The global launch industry in 2025: The real space race is between SpaceX and China

In 2025 the worldwide revolution in rocketry that began about a decade ago continued. Across the globe new private commercial rocket companies are forming, not just in the United States. And across the globe, the three-quarters-of-a century domination by government space agencies is receding, though those agencies are right now pushing back with all their might to protect their turf.

Dominating this revolution in 2025 in every way possible however were two entities, one a private American company and the second a communist nation attempting to imitate capitalism. The former is SpaceX, accomplishing more in this single year than whole nations and even the whole globe had managed in any year since the launch of Sputnik. The latter is China, which in 2025 became a true space power, its achievements matching and even exceeding anything done by either the U.S. or the Soviet Union for most of the space age.

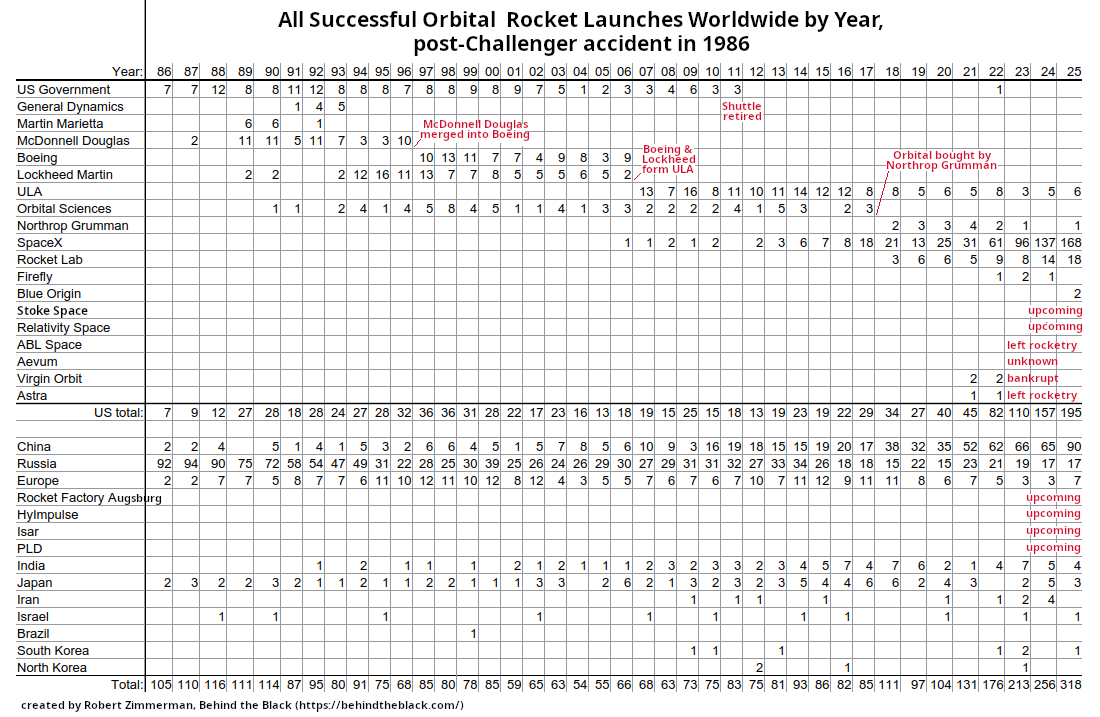

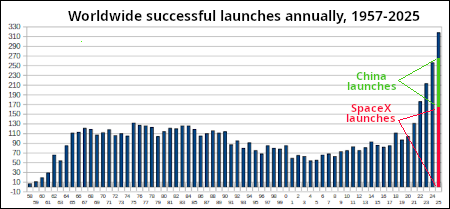

The table above shows all successful launches globally since 1986. I picked that year because that was when, following the Challenger accident, that President Reagan ended all commercial flights on the space shuttle, declaring that future commercial launches must be done by private enterprise, not a government agency.

Since then there has been a slow growth of American rocketry, though Reagan would certainly have been disappointed at how long that growth took to get started. For three decades following Reagan’s edict only one new American rocket company appeared, Orbital Sciences, while the other established big space companies either consolidated or disappeared. Above all, none of these old companies seemed at all interested in innovating or lowering costs. Instead, they almost completely relied on big government contracts from the military and NASA, allowing the commercial market to drift across to Russia and Europe.

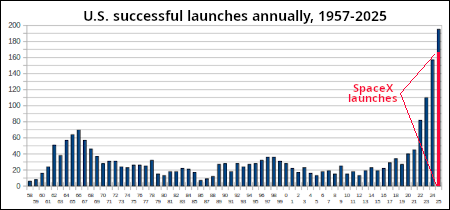

And then came Elon Musk and SpaceX in the late 2000s. Though it took a decade, by the mid-2010s SpaceX’s launch rate began to take off. And in 2025, that launch rate exploded. The graph to the right illustrates this. While the U.S. in 2025 smashed its previous annual launch record with 195 launches (almost triple the 1960s record of 70 that had lasted until SpaceX came along), 86% of those American launches were by SpaceX.

Nor did SpaceX dominate just the American launch industry. Its 168 launches in 2025 exceeded that of the rest of the world combined. Moreover, it put into orbit more than 90% of all payload mass.

In many ways the effort by space agencies and governments worldwide acts to hide SpaceX’s dominance. News outlets tend to focus on government space programs as if only those programs really count. Thus, the media sees the race between China and NASA to get humans back on the Moon as the whole story.

Superheavy captured safely yesterday by the chopsticks,

for the third time in four attempts, on March 2025

In reality, the real American space program right now is SpaceX’s, and it is the one truly racing China in space. It is not only building the biggest rocket ever (Starship/Superheavy) to create its own Mars exploration project (with a side effort on the Moon), it is doing so on its own dime. SpaceX presently is almost entirely funded these days by revenue produced by its rockets and its Starlink constellation. The latter is adding about 20,000 new subscribers per day, and is pulling in revenue in excess of $8 to $9 billion per year. Combined with previously raised investment capital, SpaceX actually has a real budget almost comparable to that of NASA’s. It might be about half in total, but that half is far more effectively spent.

If the U.S. is going to beat China in space, it is only going to do at this time with SpaceX. NASA’s effort is not only irrelevant, it is trivial in comparison. The best its Artemis program will do is repeat an Apollo 11 landing, an achievement that historians will consider a minor footnote in the settlement of the solar system. It will be what SpaceX does in the next decade that will go down in history as historic and significant.

Before moving on to China, 2025’s other dominant player, we must note the pluses and minuses of the rest of the American rocket industry. Rocket Lab for example finally began to achieve a reliable and fast launch rate for its Electron rocket. All signs indicate that it will likely begin launching twice and even three times a month in 2026, especially because it plans the first launch of its larger Neutron rocket early next year. Blue Origin in turn finally got its New Glenn rocket off the ground, with two successful launches and a successful landing of the first stage on the second launch. Expect it to slowly ramp up launches in 2026, though it is not likely it will match Rocket Lab’s launch rate for several more years. Finally, ULA got its new Vulcan rocket operational in 2025, and appears poised to finally begin a steady launch rate of more than once a month in 2026.

The remainder of the American rocket industry remains an unknown. Firefly had one launch failure and lost a second rocket during a static fire test, so it completed no launches in 2026. Similarly, Northrop Grumman’s plans have been stymied because its Antares rocket is grounded until Firefly (which is providing a new first stage) can get off the ground.

The other rocket startups are either dead, or in development. Though no launch dates have been set for either, it is expected that both Relativity and Stoke Space will attempt a first launch in 2026. Their entrance into the market — along with the addition of Rocket Lab’s Neutron and the ramp up of Blue Origin’s New Glenn and ULA’s Vulcan — might finally force SpaceX to face some competition.

One last point about the U.S.: For the first time in years, in 2025 government regulation and red tape became a non-issue. The Trump administration has effectively shut down the effort by the administrative state — enthusiastically encouraged by the unknown players who ran the Biden administration — to impose its will on everything and everybody. In the U.S. freedom ruled more than anything last year, and for this reason we saw real progress across the entire industry. Sadly, that progress was mostly an effort to make up lost time.

China and Russia

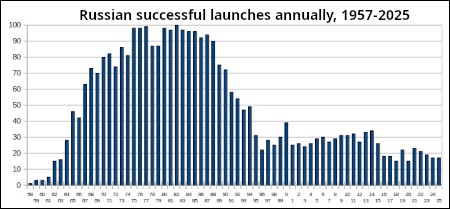

For the past decade the rocket industries of China and Russia have been like two elevators moving in opposite directions, one going up and the other down.

As the graph to the right shows, Russia (before the fall of the Soviet Union) once dominated the global launch industry. Many of the those Soviet launches however were done to maintain ineffective jobs programs. When the Soviet Union fell those launches ended.

Beginning in the mid-1990s and into the first decade of the 21st century Russia’s launch industry however experienced steady growth, partly because it was now free to compete for satellite business in the west, and the American launch industry had no interest in fighting for that market share.

That growth ended under Putin, for two reasons. First, Putin consolidated the industry into a single government-owned corporation, Roscosmos, ending all competition and thus squelching any incentive for innovation or efficiency. Second, Putin invaded the Ukraine, ending Russia’s access to the western satellite market, losing in one fell swoop billions in income.

In the past decade most of Russia launches have been limited to maintaining (barely) its domestic and military satellite constellations, and flying a few manned and unmanned missions each year to ISS. And though it claims it will launch its own station after ISS is retired, don’t bet on it. Without a major reformation, it is very possible Russia’s participation in space will shrink to practically nothing in the coming years.

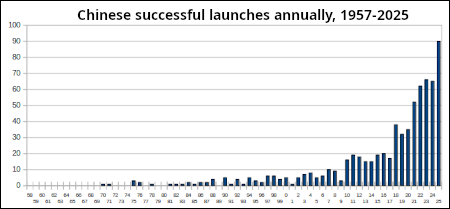

China’s rocket industry meanwhile has boomed, and it has done so by adopting policies directly opposite to that of Putin. It has allowed the formation of what I call pseudo-companies, which mimic capitalism by working independently while competing for contracts and profits. All are under close supervision and control by the communist government, which can take them over at any time, but this system allows for competition which thus encourages innovation and efficiency.

As a result China in 2025 set a new record of 90 launches. Furthermore, two different rocket designs attempted to land their first stages for later reuse. Both attempts failed, but we should expect China to successfully land one or more rockets vertically in 2026. It also has its own functioning space station, continually occupied, and has been encouraging independent pseudo-companies to develop their own capsules and cargo freighters to supply it.

Whether China’s success will continue remains uncertain. As a top-down political system, it could all end in an instant if there is a major change in leadership and policy. Barring that, its space program is well thought out, carefully planned in a very rational manner, and has been hitting its planned milestones now with some regularity and few delays for more than a decade. Expect that to continue in 2026 and at least the next few years. Beyond that no one can predict.

On the periphery

The rest of the world’s rocket industry falls into three categories: Europe, India, and everyone else.

In Europe the last three years have seen a major change, with Germany, France, Italy, and Spain all abandoning support for the European Space Agency’s (ESA) government-run Arianespace operation by taking management of the French Guiana spaceport and the Vega-C rocket from it. It is also no longer involved in designing or building new rockets. Instead, these European countries have thrown their support to new private competing rocket startups. None have yet launched, though the German startup Isar had a failed launch attempt in 2025. Isar has a second attempt scheduled in only two weeks, while the Spanish startup PLD is targeting a first launch in ’26. The German startup Rocket Factory Augsburg was close to launching in 2024, but after an explosion during a static fire test destroyed the rocket little has been heard from the company.

The one operational private rocket company in Europe right now is Italy’s Avio. Its regained control of its Vega-C rocket from Arianespace as part of this shift in policy, and has been winning launch contracts since. Expect it to show major progress in the next two years.

Arianespace still manages the Ariane-6 rocket, but as an expensive expendable rocket its future is limited. It has a multi-launch contract to place many of Amazon’s Leo satellites in orbit, but after it completes that work it will be difficult for it to garner new business.

Whether Europe will succeed in this transition to the capitalism model remains unclear. Its bureaucracy is very firmly entrenched, and appears working hard to make sure it controls everything the new private companies do. I suspect the real turning point will be when one of these rocket startups successfully launches. That was the turning point in the U.S., when SpaceX finally succeeded.

In India, the situation is very similar to Europe’s. The Modi government has been pushing to reduce the power of its space agency ISRO, demanding it transfer ownership of rockets and operations to the private sector. That bureaucracy however has done a good job maintaining control, cleverly restructuring programs designed to shift ownership to the private sector so that the shift really doesn’t happen.

Meanwhile India has a handful of rocket startups, with two (Skyroot and Agnikul) appearing to be close to a first launch. It will likely take a launch success in India as in Europe to make real change possible.

Finally there is everyone else, most of which are third world countries publicizing grand plans with little likelihood of success. In Arabia both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have made progress, but both are far from becoming space-faring nations.

Japan is likely the world’s biggest disappointment. Despite being a first world nation of high technical capabilities, its entire space industry is controlled by its space agency JAXA, which has done a very poor job building rockets and spacecraft. The few private startups that exist have had trouble getting off the ground, with only the lunar lander startup Ispace having any success, though that success has only been in garnering investment capital and contracts. Its only two lunar missions both crashed on the Moon.

Conclusion

The graph to the right shows us that, unless some unforeseen catastrophe occurs, the future of space travel is now brighter than it has ever been. The graph might suggest everything is now controlled by SpaceX and China, and that little else is happening, but that is wrong.

Competition fuels everything, and right now the competition between SpaceX and China quickens everything they do. In addition, China’s successful space program to return to the Moon is spurring the U.S. government to promote its own space effort, if only to feed the egos of the blowhards in office.

SpaceX’s domination in the U.S. is also spurring the nation’s many new and old companies. They want a piece of the pie, and if SpaceX can make so much money from its space assets, why can’t they?

The success of both SpaceX and China is also inspiring governments and entrepreneurs worldwide. There is both literally and figuratively a vacuum in space, and every nation wants in. And since SpaceX and China have demonstrated that competition and private enterprise are the way to go, every nation in the world is trying to copy that model, in some form or another. This competitive urge even applies to the small peripheral nations. Many might not be close to success, but all are pushing hard to get there. Under these conditions, success is sure to follow.

In creating this last graph this week, I found I had to expand the vertical axis, since 2025 was the first time the world had ever exceeded 300 launches in a single year. I fully expect to have to expand that axis again and again in the coming years. In fact, I fully expect the numbers to easily top 400 before we reach 2030.

And that’s only the beginning. From that moment these numbers should truly skyrocket, to a point it will no longer be practical keeping count. Only then will humanity truly become a space-faring civilization.

Hold on tight. It is going to be quite a ride.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

It might be useful at some point to break tracking of SpaceX into Falcon and Starship. And speaking of Starship, you’ve been counting the successful launch-and-return as part of the SpaceX count, but so far these have been sub-orbital flights (noting that as a booster, SuperHeavy is fully capable of orbital launches). You aren’t counting anyone else’s suborbitals.

Diane Wilson: The issue of including the Starship flights in my count was discussed at great length previously here. I admit it is open to disagreement. I also admit it is my personal choice.

It won’t matter I think in ’26, as SpaceX is about to go orbital on these flights.

As for keeping count of individual rockets, that’s not the point of my work here. I am not trying to document every detail of the launch industry. Instead, I am trying to determine which companies or nations are succeeding the most in getting anything into orbit.

Moreover, I don’t want to increase my workload on this, as I wish to cover other things as well.

Mr Z:

You link to an item claiming that SpaceX “put into orbit more than 70% of all payload”. He’s measuring “payload capacity”.

If you instead look at actual mass carried to orbit, SpaceX is even more dominant: SpaceX carried 90% of all mass to orbit in 2025.

https://x.com/XFreeze/status/2006507841050521816

In other words, that’s nine times more than the rest of the world, combined. Astonishing what those capitalists can accomplish, isn’t it?

Steve Golson: Thank you for this better graphic. I have revised the essay to include your link rather than the first one, which I also though was somewhat unclear and not as correct. It was what I had at the time.

Hello Bob,

Nice summary (as always).

“As the graph to the right shows, Russia (before the fall of the Soviet Union) once dominated the global launch industry. Many of the those Soviet launches however were done to maintain ineffective jobs programs.”

Wasn’t most of that for military satellites? I don’t have time to dig into the launch stats, but…the Soviets were forced to launch lots of those because they were usually very short-lived.

Richard M: The bulk of the Soviet Union’s high launch totals from the 70s to 80s were for short-term surveillance satellites that stayed in orbit mere weeks. That technology was used by the Pentagon for only a few years in the early 60s, and abandoned for high-res CCD tech on long-life satellites in the 70s.

Hi Steve,

Did X Freeze run the numbers for that pie chart?

I asked Grok what percentage of SpaceX mass launched was Starlink -80%. It took 4 minutes and it obviously had trouble with variable starlink satellite mass.

I thought it relevant in terms of the ‘great power competition’ between the US and China. The US is building an internet constellation while the Chicoms are…. probably military heavy in their launches.

Good point Diane

In the same way that there is a disconnect between the X-37 and MAX guys at Boeing—there is something up with the Starship guys.

Falcon is about as dialed in as anything I have ever seen.

The best outfits (public, private, whatever) have a culture of work.

Towards the end of this Adam Savage video, there is what I would consider a priceless collection of late 1800’s magazines actually called “WORK:”

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=_jiu61PCgHs

This was by, and for, a *community* of people…human capital.

If I saw that stack of crumbling newsprint–and was told that if I burned it I would receive a pile of emeralds–I’d put those gems in the fire instead.

Look at the care that went into those illustrations. That collection is more sacred to me than that grail Adam holds even if it was real. Tool Time’s grimoire.

China is trying to build a little MAD MEN ethos. Here in the states, taxpayers were PROUD of their money going to bright citizens, yet MSFC receives not an atta’ boy but attitude.

China isn’t making that mistake:

https://phys.org/news/2025-12-tokamak-exceed-plasma-density-limit.html

They remind me more of what 1950’s America USED to be.

Jeff Wright,

Anent engineering, the Starship guys are the Falcon guys. You keep trying to pretend that SpaceX is actually two separate companies. It isn’t.

Nobody with sense gives any attaboys to MSFC because they haven’t done anything to deserve any in decades. Either the MSFC guys are not the best and brightest or they’re working way below their potential. I’ll let you decide which of those alternatives is the worse.

I am looking forward to April–their worth will be evident to the world then.

One more thought on this, and it’s the Big Thought. You cannot help but look at Mr. Zimmerman’s chart and graphs, and ponder where the United States would be right now had Elon Musk decided to use his PayPal millions to just pursue electric cars in 2002 and just give rockets a pass. And shudder.

Because it would be yet one more area of advanced industrial activity where the PRC would be kicking our rear ends. China might or might not be facing imminent demographic armageddon, but even if they are it is no less humiliating that the Chinese shipbuilding industry pumped out over 1,000 ships last year, as against America, the country that obliterated the Empire of Japan by spamming out not just aircraft carriers but also ice cream barges within living memory, ended up building….just six. With no SpaceX on the scene, the United States would look almost as humiliated in space, too, with most of its launch activity still consisting of the usual dozen or so gold-plated ULA milsat launches, struggling to get its humans to orbit reliably in a balky Boeing space capsule, and without even a dream of Starlink. With all the rest of the knock-on effects for the U.S. space industry that implies.

But we do have SpaceX. And that changes everything.

Riffing on my last comment about U.S. shipbuilding, today brought more depressing news from the Bay Area: “Vallejo city officials say they’ve been informed that the Mare Island Dry Dock will be closing permanently and laying off all workers.”

https://www.cbsnews.com/amp/sacramento/news/vallejo-mare-island-dry-dock-closing-layoffs/

Mare Island closed its shipyard in 1996. Now they’re even closing the dry dock. You can blame some of this on California’s radioactive business environment if you like, but it’s clear that the causes here are also deeper and nationwide. If I’m not mistaken, the only dry docks the US Navy has access to in WESTPAC now, even theoretically, are the ones remaining at Puget Sound and Pearl Harbor. He might be laying it on a bit thick, but cdrsalamander has reason to be rueful when he says, “This is what a dying naval power looks like.”

Makes you wish, just a little, that Elon Musk was into shipbuilding.

Dick Eagleson

“”””January 1, 2026 at 10:19 pm

Jeff Wright,

Anent engineering, the Starship guys are the Falcon guys. You keep trying to pretend that SpaceX is actually two separate companies. It isn’t.

Nobody with sense gives any attaboys to MSFC because they haven’t done anything to deserve any in decades. Either the MSFC guys are not the best and brightest or they’re working way below their potential. I’ll let you decide which of those alternatives is the worse.””””

I’d say that $4B-$5B a year is a heck of an attaboy.

Neither they nor the ABMA (which what Marshall was) had anything like LeMay or Rickover budgets, or we’d have a Moonbase today.

To Richard M

There are only a handful of folks in America who know how to weld armor….shipyards are a sore point with me as well.

Speaking of China, while Elon runs from hydrogen, they embrace it:

https://techxplore.com/news/2026-01-demand-hydrogen-fuel-production-dark.html

This isn’t me doing a Gary Church and quoting Mao—this is me wishing America could get our can-do mojo back.

America has suffered from bipartisan stupidity. The Greens in California and libertarians have BOTH done a number against American industries.

Jeff Wright,

Artemis 2 isn’t going to be any demonstration of MSFC’s “worth.” At best, it may demonstrate that, after 3-1/2 years, it has figured out a way to barely squeak by the engineering failures that attended Artemis 1. At worst, we’ll be chiseling four more names into the Astronaut Memorial and awarding four more posthumous Space medals of Honor.

I would prefer the first outcome. I would prefer it even more were it to eventuate without any crew put at risk. Let us hope Jared sees the wisdom of making Artemis 2 another uncrewed test run.

The reason a military Moon base effort never got a LeMay or Rickover-class budget is because – unlike jet bombers and nuclear subs – it would have had no military utility and was, in any case, proscribed by the Outer Space Treaty of 1967. One of these things is not like the others.

If the PRC wants to chase after hydrogen, let it. Hydrogen as a fuel is a fool’s errand – something now uniformly acknowledged by Western automakers who have entirely abandoned it.

Is there any form of ridiculous engineering you will not cheerlead for? The world wonders.

john hare,

Boeing and Lock-Mart get the majority of that annual $4 – $5 billion. The rest, which goes to MSFC paychecks, is more inertia than attaboy I’d say.

Richard M,

Yes, absent Musk, the US would be in a world of hurt anent space. That’s an alternate universe I am very happy we do not inhabit. 2025 was our best-ever space year. 2026 is shaping up to be far better. The future’s so bright I gotta wear shades.

US naval shipbuilding is very much in shambles and civilian shipbuilding at any significant scale is pretty much dead. I offered some ideas about how to fix the former awhile ago over on Rand Simberg’s blog. But the way things are going, the US may well be out of consequential enemy nation-states before anything – my solution or any other – could be implemented to rationalize naval construction.

Hello Dick,

I don’t think that the United States has ever had such a consequential industrialist — not even Ford or Edison. The scary thing is, a decade from now that might be exponentially more true.

I never saw your shipbuilding comment, but if you have a link, I’d be happy to read it.

Jeff Wright,

You wrote: “this is me wishing America could get our can-do mojo back.”

America still has a can-do mojo, but it has moved from NASA and Congress to several U.S. companies. SpaceX’s can-do is so powerful that they succeed at doing the impossible, most of the time. Rocket Lab is also showing its can-do spirit as well as Stoke Space and several other launch companies. Then there are the space operators that are already flying or are soon to fly. Varda has already shown it can manufacture in space (but it cannot convince the cannot-do American government to let it return its space products). How many companies are working on space stations? Talk about can-do, Vast is getting ready to fly its first version to orbit.

Hydrogen as a propellant has its advantages, but it also has its limits. For some uses, the limits overwhelm the advantages.

You look to Marshall Space Flight Center, do not see a can-do attitude, and assume that the rest of America has lost it, too. Your viewpoint is a bit myopic. You may want to expand it and look at the whole of the big picture, or at least more of the bigger picture.

To riff a little more on both my observation and Edward’s here, Ken Kirtland whipped up a useful graphic showing orbital launch attempts for 2012-2025, with a focus on China and the United States, both with and without SpaceX:

https://x.com/KenKirtland17/status/2006458197356257480

And he makes an observation similar to that which Edward makes: “I think this graph also helps give us a picture of how healthy the US launch market is outside of the elephant in the room. Growth has not been impressive the past 23 years. But I think that is about to change. With Electron contiuing to increase cadance, New Glenn coming online, and Neutron etc behind that, ~2025 will likely be the start of the “USA without SpaceX” line climbing rapidly.”

I think he’s right, too. This is the sign of an increasingly vibrant U.S. launch industry.

Hello Jeff,

“Speaking of China, while Elon runs from hydrogen, they embrace it:”

Well, yeah, Chinese researchers may be embracing hydrogen *production*, but are they really going to use it much for propellant in coming years?

LandSpace’s Zhuque-2 is methane-powered.

Long March 9 will be methane powered.

Korean Air/Hyundai’s Rotem will be methane powered.

So is Rocket Lab’s Neutron.

So is Blue Origin’s New Glenn (booster stage).

So is ULA’s Vulcan (booster stage).

So will be Relativity Space’s Terran R.

So will be iSpace’s Hyperbola-3.

And the list goes on.

So many new players are pursuing methane rather than hydrogen for their first stages — it might be worth asking why that is.

Richard M noted: “So many new players are pursuing methane rather than hydrogen for their first stages — it might be worth asking why that is.”

If it helps Jeff, or anyone else who is curious, Tim Dodd, The Everyday Astronaut, did a video that included the difference and usefulnesses of hydrogen vs methane vs kerosene, another popular first stage fuel. This may give the answer, if you were thinking of asking the question:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LbH1ZDImaI8#t=1200

Scott Manley has his own version of why SpaceX chose methane for Raptor:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4pzgFHrLXmc

Methalox is a compromise of energy density and specific impulse..a compromise.

The two propellants are close in temperature.

With kerolox you just need the oxidizer cold.

Another reason I want Marshall kept alive—to keep North Alabama from becoming puke blue:

https://www.wbrc.com/2026/01/03/no-war-oil-protesters-gather-huntsville-after-strikes-venezuela-maduros-capture/

All Birmingham was ever good for was protests—-but things are changing.

I don’t want folks from Colorado here. That’s Trump’s big mistake..

The “let them eat cake” libertarians are going to trigger a blue wave…so you lot just keep it up.

There will be worse than MSFC to deal with.

The voting public is fickle.

I guess it didn’t help Jeff after all.

Jeff Wright,

I thought you were referencing hydrogen anent ground transport. My bad. But, in a away, you were referencing hydrolox for starting-at-ground-level transport.

For boosters, methalox isn’t really a compromise. It allows for a much smaller and lighter booster structure than does hydrolox and provides nearly the same sea level Isp. Hydrolox boosters usually require big-ass SRBs to get them off the pad – e.g., Ariane 6 and SLS. The only hydrolox launchers that could levitate on hydrolox alone were the Delta 4 and the Japanese H-2 & 3 and most of the time they used SRBs as well. Hydrogen’s Isp only shines in vacuum. Stoke, ULA, JAXA-Mitsubishi, Arianespace and BO are still doing hydrolox upper stages for exactly that reason.

SpaceX went with all-methalox-all-the-time for Starship because it needs to operate between Earth and Mars. Methalox is easier to make and store on Mars than is hydrolox.

Oh yeah, the fact that the two cryo components of methalox have similar boiling points just makes it easier to engineer common dome tankage. Everything shrinks and expands at the same rates and one doesn’t need a lot of insulation to keep the fuel from freezing the oxidizer.

This is what I find worrisome:

https://www.reddit.com/r/SpaceXLounge/comments/hi5a6w/will_starship_forgo_oxygen_superchilling_to/#:~:text=The%20freezing%20point%20of%20methane,temperature%20of%20the%20liquid%20methane.

That’s a close thing.

I liked Beal’s approach in that both liquid propellants are pretty much room temperature, but the carbon fiber wouldn’t like that HTP.

O/T

I am surprised the AP ran this

https://apnews.com/photo-gallery/venezuela-us-explosions-caracas-25a01a23e7b936b430901428ab0d0907

That’s different.

Jeff Wright,

You should have read the top two posts; they point out that SpaceX has already tackled the problem and that the solution is simple.

To the original post: “NASA’s effort is not only irrelevant, it is trivial in comparison.” I find this unfortunate, especially the enthusiasm some show for NASA’s diminishing role. It seems that as long as they get their way, they do not care whether NASA remains relevant to American spaceflight.

“In the U.S. freedom ruled more than anything last year, and for this reason we saw real progress across the entire industry. Sadly, that progress was mostly an effort to make up lost time.” Let us hope that future administrations keep this up, and continue to hamstring the administrative state until it can no longer constrict us in the name of faux ‘safety’ and ‘diversity.’

Nate P: I have spent more than forty years watching NASA achieve almost nothing in manned space flight, following the Apollo landings. It has been a failure, and a failure that has only gotten worse with time.

In business, failures go bankrupt and are replaced by competitors who can get the job done. The time is long past for this process to happen to NASA.

Again, American Space prowess needs to be more like the USAF than Braniff.

The recent takedown of Maduro didn’t require begging VCs for cash:

https://breakingdefense.com/2026/01/venezuela-150-aircraft-cyber-effects-maduro-operation-how-it-happened-caine/

Musk and Bezos have close to two trillion bucks—far, far more than SLS…and MSFC is going to embarrass both of them in short order…assuming no one named Jared slashes the tires of our bus.

Robert Zimmerman: yes, I agree. I was referring to what some commenters written here, not your post. My apologies for the confusion. NASA is too sclerotic and bureaucratized to be very effective, and I am not sure Isaacman can turn the agency around. I’d like that to happen, but even then I think NASA should not be an operational agency anymore.

It’s bracing to recall that Jerry Pournelle was most immediately inspired by the state of NASA when he formulated his Iron Law of Bureaucracy. And that was the NASA of the 1980’s and 90’s, not the NASA of today!

Some of us here would argue that the most important and valuable thing that NASA’s manned spaceflight program has done since then, ironically, is to enable the rise of SpaceX, via COTS (2006), Commercial Resupply Services (2008) and Commercial Crew (2011-2014) awards. And all of those programs had to overcome serious entrenched opposition within the agency before they happened.

Ellie In Space recently interviewed Joe Tegtmeyer, and he said that 2026 is the year of execution, that everyone needs to execute on their plans, meaning that it is time to get things done. Vast is about to fly its space station, Starship is on the verge of orbital flights and with it will come the first payload deliveries by that spacecraft, and Rocket Lab is getting ready to introduce Neutron. Can more lunar landers succeed in landing on the Moon? Can Starliner work right, this time? This would be a good year for all these launches to start paying off in a big way.

I indended to include this with my previous post:

Nate P,

I have recently started advocating for NASA to transform its function into something more like the NACA, which had a mandate to be useful for the American aerospace industry (before there was the space part), not an agency that is in competition with the American aerospace industry. An example is wind tunnels, which NACA provided, because they could be far too expensive for individual aircraft companies to own.

The NASA history includes the exclusion of commercial space companies. It is unfortunate that government regulated an independent American commercial space industry out of existence. NASA was the sole provider and supplier for several decades, and even when the government relaxed its stranglehold on commercial space, it was difficult for the industry to find investors. Kistler Aerospace is a good example. It was not until Orbital Sciences and SpaceX were successful that investors began to take some risks in commercial aerospace.

Governmental interference or control is still a major factor in the ability to operate in space. Governments have other concerns that distract them from space, but space companies can remain focussed on their corporate goals: to explore or to utilize space in a way that we earthlings will pay them for. A government has other goals: To defend its citizens and their rights and to peaceably resolve disputes as an indifferent third party. Space is a distraction from these two primary purposes for government, so we should not be surprised that their space programs are underfunded and poorly run. Governments were also meant to stay out of the way of their citizens, but many have forgotten that they, the governments, are not the sovereign, the citizens are, and the government was created to be of service to the citizens, not to be the ruler. This lapse of memory is why governments created space programs that left out the citizens — civilians were prevented from participating in space, and that was the intent of the Outer Space Treaty, created and enforced by governments.

When civilians, through space companies, are able to develop their own space vehicles or their own experiments with a minimum amount of government interference, we have seen that they do very well. Rocket Lab, SpaceX, and Virgin Orbit are good examples, where the last example also shows what happens when government unexpectedly hampers operations.

__________________

Robert wrote: “In reality, the real American space program right now is SpaceX’s, and it is the one truly racing China in space. It is not only building the biggest rocket ever (Starship/Superheavy) to create its own Mars exploration project (with a side effort on the Moon), it is doing so on its own dime.”

This brings up two more points that are especially important. They may be in a race in space, but I don’t think either one thinks that they are in a race with each other. China undoubtedly thinks it is racing NASA, if it thinks of itself as being in a race to the Moon, and Congress definitely thinks that it is funding NASA at a level that allows it to beat China to the Moon. SpaceX, on the other hand, is racing NASA for readiness with its, SpaceX’s, contractual obligation for a lunar lander under the HLS project, and SpaceX’s other interest in the Moon is for development of a source of materials for its own needs to make and supply its own future spacecraft that will provide products for we earthlings — products that we will pay for. For that second SpaceX interest, they are in a race with time, if they are racing at all.

The second point is the independence from government and its taxpayers. Doing space exploration on its own dime allows a company to choose where and how it wants to explore, and what and how to supply products that we earthlings will pay for. When the taxpayer pays, he gets upset that one company (or more than one) may profit from his tax dollar, so the government sets rules, regulations, and laws that restrict what, where, and how the taxpayer dollar is used. Thus, the ISS has not produced anything that lets the American taxpayer feel good about funding such an expensive National Lab.

On the other hand, Starlink was funded exclusively with investor money, and right now 20,000 new subscribers a day feel good about being able to pay for and use that service. If it fails, no taxpayer money was wasted, and if it succeeds, taxpayer money didn’t go toward anyone’s profits. Profits are the reward for improving the efficiency of production, and Starlink is an improvement over Iridium and GlobalStar, which were improvements over geostationary communication satellites, although not quite so efficient as to win out over the cellular telephone.

The revolution in rocketry has had an effect on the world’s launches, on who is doing the launching, and on who is being launched into orbit.

______________________

Richard M,

Your linked X post is instructive. I agree that two of our operational launch companies are about to take off in a way similar to SpaceX. Rocket Lab has used rapid development in the same way as SpaceX, but Blue Origin took a little longer to get there, and I hope that Firefly is also able to get back on the scoreboard and ramp up, too. A couple other American companies are approaching first successful launch and operations, Relativity Space and Stoke Space. Hopefully, other companies around the world will also get on the scoreboard and become relevant launchers, too.

Stralink – 5 years ago it was making zero profit. They had 4.6 million customers in December 2024. They have 8 million December 2025. I expect 12-15 million customers in 2026. Maybe $20-25 billion in revenue in 2026. That is equivalent to Nasa’s budget. Plus, whatever SpaceX makes off everything else they do (I think it is a couple of billion $).

The entire starlink constellation cost maybe $19 billion to build and launch. The entire cost of starship development was around $5 billion. Final estimates are as much as $10 billion. That includes building the entire factory to make starships, and two launch towers. But starlink basically will cover all costs and pay back all investment.

Once starship is fully operational, and I see no obstacles, within 5 years, nothing will be even close to competing. Cost and safety are directly tied to how often you do things. When you launch 130 times a year, you are racking up the experience points very rapidly. Cost go down; safety goes up.

And, thing is, once you have starship functional, every other rocket launch system makes zero sense. It can do anything you need, anything you can conceive of. Also, once star link is full active, launching a competitor becomes an expensive waste of time – most people will have bought into star link, and they will have a substantial first mover advantage.

The race is already over, and most people don’t know it. Maybe Blue Origin can get a piece, maybe rocket lab. China will launch, but who will contract with China for launch services other than the Chinese? The EU, if they are smart, will simply start launching with Space X for everything. Same with Japan, Korea, etc.

Starship is a quantum leap from Falcon 9, and most companies out there are still trying to build their own version of a falcon 9. Starship will make falcon 9 superfluous. And this will happen in 5 years…at most.

Geoman,

You seem to have an attitude that SpaceX and especially Starship are the answer to most questions. Starship is being developed for around $10 billion. Around April of 2022, SpaceX said they had already spent about $3 billion, and shortly after that they said they planned to spend $2 billion per year, so in April of this year they should hit the $9 billion mark, assuming a constant spending rate. The cost per pound to low Earth orbit (LEO) should be fairly low, relative to today’s launch market, perhaps $150 per pound, around the price to send a one-pound package from San Francisco to Paris, overnight. She may be able to lift 200 or maybe as much as 250 tons to orbit, and if they charge as low as $20 million per launch, then the price would be ($20 million / 500,000 pounds =) $40/pound.

Not too shabby, unless you only wanted to send 500 pounds to a specific orbit unique from any other satellite, then a $6 million launch on a small launch vehicle would be much better for you. One size does not fit all. A major benefit of having multiple companies and multiple space products is that customers can find the size that fits them for the price they can afford.

In another thread you wondered why build space stations when Starship can be its own space station.

https://behindtheblack.com/behind-the-black/points-of-information/the-space-station-race-startup-max-space-to-establish-factory-at-kennedy-in-florida/#comment-1627124

Starship would make a perfectly acceptable space station.

https://www.space.com/nasa-considering-spacex-starship-space-station

There are limitations, however. Starship was designed for a specific mission — colonize Mars — and it will also raise revenues through other missions that it can perform, such as land on the Moon and take payloads to LEO. However it is not ideally suited for many of the missions that people want to use it for. It is not designed as a long-duration space station, the way that ISS was. It could easily perform missions similar to the Space Shuttle, perhaps with six-month missions (the time it would have to work in space to get to Mars), lower cost, and more capacity for science. I’m sure that SpaceX will perform at least one dry-run mission in LEO in order to test Starship’s ability to function for the duration of a trip to Mars. That mission will look a lot like a space station mission or a long-duration Space Shuttle mission.

Think of having a semi-truck and using it for everything that you do. It can take you to the grocery store (analogous to a lunar landing), but it is not ideal for that task. You can use it as a camper (space station), but it is not ideal for that task, either. Commute to work? Not really. Hauling large or heavy loads long distances? It excels at that, but that excellence may also depend upon the payload. If it is a box truck or trailer, then hauling earthmoving equipment may be difficult. If it is a flatbed, then moving groceries from the warehouse to the store may be difficult.

As for Starlink, a competitor would keep SpaceX honest. If SpaceX is a monopoly, then it could get greedy and charge so much that customers begin to shy away. Business school teaches the concepts of “all the market will bear,” and finding the price point for maximum profit before too many customers stop using your product. Both of these philosophies cost the customer more than necessary, resulting in customers having less money to spend elsewhere. Customers may even choose to leave the market and spend their money or move their business model to some other market or industry. Competition will keep SpaceX from charging too much, and may force it to reduce its current prices.

SpaceX, in designing Falcon, Dragon, Starship, and Starlink left some efficiencies on the table. Despite the way it looks, none of these spacecraft are the be-all do-all end-all of space travel. Other companies can find better efficiencies and still compete with SpaceX. This is why they have not all packed up and gone to other industries.

SpaceX has done some amazing things, and I applaud them for making space actually popular, not just something to talk about, like we did in the 1960s and 1970s. We thought that the Space Shuttle would open up space in the 1980s and were sorely disappoint when that failed to happen. Now we have several companies that are in the space business for the purpose of growing the space business, and that is a good thing.

I think Starship has a lot of potential, and it doesn’t need to be the most efficient option in every scenario, just efficient enough; but neither will it sweep all competitors away. Falcon 9 is cheaper than the competition, yes, but other launch companies are still getting contracts, and SpaceX hasn’t passed all of their internal savings to external customers. There’s no real pricing pressure on them yet. I’ve read rumors that Starship contracts are currently being offered at $100 million, which is a great deal if you want to loft a hundred tons to orbit. Not everyone does, though: Stoke Space has signed agreements with AstroForge for multiple launches; what the latter needs isn’t megatons to orbit, it’s cheap high-energy launches for lightweight payloads.

I won’t be surprised if Starship ends up carrying over 95% of mass to orbit while there are no vehicles in its size with a competitive price tag, but I think they’ll come; and there will be a demand for vehicles of many other sizes-the key point will probably be full reuse, to amortize costs over numerous launches, and to cut expenses versus having to manufacture new hardware continuously just to operate.

If SpaceX is a monopoly, then it could get greedy and charge so much that customers begin to shy away.

I’ve wondered where that price point is for me.

My cell phone bill as about the same as my Starlink bill, which is about the same as my wired/cable internet bill. I have no clue where my cell phone or cable payment is going. I know where my Starlink payment is going and I’m happy to pay a premium to support space development. At what point does that happiness turn into anger at the cost? I don’t know.

The reason I have two internet providers is that I work from home and need a reliable connection – and I have a tenant locked into the cable connection so the Starlink bandwidth is all mine. Both Starlink and the Blue Peak (cable) connections have occasional issues, but Starlink has gotten MUCH better over the past few years.

That argues that the tipping point “should” be around double what it costs now. I don’t know that I’d put up with double (leaving aside inflation).

Nate P wrote: “I’ve read rumors that Starship contracts are currently being offered at $100 million, which is a great deal if you want to loft a hundred tons to orbit.”

That would be $500 per pound, which is a bargain compared to today’s launch prices. Even the inexpensive Falcon 9 is in the neighborhood of $3,000 per pound. If they can get Starship’s capacity up to 200 or 250 tons, then the bargain is so much greater, $250 or $200 per pound, respectively.

Starship currently has some customers. Superbird-9, a communication satellite that could launch in the summer of next year, and Starlab, a private space station that could launch in 2028.

At $100 million per launch, SpaceX could recover its development costs in about 100 customer flights. In the past, I have guessed a $20 million price tag, which would take 500 customer flights to recover development costs.

On the other hand, Starship could save SpaceX a large amount of money launching Starlink satellites, vs launching on Falcon 9, and it could recover the development costs in a few hundred Starlink launches without any external customers at all.

On the third hand, the gripping hand, Starship was conceived to build a colony on Mars, which means that SpaceX wanted it whether or not it could launch any customer payloads, and it was conceived before Starlink was conceived (which was intended to fund both Starship development and the Martian colony, and now could also fund additional goals that SpaceX is seriously considering), so the Mars mission was its only real mission at that time.

If SpaceX can get 250 tons per launch, then the number of tanker flights to re-tank the Mars and lunar versions of Starship would be greatly reduced. Several people have been rather upset that these interplanetary missions would require so many flights to refill Starship tanks. I think we were spoiled by NASA’s choice of Lunar Orbit Rendezvous for Apollo, because that did it all with one launch. Another option was Earth Orbit Rendezvous, in which several launches would each take one element of the Apollo mission into low Earth orbit for assembly/attachment. Once all the elements were put together, Apollo would launch to the Moon. This alternate concept is not so different than having a number of tanker flights for Starship.

This large number of tanker flights is also one reason why I think that Starship is not well suited for the Human Landing System for Artemis. It shows that it is too massive for the task. It will work, don’t get me wrong, but it is inefficient and other companies should be able to design better lunar landers, perhaps more along the lines of Blue Origin’s Blue Moon.

Richard M observed: “So many new players are pursuing methane rather than hydrogen for their first stages — it might be worth asking why that is.”

Because they are Fascist Capitalists that will destroy the Moon’s climate for profit. Methane is the new Carbon.

Edward,

Starship is not “too massive” or “inefficient” for the Moon. Other than the first one or two Artemis missions, future lunar Starship missions will carry maximum loads as SpaceX undertakes a phased industrialization of the Moon in pursuit of extraterrestrial construction of AI data centers to be based in cis-lunar space. Maximum loads will be normative for most future Starship missions, be they for Starlink deployment, Golden Dome deployment, tanker flights to refill orbiting depots or freight loads with lunar and Martian destinations.

Dick Eagleson,

Starship is designed for operations in Earth’s atmosphere at a fairly high acceleration. A version that would be constructed in space could have a thinner hull and perhaps fewer engines, Even without the thermal protection tiles, it is heavier than necessary for the mission of landing on the Moon, but the lunar Starship as it is being designed now must get itself into space from the Earth’s surface, making its hull as heavy as the other versions. A ship designed for lunar gravity and lower accelerations would certainly be lighter than one that must carry a full load of propellant on Earth and suffer a high G-load during launch from Earth, including a max-Q stress, because it need not have a heavy, thick hull. The current lunar Starship must do those, so its hull is thick and heavy.

A different design, perhaps without a nosecone, may be even lighter for cargo runs. Without travel through the atmosphere, the nosecone is unnecessary. Blue Origin’s Blue Moon is light weight, like this.

Starship was designed for trips to Mars. It is optimized for that. It is being repurposed for trips to the Moon, because that is what we will likely have soonest, and we seem to be in a stupid race to the Moon rather than planning and executing a long-term space economy.

SpaceX seems, now, to be thinking about a space economy, and it seems positioned to be a major leader in that economy. However, leaders have to make sure that they make good decisions, or they may end up like IBM did in the world of personal computers.