New data from VLT uncovers numerous debris disks around stars

Using a new instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, astronomers have compiled a catalog of 51 potential exoplanet solar systems, all with intriguing debris disks surround the stars with features suggesting the existence of asteroids and comets.

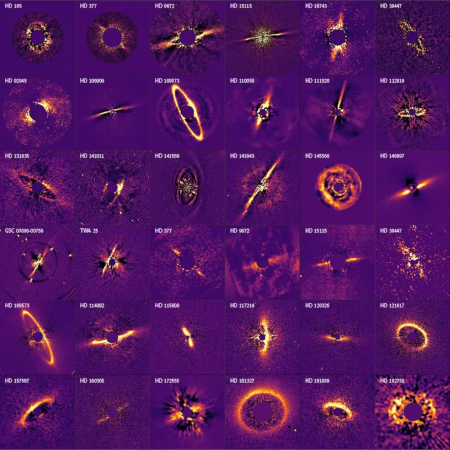

The image to the right shows a sampling of those systems. From the press release:

“To obtain this collection, we processed data from observations of 161 nearby young stars whose infrared emission strongly indicates the presence of a debris disk,” says Natalia Engler (ETH Zurich), the lead author of the study. “The resulting images show 51 debris disks with a variety of properties — some smaller, some larger, some seen from the side and some nearly face-on – and a considerable diversity of disk structures. Four of the disks had never been imaged before.”

Comparisons within a larger sample are crucial for discovering the systematics behind object properties. In this case, an analysis of the 51 debris disks and their stars confirmed several systematic trends: When a young star is more massive, its debris disk tends to have more mass as well. The same is true for debris disks where the majority of the material is located at a greater distance from the central star.

Arguably the most interesting feature of the SPHERE debris disks are the structures within the disks themselves. In many of the images, disks have a concentric ring- or band-like structure, with disk material predominantly found at specific distances from the central star. The distribution of small bodies in our own solar system has a similar structure, with small bodies concentrated in the asteroid belt (asteroids) and the Kuiper belt (comets).

The data from various telescopes both on the ground and in space is increasingly telling us that our solar system is not unique, and that the galaxy is filled with millions of similar systems, all in different states of formation. This hypothesis is further strengthened by the appearance of interstellar comet 3I/Atlas, which despite coming from outside our solar system is remarkably similar to the comets formed here.

Using a new instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, astronomers have compiled a catalog of 51 potential exoplanet solar systems, all with intriguing debris disks surround the stars with features suggesting the existence of asteroids and comets.

The image to the right shows a sampling of those systems. From the press release:

“To obtain this collection, we processed data from observations of 161 nearby young stars whose infrared emission strongly indicates the presence of a debris disk,” says Natalia Engler (ETH Zurich), the lead author of the study. “The resulting images show 51 debris disks with a variety of properties — some smaller, some larger, some seen from the side and some nearly face-on – and a considerable diversity of disk structures. Four of the disks had never been imaged before.”

Comparisons within a larger sample are crucial for discovering the systematics behind object properties. In this case, an analysis of the 51 debris disks and their stars confirmed several systematic trends: When a young star is more massive, its debris disk tends to have more mass as well. The same is true for debris disks where the majority of the material is located at a greater distance from the central star.

Arguably the most interesting feature of the SPHERE debris disks are the structures within the disks themselves. In many of the images, disks have a concentric ring- or band-like structure, with disk material predominantly found at specific distances from the central star. The distribution of small bodies in our own solar system has a similar structure, with small bodies concentrated in the asteroid belt (asteroids) and the Kuiper belt (comets).

The data from various telescopes both on the ground and in space is increasingly telling us that our solar system is not unique, and that the galaxy is filled with millions of similar systems, all in different states of formation. This hypothesis is further strengthened by the appearance of interstellar comet 3I/Atlas, which despite coming from outside our solar system is remarkably similar to the comets formed here.