved the synergy of that arrangement.

Most importantly, it is also well positioned to put its ODC constellation up before anyone else.

All this remains the stuff of dreams, however, except that those dreams do involve real satellites and rockets being built. The dreams will only become reality when they finally get launched. And I have been following Jim Cantrell’s story now for almost a decade, and he still hasn’t launched anything. While we all wish him well, we also must remember that this is rocket science. It ain’t easy, and there are never any guarantees.

Only the future knows what will happen.

————–

Full disclosure: Jim Cantrell has long been one of the biggest supporters of my work here at Behind the Black. He has also never tried to tell me what to write. If he had I would have returned his donations.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

Hoping Jim can get Phantom flying. I’ve been waiting on the rocket for a few years now. Bought flights on other birds in the meantime but I do see their plan and want them to succeed.

Usually it is disgusted engineers underfunded and imposed upon by suits….pre-Limp Blue Origin, for instance.

Here it looks like the money-man was surrounded by folks in over their depths. This is the reality of most New Space…Elon a rare exception who was good either side of the ledger.

I want you guys to put your politics aside just for a moment and listen to an individual who is most assuredly not lazy:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=3-qin4oRhA0&pp=ugUHEgVlbi1VUw%3D%3D

The question I have is this.

Was America better off before Reagan, when we had living wages and strong unions like how my Dad was able to support a family, cars and house with one income?

Or are we better off after Reagan when everyone works two jobs and are still poor.

When labor is not respected, things fall apart.

Jeff, you’ve got a few things backwards. Listened to a few minutes of your link to see if there was anything valid or new. That would be a negative. His theme being young people don’t want to work for a company that doesn’t care about them personally is an age old situation. The difference now being that young people, and many older ones, think they should be able to live like the TV show sitcom actors that support a good lifestyle with a half ass job. That’s never been true in reality.

If you think living was better 50 years ago, you have to either be young or have a bad memory. The one income household legend for instance skips lower standard of living. To quote one economist, “poor fat people are a new phenomenon.” Unions were mostly good for the members at the expense of nonmembers until their greed killed their company, and sometimes their industry.

I know you are just having fun here and it shouldn’t bother me. Once in a while though, the blatant lie will get rhrough to me.

Jeff Wright asked: “The question I have is this. Was America better off before Reagan, when we had living wages and strong unions like how my Dad was able to support a family, cars and house with one income?”

The question that I hear Jeff ask is: Was America better off in the days of free market capitalism, or is it better off with the increasing marxism and centralized control that we have now?

Reagan is a red herring, because he was unable to move the country back toward smaller government and more individual freedom. He reduced taxes, but that only increased revenue, which, rather than pay-down that national debt, the Democratically controlled Congress spent, and then some, continuing the deficit spending and continuously increasing national debt that had begun under Carter.

john hare is correct that the unions put themselves out of business. They emphasized higher pay and benefits to the exclusion of such business matters as quality and profit. Without profit, owners had no reason to continue investment in their companies to expand. Ironically, about the time of Reagan, the unions championed offshoring some manufacturing and using foreign suppliers, reasoning that when those countries increase their populations’ incomes then those people would also buy American goods made by USA union workers. It didn’t work out that way, however.

Instead, the foreign companies were able to make their products for lower costs, because they didn’t have to pay union wages or overblown benefits, and the foreign governments’ regulations were not overbearing. America lost its ability to make union goods. Even Hollywood studios and filmmakers use foreign locations because of the lower costs; even hiring foreign translators for foreign crew direction is cheaper than the Hollywood unions.

So, no. We are not better off under the increasing marxism in America. Americans once had jobs to go to that were substantial and full time, but now companies pay so much for minimum wages that they cannot afford to hire full-time inexperienced people, so those who still need to earn their experience are reduced to multiple part-time jobs. What a disaster marxist, centrally controlled, overregulation has done to us.

The marxists have even made terrible changes to our society and culture. Despite the much greater inequality that we used to have before the Civil Rights Act, there are people who honestly believe that the entirety of America is now more racist than the systemic racism of the Jim Crow South, before the Act. When Obama was elected, Democrats and the American press believed that we were finally entering a post-racial America, but in his own marxist way he promoted the idea that America was even more racist than before the country elected a black man as president. Somehow, that election is declared by marxists as proof of racism, not evidence that we had recovered from racism.

So, no. We are not better off under the increasing marxism in America. We were better off before. At the very least, before the Civil Rights Act we could identify actual racism and we could do something real about it, but now that racism is a feeling rather than a fact, it is difficult to eliminate the feeling, because facts no longer matter in why someone feels the way they feel. When they feel like victims of racism, they no longer try to get a job or to get an education, and lacking these they feel even more justified on feeling like racism is worse in America.

Marxists have increased stupidity in America. Not only do many governments in America act as though a boy can be a girl, but marxists are no longer able to define what a woman is — to the point that we now have a Supreme Court Justice who is so incapable, too stupid to provide a definition that a three-year-old can provide.

So, no. We are not better off under the increasing marxism in America. We were better off before we were carefully taught to be stupid.

Reagan made a deal that reduced illegal immigration, for a while, but today we have just finished a rush for illegal aliens to enter the U.S. and suck off our government largess, costing us hundreds of billions of dollars in unnecessary welfare payments, hundreds of thousands of children lost inside our country, and riots and insurrection when our immigration laws are enforced. We are another step closer to the marxist concept put forward by Cloward–Piven strategy to cause such costs to the government that it fails from the confusion and debt, transforming into an even deeper marxist government that takes from the workers and gives to the “needy” non-workers with a guaranteed minimum income — an income for not working or for not being productive — destroying free market capitalism. I’m sure that was what Obama had thought would happen when he said that his followers were only days away from fundamentally transforming America.

As Milton Friedman once said, you can’t have both open borders and a welfare state. Marxists created the welfare state, post-Reagan, and marxists opened our boarders, again post Reagan. The Minnesota Somalis are showing a growing amount of massive corruption in America.

Unfortunately for him, and fortunately for the rest of us, free market capitalism and freedom are strong enough to survive a lot of heavy damage, to the point that new small rocket launch companies are still able to raise money and survive long enough to start operations. Marxism has shown us that it is not able to survive even when applied as intended.

So, no. Despite being a strong system, free market capitalism and our way of life have been badly damaged by the post-Reagan marxism that has been imposed upon America, leading to people asking such stupid questions as whether we are better off under pre-Reagan freedom or post-Reagan marxism, thinking that it was Reagan, not marxism, that has damaged the country, the economy and the society.

Just remember that the guy I linked to is your typical swing voter.

Go after him at your peril.

A reasonable analysis of the standard of living over the last half century is that it has constantly improved for the majority. Most of what is considered middle class now have a lifestyle that would have been reserved for the quite wealthy just a few decades back. This is in spite of government and unions, not because of. Virtually every physical improvement has been by businessmen acting in their own self interest, though that interest is not simply money for moneys sake for the most part. A vision of better shopping or communications or rocket launch or package delivery must precede the revenue for such but requires that money to execute on that vision. Money alone is a means to an end.

The problems we face are quite real and will have to be addressed. The first part to be addressed is the accurate understanding of the problem. A simplistic blame on Democrats, unions, immigrants, Rinos, politicians, the young, the old, China, etc, etc only obscures the actual problems that need to be faced. Name calling doesn’t get the job done. For example MSFC has been condemned by some and said to not get enough love by others. A quick search reveals that MSFC budget runs about $4B-$5B per year. That should buy a lot of love, or more accurately, prostitution. Why that level of spending on a non-performing sector needs understanding. Short answer is vote buying. Longer answer is embedded in the political system in place.

The political system in place in the US rewards pork with votes. Until those incentives are addressed, improvements will not happen. It is not a matter of educating the voters. The voters are going to vote mostly in their perceived self interest. A politician must convince those voters that they will be better off with him or her than the other politician. Puts them in the trap of promising whatever it takes to get elected since failure to get elected means that their platform is functionally irrelevant as they have no power to execute.

Want illegal immigration stopped. Very simple. Make it legal for working people to come here and contribute to our economy and the ones that remain illegal are most likely actual criminals to be dealt with. Worried about the strain on the welfare system from immigrants, eliminate the welfare system entirely. The deadweight loss from welfare being gone would free up charity resources more than sufficient. Ask why that is politically infeasible and you are most of the way to solving that problem

Think people don’t want to work for a faceless corporation. Simple if they can either find a way to produce something of value to others or starve. Or they can turn to crime and get shot as it makes no sense to spend billions warehousing people that are predators by preference. Worried about the homeless. Make it legal to rent rooms by the day and to build appropriate housing. Make it legal to hire them at wages appropriate to their productivity.

Most gloom and doomers don’t seem to understand fairly recent history. Single wide mobile homes were a step up for many people within living memory. Groceries are quite affordable compared to when I was young. Clothes are affordable if you don’t do designer status crap. The problems with insurance, housing, and medical care can be addressed at the individual level, but not if one insists on the gold plan. I live in a small house that I designed to be fire and storm resistant. Being paid for, the insurance company can go jump. Medical benefits from attention to prevention.

That there are a lot of problems that really need solving should not obscure that the physical means to solve them are at an all time high. I could go on for pages, but Robert may already find it necessary to delete this comment.

SLS is going to put that “nonperformance” lie sooner than Lunar Starship flies.

It has to exist first before I can even call it garbage.

Jeff Wright

“”””January 1, 2026 at 3:08 am

SLS is going to put that “nonperformance” lie sooner than Lunar Starship flies.

It has to exist first before I can even call it garbage.”””

The difference is that it is the taxpayer getting screwed by that SLS prostitute. Whether Starship succeeds or fails, the taxpayers hemorrhoids are safe.

Jeff Wright,

Unions in heavy industry didn’t have much to do with improving living standards. Most of US heavy industry was unionized by the 1930s but the Great Depression had a lot more influence on living standards than unions did. What raised living standards was not unionism but WW2 and the temporary US near-monopoly on manufacturing following that war. As war devastation receded in Europe and Japan and formerly pastoral nations industrialized, the US lost that near-monopoly. It was pretty much gone by the mid-60s.

Unions were already declining by then because their fundamental pitch was false – unions could not get perpetual above-market wages for their memberships by threatening strikes. All they did was stagnate the industries they dominated. In the ’50s, most of the Fortune 500, especially the upper ranks of it, were unionized. Starting in the ’70s, more and more of the unionized former top-rankers on that list slipped down the rankings and were replaced by newer companies in newer industries that were not unionized. That has continued right down to the present day.

A union is, at its core, a protection racket with a government license. There’s a reason for the long association between organized labor and organized crime – the former is, in essence, a subset of the latter. I still remember the days when the Teamsters Central States Pension Fund was pretty much the venture capital arm of the Mafia.

As with most types of over-successful parasites, unions eventually kill their hosts. When that happens, of course, the cushy pension benefits instantly disappear and all of the saps who paid dues all of those years get only whatever pittance the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation chooses to settle on them. The PBGC has probably the most Orwellian name of any US government agency as “guaranteeing” pensions is exactly what it does not do.

The stagnation of “middle class” wages didn’t start with Reagan, it started in the early ’70s when we Baby Boomers hit the labor market and flooded it. The effect was even greater than it would otherwise have been because women were also entering the labor force in large numbers for the first time since the Rosie the Riveter days of WW2 and the combined onslaught tanked wages for everyone. Sometimes there are no villains, just large secular forces of economics and demographics at work.