Billionaire to fund construction of an orbiting optical telescope larger than Hubble

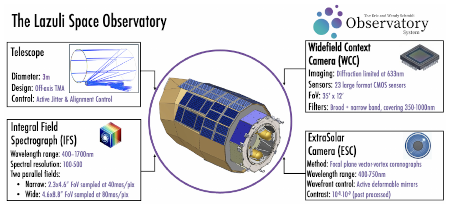

Figure 1 from the proposal paper [pdf].

Schmidt Sciences, a foundation created by one of Google’s founders, announced yesterday it is financing the construction of four new research telescopes, one of which will be an orbiting optical telescope with a mirror 3.1 meters in diameter, larger than the 2.4 meter primary mirror on the Hubble Space Telescope.

Today at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society, Schmidt Sciences, a foundation backed by billionaires Eric and Wendy Schmidt, announced one of the largest ever private investments in astronomy: funding for an orbiting observatory larger than NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, along with funds to build three novel ground-based observatories. The project aims to have all four components up and running by the end of the decade.

“We’re providing a new set of windows into the universe,” says Stuart Feldman, president of Schmidt Sciences, which will manage the observatory system. Time on the telescopes will be open to scientists worldwide, and data harvested by them will be available in linked databases. Schmidt Sciences declined to say how much it is investing but Feldman says the space telescope, called Lazuli, alone will cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Eric Schmidt was once CEO of Google, and in recent years has been spending his large fortune (estimated to exceed $50 billion) on space ventures. For example, in March 2025 he acquired control of the rocket startup Relativity.

While the three new ground-based telescopes will do important work, the Lazuli space telescope is by far the most important, not only scientifically but culturally. Prior to World War II, all big telescopes were built in this way, using private funds usually donated by wealthy philanthropists, a system controlled by the private sector that encouraged the efficient and fast construction. At the same time, it did not limit the possibilities. For the first half of the 20th century the United States built all of the world’s biggest telescopes, setting new records in size with each.

Post World War II however the government took over such funding, and while this government system has produced some great science, including all the great space telescopes of the past six decades, it has also limited options in many ways. For example, though optical astronomers have been proposing Hubble replacements now for almost three decades, they have not had the political clout to get funding. NASA has instead focused on other areas, such as deep space infrared cosmology using the Webb Space Telescope.

Schmidt’s decision to fund a new optical telescope larger than Hubble brings us back to the older capitalist model. Under this model we are likely to get a much larger variety of new projects, because we won’t be limited to one entity, NASA, to get them funded. Any rich person who wants to put their name on a new project can make something happen, as Eric and Wendy Schmidt are now doing.

You can find out the specifics of the Lazuli telescope here [pdf]. It will have three instruments, an optical camera, an infrared spectrograph, and a coronagraph that will block the bright light of stars so that dimmer companiion objects can be photographed. From the abstract:

Operating from a 3:1 lunar-resonant orbit, Lazuli will respond to targets of

opportunity in under four hours—a programmatic requirement designed to enable routine temporal

responsiveness that is unprecedented for a space telescope of this size. Lazuli’s technical capabilities

are shaped around three broad science areas: (1) time-domain and multi-messenger astronomy, (2)

stars and planets, and (3) cosmology. These capabilities enable a potent mix of science spanning

gravitational wave counterpart characterization, fast-evolving transients, Type Ia supernova cosmol-

ogy, high-contrast exoplanet imaging, and spectroscopy of exoplanet atmospheres. While these areas

guide the observatory design, Lazuli is conceived as a general-purpose facility capable of supporting

a wide range of astrophysical investigations, with open time for the global community. We describe

the observatory architecture and capabilities in the preliminary design phase, with science operations

anticipated following a rapid development cycle from concept to launch.

Though the paper does not outline a specific launch schedule, it appears the goal is to have this telescope in orbit before the end of this decade.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

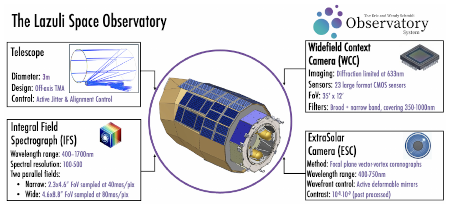

Figure 1 from the proposal paper [pdf].

Schmidt Sciences, a foundation created by one of Google’s founders, announced yesterday it is financing the construction of four new research telescopes, one of which will be an orbiting optical telescope with a mirror 3.1 meters in diameter, larger than the 2.4 meter primary mirror on the Hubble Space Telescope.

Today at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society, Schmidt Sciences, a foundation backed by billionaires Eric and Wendy Schmidt, announced one of the largest ever private investments in astronomy: funding for an orbiting observatory larger than NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, along with funds to build three novel ground-based observatories. The project aims to have all four components up and running by the end of the decade.

“We’re providing a new set of windows into the universe,” says Stuart Feldman, president of Schmidt Sciences, which will manage the observatory system. Time on the telescopes will be open to scientists worldwide, and data harvested by them will be available in linked databases. Schmidt Sciences declined to say how much it is investing but Feldman says the space telescope, called Lazuli, alone will cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Eric Schmidt was once CEO of Google, and in recent years has been spending his large fortune (estimated to exceed $50 billion) on space ventures. For example, in March 2025 he acquired control of the rocket startup Relativity.

While the three new ground-based telescopes will do important work, the Lazuli space telescope is by far the most important, not only scientifically but culturally. Prior to World War II, all big telescopes were built in this way, using private funds usually donated by wealthy philanthropists, a system controlled by the private sector that encouraged the efficient and fast construction. At the same time, it did not limit the possibilities. For the first half of the 20th century the United States built all of the world’s biggest telescopes, setting new records in size with each.

Post World War II however the government took over such funding, and while this government system has produced some great science, including all the great space telescopes of the past six decades, it has also limited options in many ways. For example, though optical astronomers have been proposing Hubble replacements now for almost three decades, they have not had the political clout to get funding. NASA has instead focused on other areas, such as deep space infrared cosmology using the Webb Space Telescope.

Schmidt’s decision to fund a new optical telescope larger than Hubble brings us back to the older capitalist model. Under this model we are likely to get a much larger variety of new projects, because we won’t be limited to one entity, NASA, to get them funded. Any rich person who wants to put their name on a new project can make something happen, as Eric and Wendy Schmidt are now doing.

You can find out the specifics of the Lazuli telescope here [pdf]. It will have three instruments, an optical camera, an infrared spectrograph, and a coronagraph that will block the bright light of stars so that dimmer companiion objects can be photographed. From the abstract:

Operating from a 3:1 lunar-resonant orbit, Lazuli will respond to targets of

opportunity in under four hours—a programmatic requirement designed to enable routine temporal

responsiveness that is unprecedented for a space telescope of this size. Lazuli’s technical capabilities

are shaped around three broad science areas: (1) time-domain and multi-messenger astronomy, (2)

stars and planets, and (3) cosmology. These capabilities enable a potent mix of science spanning

gravitational wave counterpart characterization, fast-evolving transients, Type Ia supernova cosmol-

ogy, high-contrast exoplanet imaging, and spectroscopy of exoplanet atmospheres. While these areas

guide the observatory design, Lazuli is conceived as a general-purpose facility capable of supporting

a wide range of astrophysical investigations, with open time for the global community. We describe

the observatory architecture and capabilities in the preliminary design phase, with science operations

anticipated following a rapid development cycle from concept to launch.

Though the paper does not outline a specific launch schedule, it appears the goal is to have this telescope in orbit before the end of this decade.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

This is the way!

Great development!

(Firm believer that an optical picture is worth a billion dollars.)

“The Hubble Space Telescope and The Visionaries Who Built It”

Explorer’s Club (June 2008)

(1:24:20)

https://archive.org/details/the-hubble-space-telescope-and-the-visionaries-who-built-it

Didn’t Issackmann want to fund a repair and update of Hubble? But NASA turned it down with vengeance..

Yes, Isaacman proposed reboosting Hubble at no cost to NASA. They shot it down, and their reasons come off mainly as not-invented-here.

I hope Lazuli is only the first in a long series of privately-funded scientific programs; they are gradually increasing in number (Rocket Lab has their Venus mission, Blue Skies presently has their Mauve ultraviolet scope in orbit), and they’re likely to be both more affordable and ultimately more effective than government-driven science, which far too often is bent towards serving the whims of power.

Lazuli will have a larger mirror than Hubble and is NET 2028. As Schmidt is CEO of Relativity, I wonder if he’ll push for the company to launch the telescope, or if it’ll be bid out to whomever offers the best deal.

Schmidt is not exactly one of my favorite guys going all the way back to his pre-billionaire days at Novell, but this is definitely a good move.

The comments on Berger’s story about this over at Ars Technica were, quite predictably, much less about astronomy than about various schemes for depriving the wealthy of their wealth – all in the “public interest” of course.

Hello Dick,

1. I mean, yeah, it’s Ars Technica, and more and more of the regular commenters even on Berger’s and Clark’s stories are bitter PMC BreadTube sorts who live on resentment. But there’s much worse out there; just check the Reddit threads on this story….

I do think this project represents a transitional development; it’s still dependent on the magnanimity of an ultra-rich patron, and without that there really isn’t a business case per se that could close for these telescopes. Not that there isn’t precedent for that kind of thing in the great pre-WW2 tradition of privately funded research; quite a lot of polar exploration was funded this way, and the payoff to the wealthy sponsors was most often naming legacies, i.e., “Find a big geographical feature you can name after me, old boy.” (The Boothia Peninsula and the Beardmore Glacier are prime examples.) But this *could* lead us to a point in the not-too-distant future where not only the cost and ease of launch but also the fabrication of space telescopes could come down to a point where someone *could* close a business case on deploying ’em.

2. Launch and lifespan particularly interested me, so I made a priority of looking into that. At 4,000kg, even a Falcon 9 could get this to a lunar resonant orbit, from what I can make out; obviously it could also launch on a Falcon Heavy, a New Glenn 7×2 or (of course) a Starship. If they can really achieve their 3-5 year development and fabrication cycle, then deployment by 2030 seems achievable, too. They are still mum on mission lifespan, even though the term is referenced repeatedly in the study paper; what *is* clear is that the orbit they have identified will not a limiting factor: “The orbit is long-term stable, requiring minimal station-keeping maneuvers, maintaining perigee above the geosynchronous belt for at least 100 years, and requiring no end-of-life disposal maneuvers.”

I missed this question: “As Schmidt is CEO of Relativity, I wonder if he’ll push for the company to launch the telescope, or if it’ll be bid out to whomever offers the best deal.”

We do not know what Terran R’s payload mass to lunar orbits is, though I tend to assume that given its LEO capability and the power of its upper stage, a 4,000kg payload is likely workable. Schmidt may well want it on a Terran R if possible. What I really wonder is whether Terran R will actually be operational by the time this telescope is ready. It seems like the most doubtful of the major medium/heavy lift rockets in development in America right now. Even if it makes it off a launch pad, I seriously wonder if it can survive in the launch market of the late 2020’s.

P.S. I clean forgot about Vulcan; even its lower end versions could get this to lunar orbit, too. But it will likely be more expensive than the other options, and even by 2028-30 it will likely still be working through its NSSL and Amazon backlogs….

The point is, though, access and cost of launch are simply not going to be a problem for Lazuli. That’s the great new world of launch we have now arriving, thanks to Elon Musk.

Man, if I had a billion dollars, I’d have my own space telescope too.

One tidbit I can’t find is how are they going to award observing time, and what’s the fee schedule; and how does that compare to government space scopes?

Richard M., you are correct on precedent of patrons funding research and telescopes. I remember Andrew Carnegie funded Mt.Wilson observatory, Griffith Observatory was funded by Griffith J. Griffith, and the Rockefeller Foundation with Palomar, etc…

John.,

“One tidbit I can’t find is how are they going to award observing time, and what’s the fee schedule; and how does that compare to government space scopes?”

Here is what Eric Berger wrote about that in his Ars Technica article:

Beyond that, however, we do not have any details yet about how that competition will work, or exactly who will be running it.

This is 3 meters.

Did he not want to use the other NRO mirror?

https://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/space-exploration/deep-space/nasa-hold-workshop-determine-donated-nro-telescopes/

He could have had a WFIRST clone.

Light buckets are better the wider they are.

Richard M: I sometimes wonder that too, but Schmidt seems determined to turn the company around. Whether he’ll end up like Bezos and fund it with his own fortune, I can’t say, but he is interested in orbital data centers too, which if they pan out could supply the demand Relativity needs.

Hello Jay,

“Richard M., you are correct on precedent of patrons funding research and telescopes. I remember Andrew Carnegie funded Mt.Wilson observatory, Griffith Observatory was funded by Griffith J. Griffith, and the Rockefeller Foundation with Palomar, etc…”

The list of privately funded telescopes is a long one! The 18th and 19th centuries featured loads of these, mainly in the British Empire and America: A.A. Common, Thomas Grubb, William Lassell, James Short, John D. Hooker, etc.

It looks like we may be entering another such age of privately funded major astronomy, no matter how much it appalls online progressives who wish such things to be exclusively in the purview of technocrats with invincible public sinecures who think just like they do.

Hello Jeff,

“Did he not want to use the other NRO mirror?”

The problem is twofold: a) The NRO would insist that its mirror be employed only in a telescope under the control of the government, for national security reasons, and b) actually working such a mirror into a space telescope is a ton of work and expense, to the point that some have questioned whether it was much of an advantage to NASA to use it in the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope . . . and anyway, the mirror was only a small part of Roman’s total expense, so it likely did not save NASA much money. Going “clean sheet” clearly seems to be a faster route anyway, even if the NRO *did* sign off on donating its mirror. Schmidt and his colleagues clearly want to get this thing into space as fast as possible. Quote: “The president of the philanthropic organization, Stuart Feldman, said he was not ready to disclose the telescope’s primary contractors yet. But he said a key goal of this telescope, and the other three projects, is to move quickly. Moving from a telescope concept to launching hardware in less than five years would be rapid indeed.”

Hello Nate,

“Richard M: I sometimes wonder that too, but Schmidt seems determined to turn the company around. Whether he’ll end up like Bezos and fund it with his own fortune, I can’t say, but he is interested in orbital data centers too, which if they pan out could supply the demand Relativity needs.”

I think . . . if there’s any sort of consensus in the industry about how many medium/heavy launchers the U.S./Western payload market can support over the next ten years, it’s probably about three of ’em. That market will lean heavily on NSSL payloads and LEO constellations. For the next three years (2026-28), those three providers will be SpaceX, ULA, and Blue Origin. After that, ULA’s steady fade will unfold, and Rocket Lab, Firefly/Northrop, Stoke, and Relativity will vie for whatever Musk and Bezos can’t nail down. (Ariane 6, GSLV and H3 will be active players, too, but with special and quite limited market niches that won’t really impact this question.)

But thinking has yet to crystallize about how AI data center networks in orbit might change this equation. I do not think anyone can answer that yet. But it is quite possible that it could open up viable slots for more launch providers. Still, I have to think Relativity ranks at the bottom of the list, so I think there’s going to need to be a whole lot of AI business for Relativity to make it, no matter how much Schmidt opens up his checkbook.

It is noteworthy that Eric Berger made a comment in the combox of his Ars Technica article about what this telescope would launch on. He asked directly about that, and the response was that Falcon 9’s payload fairing would accommodate Lazuli. So, right now at least, Schmidt and his colleagues seem to be thinking about launching this thing on a Falcon. Maybe that will change as other rockets reach the market. Stay tuned.

Richard M: Based on the paper describing in detail the telescope and the plans (which I linked to and people should read before commenting) doling out observing time will likely following a system comparable to that used for Hubble and Webb. It is what the astronomy community is used to, and knows how to do.

Congratulations Bob. This is the type of thing, on the predictable side, that capitalism in space brings us. :)

Hello Bob,

I admit that I skimmed a lot of the paper — it is a long read! — but in regards to this question, the one passage that struck me as relevant on this point was this one on page 25:

In broad strokes, this does seem to resemble how Hubble time is parceled out, and clearly they had Hubble (and other telescopes NASA runs) in mind. But since there are no fees, nor NASA regulations to bind them, and because they don’t spell out how this will work in any more detail here, I was just hesitant to go too far in assuming how closely they will follow NASA precedent.

If there’s something else I missed….well, I am happy to get to it.

Richard M: The use of a Time Allocation Committee is EXACTLY how things are done with Hubble, Webb, and most NASA telescopes. The astronomy community assembles a committee to review proposals and arrange time. It is however also carefully watched and supervised by other astronomy organizations to make sure it is fair.

NASA’s only real rules involve two limitations. One, data must be made fully public one year after observations (though even this is relaxed as the telescope ages). Two, if other nations or space agency contributed to the building of the telescope their astronomers get a guaranteed percentage of the observing time.

In the case of Hubble, that was 15% forever, even though Europe’s contribution involved an instrument that produced little science and was replaced by an early repair mission, and solar panels that were badly designed, caused the telescope to vibrate (ruining all images), and were replaced on the FIRST repair mission.

This private telescope will likely have its own rules, but based on the paper I suspect it will actually dole out time more fairly.

Richard M: By the way, I didn’t mean to sound like I was criticizing you in my earlier comment. I do find that too many readers throw out questions that just a few seconds of research, using the sources I ALWAYS link to, could have been answered. I provide those sources expressly to give people a chance to learn.

I didn’t intend to apply that to you.

Hello Bob,

Thank you for the replies. I *was* starting to fear that I was in danger of becoming an irritant to you with my barrage of comments, which I would hate to be the case, because you have done a great job of coverage and commentary on what has shaped up to be one of the most important news days we have had about space in quite a while!

I don’t have anything more to add to what you have just said about the TAC process and how the Lazuli team might end up employing it. We all look forward eagerly to see how it unfolds.

I would like to risk adding one more contribution to the discussion, if I may. This is a comment made just now by VSECOTSPE (whose real identity I do not wish to reveal, even if it is not too hard to figure out) over in the NSF forums, and I do so because he is a credible observer who knows some of the principals involved, and he is not a hack or an anti-commercial chap, and his sober tonic is worth considering:

I think his most pertinent paragraph is his second one: We can’t judge schedule because we don’t know enough. I *suspect* that a 2028 launch is probably too optimistic unless they’ve done more work than we think (and maybe they have! We just don’t know.). I also *suspect* that 2035 seems excessively pessimistic. It is . . . hard to say. NASA had great expertise and experience in developing Roman and it also had a number of institutional constraints in how it had to do it. Schmidt really is the first out of the box on doing something like this, and our previous history of space telescope development, let alone pre-WW2 ground telescopes, may be difficult to apply at every point to what he is attempting. And how this plays out will do a lot to establish a template for how other, future privately funded major space telescopes will be built and operated. And if it takes a few more years to get deployed than he hopes and promises today, well, it’s still a massively useful step forward.

We live in a promising moment for space.

This is good news and about time. Technologies and capabilities are so far advanced over Hubble that this billionaire will get a lot of bang for his buck.

Unlike NASA programs which builds an “overpriced one of a kind”… this new telescope could be built with expandability in mind using the tools that created it, to produce more with the same castings…

Create a dozen more getting cheaper each time. This lets more work to be performed on a dozen separate projects? Or lash a group of them together to look at the same object with unbelievable resolution.

As Jeff Wright said;

Light buckets are better the wider they are.

Richard M,

I think it must be close to a decade since I last paid a visit to reddit about anything space-related. That was before it descended to the woke depths it currently occupies. Back then, the wackos there weren’t political, they were Moon Landing Deniers, Flat Earthers, Geocentrists, Firmamentarians and such-like. Screwballs, but not evil. Better times.

This Lazuli project will break trail for what I expect to be a great many other purely private-sector basic space science initiatives of many different types and sizes that will follow in coming years. NASA and the rest of the significant national space agencies will find that they must fit their own future space science efforts into whatever gaps remain as there will be no support for “me-too” efforts anent what the private sector has taken on. I think Jared Isaacman assumes the NASA Administrator chair just in time to demonstrate that he’s exactly the guy to work those gaps.

This is the answer to the question I had, which is:

How are the missions coordinated with what scientists need? Normally we do that with Decadals.

The answer is in the PDF:

“….our priorities are well aligned with the recommendations of the Astro2020

Decadal Survey (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021) and complement existing

and planned observatories by performing precursor observations allowing target and technique optimizations

for future missions, technology maturation, and follow-up of high value targets”

This gives the whole project a good chance of success.

If billionaires can start rocket companies they certainly can fund telescopes.

I wish this project the very best of luck. Those that think the ONLY way to execute space science is via the government must need a wardrobe change.

Richard M: Some considerations as to Lazuli’s proposed 2028 launch date:

1. As astronomers have been proposing variations of Lazuli for decades, to no avail, a lot of the design work already exists.

2. Not being a NASA project, I am certain they are foregoing a lot of the make work that goes with every NASA project. For example, with every new telescope new software is written, even if perfectly good software already exists. I was told this by the guy initially hired to write this software for Roman, and have seen it myself time after time.

3. That 2028 date is without doubt an “Elon Musk” schedule. It is aggressive to push things, but understood it will likely not be met.

Never heard of a 3:1 lunar-resonant orbit before. Learn something every day!

Hello Bob,

“That 2028 date is without doubt an “Elon Musk” schedule. It is aggressive to push things, but understood it will likely not be met.”

I suspect you’re correct!

I wonder if they cold make a multi mirror telescope to get a larger size than Hubble?

A 2 meter mirror would be cheaper and more stable than a 3 meter mirror.

Plus 6 2meter hexagon mirrors would end up forming a 6 meter mirror.

To Richard M

I like the idea of in-space server farms in that it helps space companies and paves the way for powersats in some respects…but computing advances come so quickly that plans can be spoiled:

https://phys.org/news/2026-01-radio-enable-energy-efficient-ai.html

Now, might that actually *aid* powersat/serversat two-for-ones? Or interfere?