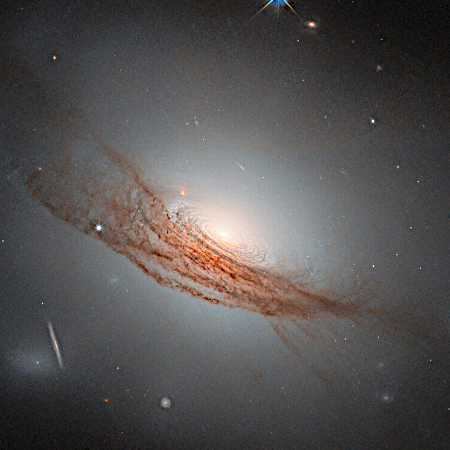

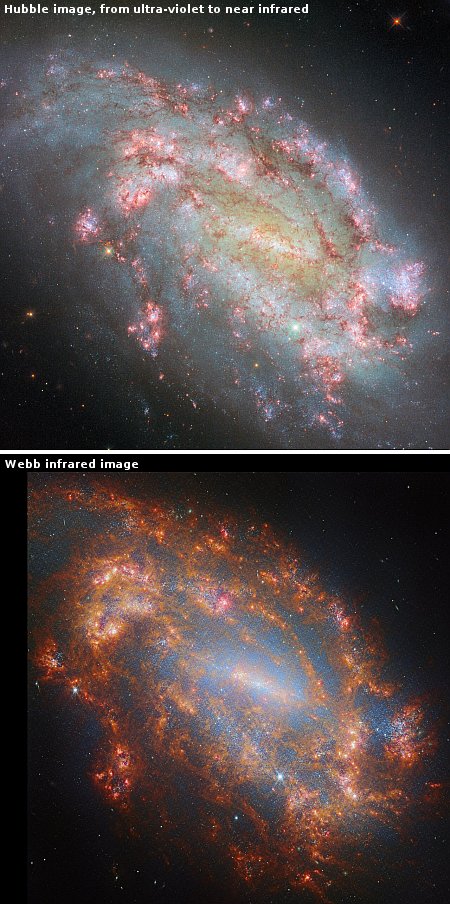

A galaxy’s swirling dust lanes

Cool image time! The picture to the right, cropped, reduced, and enhanced to post here, was taken by the Hubble Space Telescope as part of follow-up observations of a now faded supernovae that occurred there two years earlier.

This was on purpose: the aim of the observations was to witness the aftereffects of the supernova and examine its surroundings, which can only be done once the intense light of the explosion is gone.

The galaxy itself, NGC 7722, is 187 million light years away, and is unusual in itself.

A “lenticular”, meaning “lens-shaped”, galaxy is a type that sits in between the more familiar spiral galaxies and elliptical galaxies. It is also less common than these — partly because when a galaxy has an ambiguous appearance, it can be hard to determine if it is actually a spiral, actually an elliptical galaxy, or something in between. Many of the known lenticular galaxies sport features of both spiral and elliptical galaxies. In this case, NGC 7722 lacks the defined arms of a spiral galaxy, while it has an extended, glowing halo and a bright bulge in the center similar to an elliptical galaxy. Unlike elliptical galaxies, it has a visible disc — concentric rings swirl around its bright nucleus. Its most prominent feature, however, is undoubtedly the long lanes of dark red dust coiling around the outer disc and halo.

The streak in the lower left is a very distant background galaxy, seen on edge.

Cool image time! The picture to the right, cropped, reduced, and enhanced to post here, was taken by the Hubble Space Telescope as part of follow-up observations of a now faded supernovae that occurred there two years earlier.

This was on purpose: the aim of the observations was to witness the aftereffects of the supernova and examine its surroundings, which can only be done once the intense light of the explosion is gone.

The galaxy itself, NGC 7722, is 187 million light years away, and is unusual in itself.

A “lenticular”, meaning “lens-shaped”, galaxy is a type that sits in between the more familiar spiral galaxies and elliptical galaxies. It is also less common than these — partly because when a galaxy has an ambiguous appearance, it can be hard to determine if it is actually a spiral, actually an elliptical galaxy, or something in between. Many of the known lenticular galaxies sport features of both spiral and elliptical galaxies. In this case, NGC 7722 lacks the defined arms of a spiral galaxy, while it has an extended, glowing halo and a bright bulge in the center similar to an elliptical galaxy. Unlike elliptical galaxies, it has a visible disc — concentric rings swirl around its bright nucleus. Its most prominent feature, however, is undoubtedly the long lanes of dark red dust coiling around the outer disc and halo.

The streak in the lower left is a very distant background galaxy, seen on edge.