Who was Cornelius Vanderbilt?

I ask the question in my headline because I am quite sure it is a question most Americans can no longer answer, with any firm knowledge. I myself didn’t know who Vanderbilt really was until I read a wonderful biography of him, The First Tycoon: The epic life of Cornelius Vanderbilt by T.J. Stiles, about two months ago.

Beforehand, all I really knew about Vanderbilt was that he had been a big deal somehow in the 1800s, and as a result there was a statue of him on the south side of Grand Central Station in New York, visible only by drivers going past on the overpass that circles the station.

What I learned from Stiles book however was astonishing. Not only did Vanderbilt build Grand Central Station, it was part of a transportation empire he created that by the end of his life covered most of the eastern United States. For Americans in the 1800s, if you needed to get from one place to another, you almost certainly rode on a Vanderbilt steamship or railroad.

Even more interesting to me however were the remarkable similarities in style, approach, and success between the Cornelius Vanderbilt of the 1800s and the Elon Musk of the 2000s. Both focused on taking new technology and making it profitable. Both built their empires on transportation.

And most of all, both focused on the product they were building to make money, not on speculating its value to make a quick buck.

Vanderbilt’s statue in front of Grand

Central Station. Click for source.

In Vanderbilt’s case, he began as a teenager growing up in Staten Island working on his father’s sailing boats. Much of their income came from transporting commuters to and from Manhattan. Vanderbilt soon expanded the business with his own boats. When steamships arrived he quickly transitioned to that new technology, establishing commuter lines all along the waterways from New York to Philadelphia to Boston to Albany. The Staten Island Ferry for example was created by Vanderbilt, not the New York City government.

As this business grew he linked it with ground transportation, first wagons, then railroads. Railroads required gigantic amounts of capital, and thus forced the establishment of the first large corporations, using stock sales to raise that capital. Not surprisingly, many railroad executives saw the manipulation of the railroad stock as their prime method of getting rich. They didn’t care if they ran their railroad into the ground, and in fact, often did exactly that, if it allowed them to cash in.

Vanderbilt was different. When he financed a new railroad, or purchased its stock, it wasn’t to speculate on the stock. It was to make that railroad a profitable operation, serving its customers with reasonable fares while getting them where they wanted to go as quickly as possible. Often he gained control of one of those badly run lines and quickly reorganized it, making it profitable once again.

And in this task Vanderbilt was remarkably successful. By the time he died in 1877 he was the richest man in America, his wealth so large it was difficult at that time to measure it. His railroads provided the main transportation from Chicago across the entire northeast of the United States.

Vanderbilt’s story was even more fascinating to me because of its uncanny parallels with that of Elon Musk. Like Vanderbilt, Musk started small, but at every step used new technology to create products needed by the general public. First it was Paypal, then it was SpaceX and rocketry. Next it was electric cars, followed by large scale municipal tunnel digging and robots.

In every case however Musk has had no interest in speculation. His goal was to make a good product, one that people wanted to buy because it provided what they needed at less cost than his competitors while doing it better.

And like Vanderbilt, Musk built his empire based on the American concept of freedom and capitalism. The goal was to make money, creating new products. The route to do so was through each man’s personal creativity, following his own personal dreams.

In the 1800s Vanderbilt was largely free to do whatever he wanted. The government had little regulatory control of his actions. His general honesty, combined with a ruthless competitive spirit, resulted in great success.

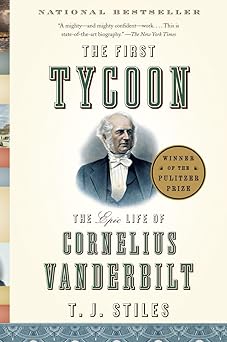

Musk entering Twitter headquarters for the first time,

carrying a kitchen sink. His message: I’m cleaning house!

In the 2000s Musk has not had as free a hand as Vanderbilt. Our modern administrative state controls too much of American business. Musk has either had to feed off its trough, or fight it tooth and nail to get it out of his way. For Tesla he relied on government subsidies. With SpaceX he had to sue the Air Force to allow it to bid on military launch contracts. With Starship he had to become political to kick the Democrats controlling the White House out of power, because their red tape during the Biden years was suffocating him.

And when Twitter was squelching the free speech of conservatives, Musk simply bought it and reshaped it to do its job right, making X now one of the best bastion’s of free speech in the technological world.

But like Vanderbilt, Musk has no interest in political power. Vanderbilt always avoided politics, at all costs. The only time he involved himself in Washington was during the Civil War, when he donated his largest ship to the Union effort. As Stiles noted,

An honest reading of the evidence shows a proud, prickly, and highly capable man of immense personal force–one who was also deeply patriotic. … When given the chance, he served his country to the utmost while refusing any remuneration.

One could easily apply this description quite accurately to Elon Musk. He didn’t campaign for Trump because he hoped it would win him government contracts. He did it because he saw Trump as the best option for America. That it might help his own businesses was of course likely, but that possibility was clearly not Musk’s prime motive during last year’s election campaign.

And once that campaign was over? Like Vanderbilt, Musk abandoned politics to go back to his private businesses.

Vanderbilt’s history, as well as Musk’s, illustrates the greatest aspect of America. It truly is a place that supports “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” You certainly can do bad things with that freedom, but if you make morality and doing good works as your fundamental goals, that freedom will allow you to do great things.

Vanderbilt, and Musk, prove this. We would be wise if we all emulated them.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

I’ve thought long and hard about trying to identify a 19th century equivalent to Elon Musk, either in Britain or America. And I haven’t found anyone who quite fits the bill.

But there are a handful of men who anticipate certain aspects of Elon in different ways. Cornelius Vanderbilt is most certainly one of them. He was a great American success story, one who contributed in a very meaningful way to America’s success, too. He deserves to be remembered more than he is.

Brunel’s Great Eastern was the Starship of its day and then some….but that ship was based on the opposite of “the best part is no part” since it had paddlewheels propellors and sails…so more B-36, I suppose.

People had no fear of size then… something space launch had an issue with until recently.

For the longest time in the USA, our philosophy was to miniaturize the payload. The Soviet Chief Designers were actually closer to Brunel in that their approach was “make the rocket bigger.”

R-7 was the result…and now available as an Estes rocket.

To this day, there are folks even in NewSpace that still balk at the SHLLV concept.

Now while I must have my little jokes at Elon’s expense from time to time, I truly appreciate the fact that he understands the need for LV growth.

Trucks, ships and planes have increased in size–but for the longest time, rockets stayed in the Delta family payload range.

This small-mindedness still lives in the heads of many… something hard for Brunel and Elon to overcome.

Vanderbilt was perhaps more of a Warren Buffet of his age, with Brunel more of a visionary like Musk.

I think Brunel was the most brilliant engineer of the 19th century (and I am not alone in thinking this!), but I think the problem he ran into with Great Eastern is that he was entering a transportation field (maritime steam propulsion) that was much less mature in 1854 than orbital rocketry was in 2002. Worse, he went in “big,” with the largest vessel ever built, so the risk was even higher. The immaturity of that technology meant that he felt compelled to use two propulsion systems (one screw propeller and two paddle wheels), and using sails as auxiliary power, which was common practice at that time with sea-going steam vessels.* No one had ever made twin screws work consistently yet, let alone at scale.

I think he would have worked it out with screw propulsion even after Great Eastern failed, but his tobacco habit cut his life tragically short before he had the chance.

* For context, the US Navy and Britain’s Royal Navy were just starting to get seriously into steam propulsion at this point in time; but warships which they had built or converted to have steam power plants all used single screws, and they only used the screws as *auxiliary* propulsion, with sailpower still their mainstays. With Great Eastern, it was the other way around.

Prof Tom Woods

“The (Myth of) the Robber Barons and the Progressive Era”

Mises Media (2014)

https://youtu.be/-VA9VZeox3g

1:00:00

“Unless you were home-schooled, you were taught to hate these men based on dubious economic theories expounded by so-called experts who all hated capitalism.”

The Men Who Built America

“A New War Begins” Se 1 Ep 1

https://youtu.be/WwyQTaab8J4

1:26:32

“Out of the turmoil of the Civil War, America enters an age of enlightenment that will change the landscape of the country. The growth is driven by five insightful men who will change the world forever.”

To Wayne

I despise the one thing railroad barons were praised for—over-extensive parks

https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2017/08/10/railroad-magnates-philanthropists-helped-launch-our-national-parks.

The Audubon types thought it was great–but we need resources locked up away from industry.

It is like Nixon going to China…the one thing he did that met with approval to me is the worst thing he did.

I didn’t care a jot about Watergate. Instead of lying to protect his friends–Clinton had his friends lie to protect himself

Jeff–

Railroads and National Parks– complex history.

“Robber Barrons,”– the Name is loaded to begin with.

Yellowstone was the first park in 1872, then we get a few in the 1890’s, turn-o-century the floodgates were open on “national parks.”

Vanderbilt dies in 1877.

-Railroads were in the process of being over-built when Vanderbilt built his rail empire, and to Robert’s point in his comments, rather than shutter good rail he was determined to find more cargo to fill all his trains. (and then we get JD Rockefeller shipping kerosine by rail which fills the bill until he squeezes Vanderbilt et al by building oil pipelines and by-passing the railroads.)

-National Parks and railroad tourism:

That’s more of a “western thing,'” and I can’t speak too deeply on that, other than to note that the

only cross-country route (of 3) that was constructed without government subsidy, was the Empire Builder route (JHill,)

———-

We do not have a Carnegie Library in my town, only because our Local Lumber Barron(s) had already donated a Library, Hospital, and a School. The town adjacent, does have a Carnegie Library, and their “Local Fruit Barrons” donated the Hospital.

————

Rockefeller court speech

from The Men Who Built America

https://youtu.be/DBrz57sNAc4

2:41

“You call it monopoly; I call it Commerce.”

Thanks for pointing to “The (Myth of) the Robber Barons and the Progressive Era”. That book is a must read.

Richard M,

I think there is not a single 19th-century figure comparable to Elon Musk. Combine Vanderbilt with Edison and you’d at least be in the neighborhood, though you would still be short of the mark.

I don’t think Brunel was the greatest engineer of the 19th century. I would rate both Edison and John Ericsson above him. Ericsson, in particular, had much more long-term influence on the evolution of both commercial and military ships than did Brunel. Our resident blind squirrel, Mr. Wright, has found a rare nut by noting Brunel’s signal violations of Musk’s “the best part is no part” design principle anent the Great Eastern.

wayne,

There was – and still is – a Carnegie Library in my hometown, which was founded as an iron ore transshipment port during the Civil War. Carnegie prioritized towns and cities with connections to the steel industry for his bibliothecaen largesse. The town had a local lumber baron or two, but Carnegie ninja-ed them all anent the library.

I wish he had done the same with the timber barons here…they own the state.

Robert wrote: “In the 2000s Musk has not had as free a hand as Vanderbilt. Our modern administrative state controls too much of American business.”

Ah, the Victorian Age, when the whole world changed. What a time that was, with the freedom to innovate and invent, with very little government interference, which is why we got so many creative inventions. Power was a major driver, from the implementation of steam, invented only a century before, to electricity, discovered about a century earlier, to tunneling, to steel structures, to … what the heck, let’s include powered and controlled manned flight in that era.

The railroad was the invention that allowed goods and people to travel across all lands for very little cost, both in time and money, spreading civilization across continents faster than sailing ships spread it around the world. In the late 19th century, people expected everything would soon run on electricity, and so it has, except for ships, airplanes, and rockets — with light airplanes now beginning to be electrified, and some spacecraft thrusters being electrically powered, too.

So, I vote for the railroad man as the Victorian Age Elon Musk, edging out our heavy reliance upon NikolaTesla’s research and inventions, which are the basis for so much of our electrical systems.

“For Tesla he relied on government subsidies.”

It was less a reliance as it was an imposition. Congress wanted electric vehicles (EVs), but the auto industry was reluctant to produce what was not desired by their customers. Musk, on the other hand, made sure that Tesla’s EVs were desirable. The “subsidies,” which were really only tax credits for the buyers, only covered a limited number of EVs from the manufacturers, so Tesla did not receive as much money per car, on average, as virtually everyone assumes. The tax credits did not make Tesla’s competitors’ EVs much more desirable, which is something else virtually no one takes into consideration.

__________

Jeff Wright wrote: “ People had no fear of size then… something space launch had an issue with until recently. ”

Space launch did not have much need for large launch vehicles until recently, and even now it is mostly for getting to Mars, just as the previous super heavy launch vehicle, the Saturn V, had the purpose of getting to the Moon.

“For the longest time in the USA, our philosophy was to miniaturize the payload.”

It still is. This is why smallsats are making such a rapid comeback.

But the statement is not entirely correct. From the 1980s (or earlier) the philosophy was to maximize the number of payloads, or instruments, on a satellite, because the cost of launch was so high and the launch cadence so low that it was better to have large satellites with a multitude of payload capacity or capability. The instruments themselves were generally made smaller and miniaturized. It wasn’t until the 1990s that NASA decided to change its Mars mission philosophy to “Faster, better, cheaper,” which required smaller satellites to do the faster and cheaper parts. This philosophy didn’t work out as well as expected.

“To this day, there are folks even in NewSpace that still balk at the SHLLV concept.”

To this day, there is no demand for a super heavy lift-launch vehicle. Without demand, nobody wants to invest in one.

Even Starship has yet to inspire many ideas for large-sized payloads that fit only inside its body, and it has not yet inspired ideas for heavy payloads that require such a capable launch vehicle. Starlab is counting on Starship to launch its space station module(s), but off the top of my head I cannot think of anyone else.

“Trucks, ships and planes have increased in size–but for the longest time, rockets stayed in the Delta family payload range.”

There is a maximum reasonable size for everything. We seem to have reached that size for ocean ships, aircraft, and ground vehicles traveling on U.S. roadways. It is possible that Starship is approaching maximum size for an Earth-launched space vehicle.

Elon’s fundamental drive since the sale of PayPal has been to ensure the long-term survival of technologic civilization so that it would continue to discover the question to which the universe is the answer. He has explicitly stated this time and again.

He started SpaceX not for the money — he anticipated losing that investment. He started Tesla not for money — he points out that no new car company had survived for the last century. Rather, making money was the necessary means to achieving the above-stated goal. Even about Starship, he stated that, even if they failed, he hoped that they would advance the technology as far as they could.

He chose not to dedicate a lot of his time on ventures he felt good but not essential to the survival of the human species — Hyperloop, Boring Company, electric jets, & X.com banking.

His entry into politics (Twitter, Trump, DOGE) was only to ensure that technologic civilization would not be stagnated by uni-party rule & suffocating regulation. I discussed all of this on a recent Space Show appearance.

Hello Dick!

“I don’t think Brunel was the greatest engineer of the 19th century. I would rate both Edison and John Ericsson above him. Ericsson, in particular, had much more long-term influence on the evolution of both commercial and military ships than did Brunel.”

See, I think there’s a way to see both of our statements as true and not contradictory. Ericsson pretty arguably *did* have a much bigger influence on the evolution of maritime technology ( mainly in naval design) than Brunel did; but a big reason was longevity, along with focus. Brunel died at just 53, of a stroke; Ericsson made it deep into his 80s and his big breakthroughs came late in life. (A similar observation about Edison springs to mind here, too, I might say.) Brunel also ended up devoting a lot of his career to infrastructure on land (bridges, tunnels, etc.) whereas Ericsson was a more purely naval being.

“Greatest” is, just the same, one of those terms with a lot of subjectivity. I’m not sure there’s a way to ever resolve a debate like this. Each was a genius in his own way; in breadth and scale of achievement, Elon Musk has blown past both, though he does stand tall on their broad shoulders, among others. We are very lucky to have him.