Old and new optical space telescopes team up to view the Cat’s Eye

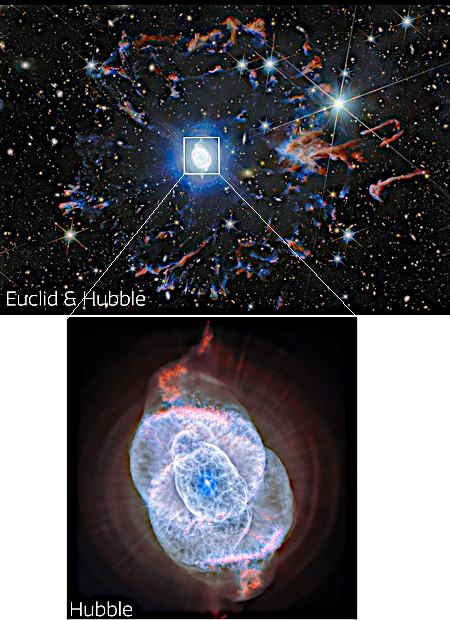

Astronomers using both NASA’s long established Hubble Space Telescope and Europe’s new Euclid space telescope have produced new optical/infrared images of the Cat’s Eye planetary nebula.

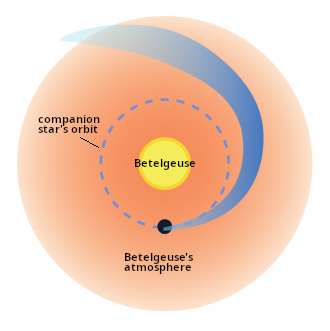

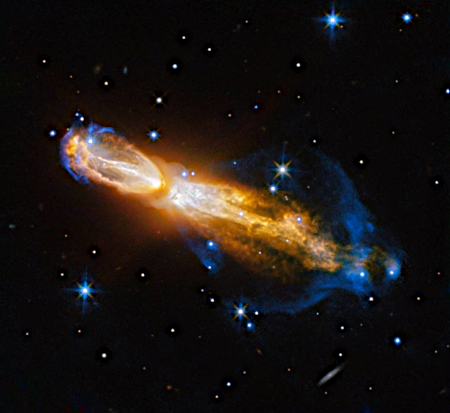

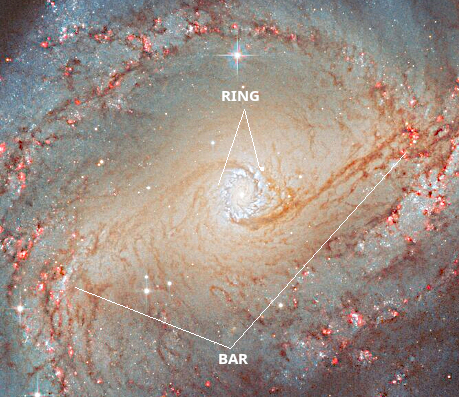

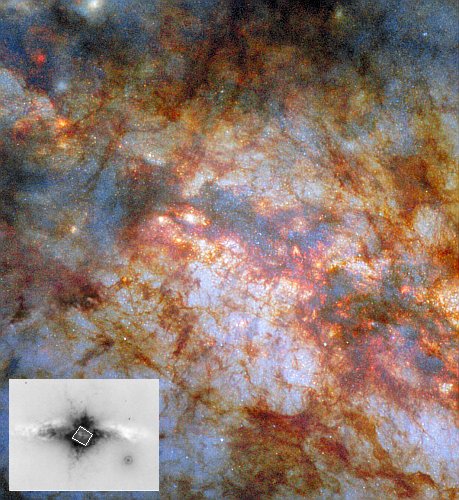

Those images are to the right, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here. The Hubble image at bottom shows the complex structure of the nebula itself, located about 4,400 light years away and believed created by the inner orbital motions of a binary star system that act almost like the blades in a blender, mixing the material thrown off by one or both of the stars as they erupt in their latter stages of life.

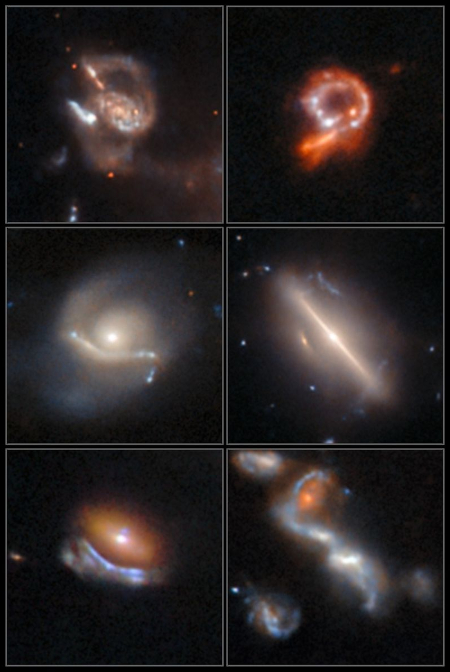

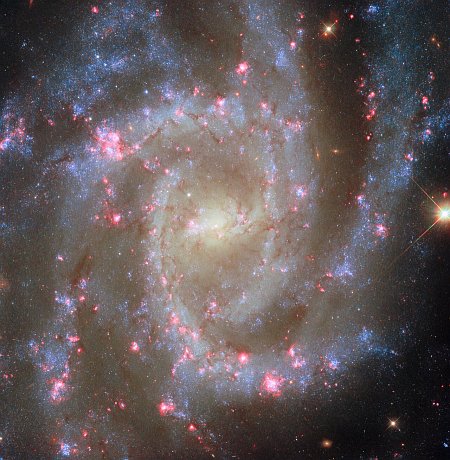

In Euclid’s wide, near-infrared, and visible light view, the arcs and filaments of the nebula’s bright central region are situated within a halo of colorful fragments of gas zooming away from the star. This ring was ejected from the star at an earlier stage, before the main nebula at the center formed. The whole nebula stands out against a backdrop teeming with distant galaxies, demonstrating how local astrophysical beauty and the farthest reaches of the cosmos can be seen together with Euclid.

Euclid has a primary mirror 1.2 meters in diameter, about half that of Hubble. Though it can’t zoom in with the same resolution, its view is as sharp since it is in space above the atmosphere. It thus provides a wider view, which in this case helps provide a larger context to the detailed close-up view provided by Hubble.

In many ways Euclid is Hubble’s replacement, produced by the European Space Agency, as NASA and the American astronomy community has not been able to get together to build their own new optical orbiting telescope.

Astronomers using both NASA’s long established Hubble Space Telescope and Europe’s new Euclid space telescope have produced new optical/infrared images of the Cat’s Eye planetary nebula.

Those images are to the right, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here. The Hubble image at bottom shows the complex structure of the nebula itself, located about 4,400 light years away and believed created by the inner orbital motions of a binary star system that act almost like the blades in a blender, mixing the material thrown off by one or both of the stars as they erupt in their latter stages of life.

In Euclid’s wide, near-infrared, and visible light view, the arcs and filaments of the nebula’s bright central region are situated within a halo of colorful fragments of gas zooming away from the star. This ring was ejected from the star at an earlier stage, before the main nebula at the center formed. The whole nebula stands out against a backdrop teeming with distant galaxies, demonstrating how local astrophysical beauty and the farthest reaches of the cosmos can be seen together with Euclid.

Euclid has a primary mirror 1.2 meters in diameter, about half that of Hubble. Though it can’t zoom in with the same resolution, its view is as sharp since it is in space above the atmosphere. It thus provides a wider view, which in this case helps provide a larger context to the detailed close-up view provided by Hubble.

In many ways Euclid is Hubble’s replacement, produced by the European Space Agency, as NASA and the American astronomy community has not been able to get together to build their own new optical orbiting telescope.