Germany’s space agency DLR delivers one prototype leg for Europe’s Callisto grasshopper

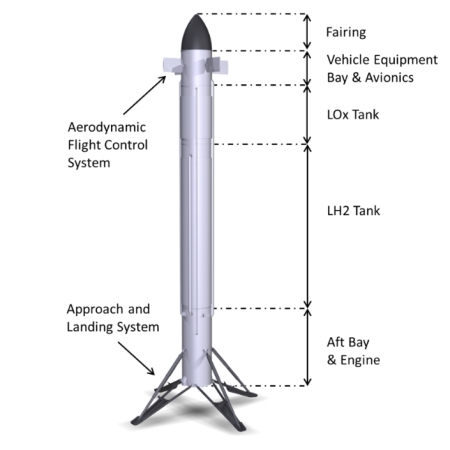

Callisto’s basic design

Government in-action: After a decade of work, the German space agency DLR this week finally delivered for testing a prototype leg of the Callisto grasshopper-type demo rocket, intended by the European Space Agency (ESA) to demonstrate vertical take-off and landing.

On 9 October, the Institute of Structures and Design announced that it had delivered a qualification model of the demonstrator’s landing leg to the Institute of Space Systems in Bremen. According to a 3 December 2024 update, the leg will now undergo a series of tests at the Institute’s Landing and Mobility Facility, including deployment, touchdown, and vibration testing.

Once the qualification test campaign is complete and the landing leg design has been validated, the Institute of Structures and Design will proceed with the construction of the four flight-ready legs.

Note again that Callisto, as shown to the right, was proposed as a joint ESA and JAXA project in 2015. Only now, a decade later, as DLR delivered one prototype leg. The first test hop has been repeatedly delayed, so that now it is now not expected to happen until 2027, and that rocket will not even be an operational version, it will simply be a small scale prototype.

Meanwhile, SpaceX has landed its Falcon 9 first stage hundreds of times, and reused them dozens of times. Other companies are flying or building their own reusable rockets, and hope to fly operational versions next year.

The contrast between this government project and the private sector is quite embarrassing. What makes it even more embarrassing is that it is par for the course, and yet so many people still look to the government as the god who can get things done. When will people learn?

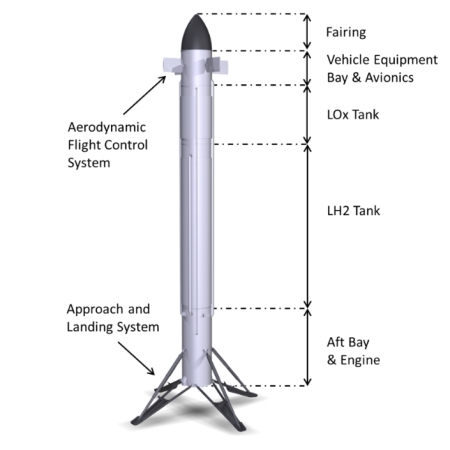

Callisto’s basic design

Government in-action: After a decade of work, the German space agency DLR this week finally delivered for testing a prototype leg of the Callisto grasshopper-type demo rocket, intended by the European Space Agency (ESA) to demonstrate vertical take-off and landing.

On 9 October, the Institute of Structures and Design announced that it had delivered a qualification model of the demonstrator’s landing leg to the Institute of Space Systems in Bremen. According to a 3 December 2024 update, the leg will now undergo a series of tests at the Institute’s Landing and Mobility Facility, including deployment, touchdown, and vibration testing.

Once the qualification test campaign is complete and the landing leg design has been validated, the Institute of Structures and Design will proceed with the construction of the four flight-ready legs.

Note again that Callisto, as shown to the right, was proposed as a joint ESA and JAXA project in 2015. Only now, a decade later, as DLR delivered one prototype leg. The first test hop has been repeatedly delayed, so that now it is now not expected to happen until 2027, and that rocket will not even be an operational version, it will simply be a small scale prototype.

Meanwhile, SpaceX has landed its Falcon 9 first stage hundreds of times, and reused them dozens of times. Other companies are flying or building their own reusable rockets, and hope to fly operational versions next year.

The contrast between this government project and the private sector is quite embarrassing. What makes it even more embarrassing is that it is par for the course, and yet so many people still look to the government as the god who can get things done. When will people learn?