Reanalysis of Webb data discovers more than a hundred very small main-belt asteroids

Using data from the Webb Space Telescope in an unexpected way, astronomers have discovered 138 asteroids in the main asteroid belt, most of which are the smallest so far detected.

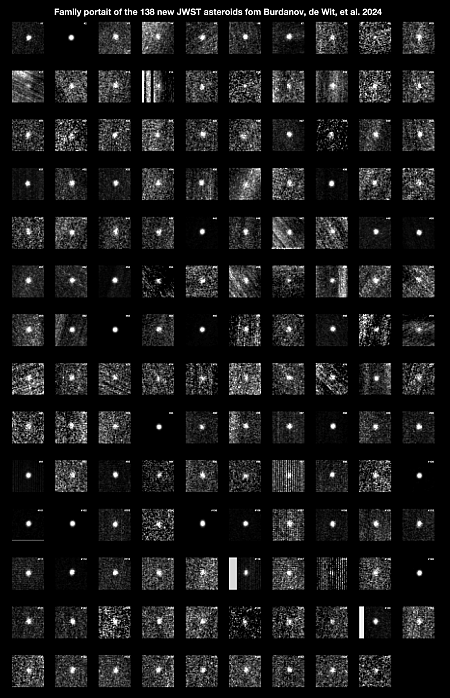

The picture to the right shows all 138 asteroids. The researchers had originally used Webb to study the atmospheres of the exoplanets that orbit the star TRAPPIST-1. They then thought, why not see if their data also showed the existence of asteroids in our own solar system. By blinking between multiple images they might spot the movement of solar system objects moving across the field of view. From the press release:

The team applied this approach to more than 10 000 [Webb] images of the TRAPPIST-1 field, which were originally obtained to search for signs of atmospheres around the system’s inner planets. By chance TRAPPIST-1 is located right on the ecliptic, the plane of the solar system where all planets and most asteroids lie and orbit around the Sun. After processing the images, the researchers were able to spot eight known asteroids in the main belt. They then looked further and discovered 138 new asteroids, all within tens of meters in diameter — the smallest main belt asteroids detected to date. They suspect a few asteroids are on their way to becoming near-Earth objects, while one is likely a Trojan — an asteroid that trails Jupiter.

The data is insufficient for most of these objects to chart their orbits precisely. Based on this one single study, however, it suggests that pointing Webb along the ecliptic in almost any direction will detect more such objects. Do this enough and astronomers might actually be able to get a rough census of the asteroid belt’s population.

Using data from the Webb Space Telescope in an unexpected way, astronomers have discovered 138 asteroids in the main asteroid belt, most of which are the smallest so far detected.

The picture to the right shows all 138 asteroids. The researchers had originally used Webb to study the atmospheres of the exoplanets that orbit the star TRAPPIST-1. They then thought, why not see if their data also showed the existence of asteroids in our own solar system. By blinking between multiple images they might spot the movement of solar system objects moving across the field of view. From the press release:

The team applied this approach to more than 10 000 [Webb] images of the TRAPPIST-1 field, which were originally obtained to search for signs of atmospheres around the system’s inner planets. By chance TRAPPIST-1 is located right on the ecliptic, the plane of the solar system where all planets and most asteroids lie and orbit around the Sun. After processing the images, the researchers were able to spot eight known asteroids in the main belt. They then looked further and discovered 138 new asteroids, all within tens of meters in diameter — the smallest main belt asteroids detected to date. They suspect a few asteroids are on their way to becoming near-Earth objects, while one is likely a Trojan — an asteroid that trails Jupiter.

The data is insufficient for most of these objects to chart their orbits precisely. Based on this one single study, however, it suggests that pointing Webb along the ecliptic in almost any direction will detect more such objects. Do this enough and astronomers might actually be able to get a rough census of the asteroid belt’s population.