Communications resume with Mars

Go here and here for the original images.

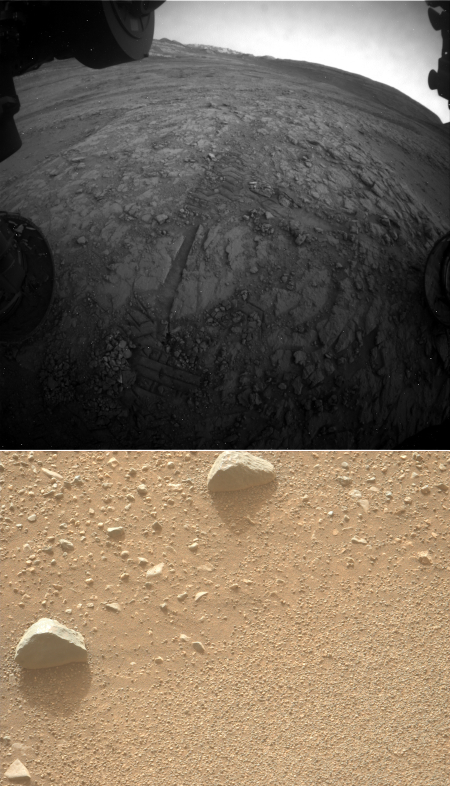

It appears the solar conjunction that has blocked all communications with the rovers and orbiters for the past three weeks around Mars has now fully ended, with the first new images appearing today from both Curiosity and Perseverance.

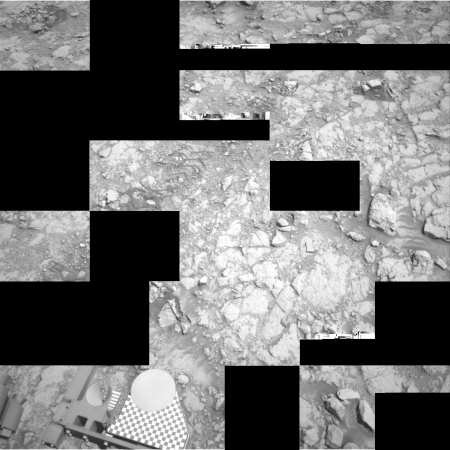

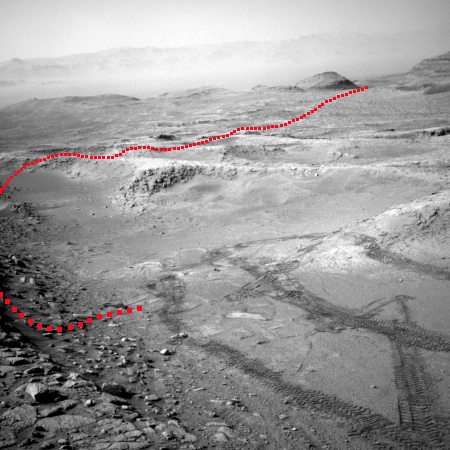

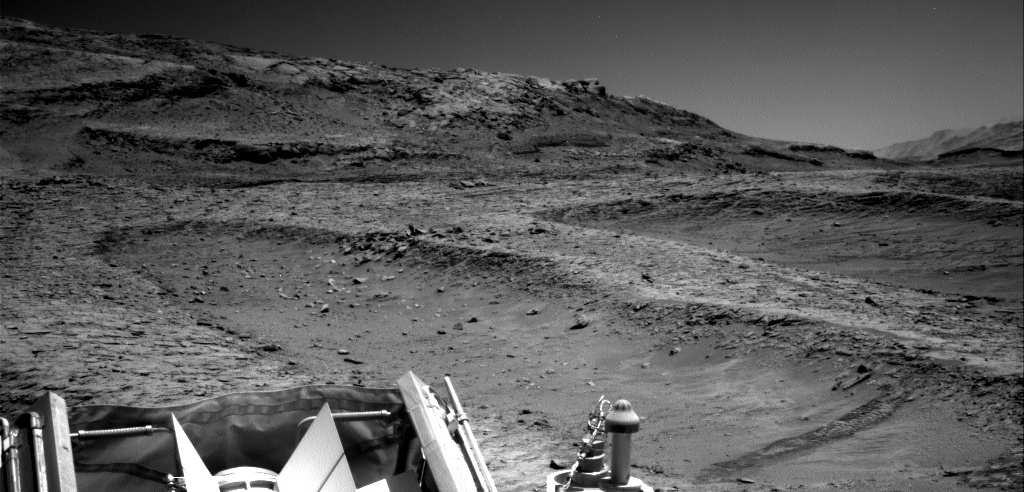

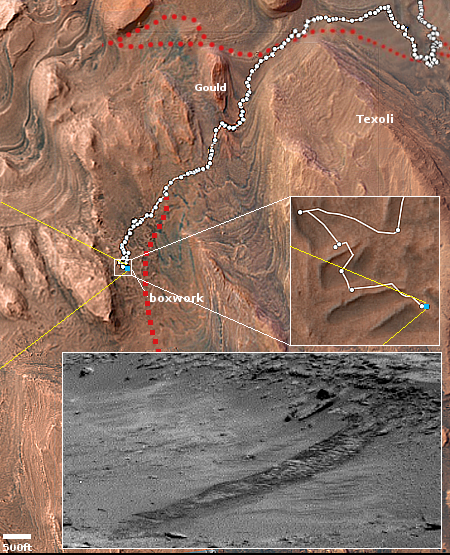

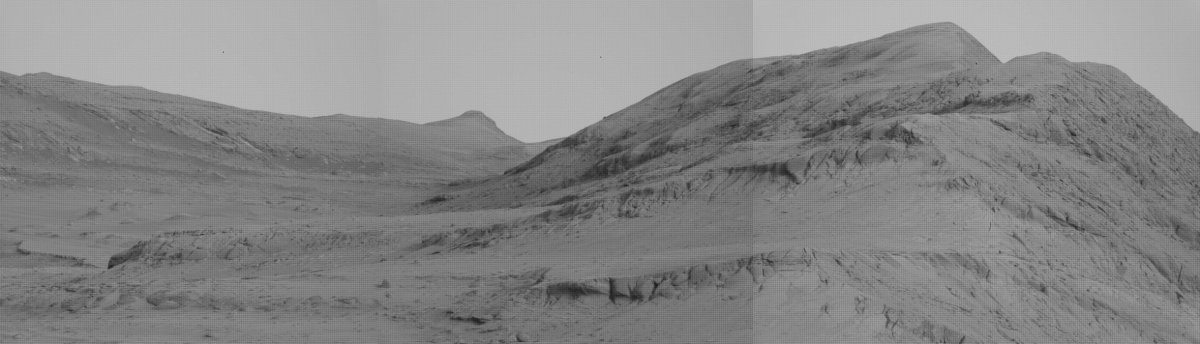

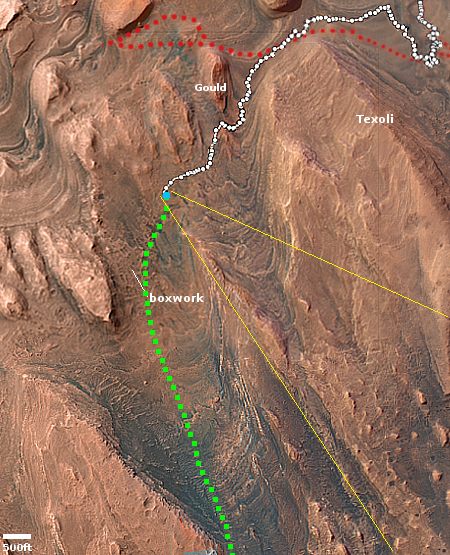

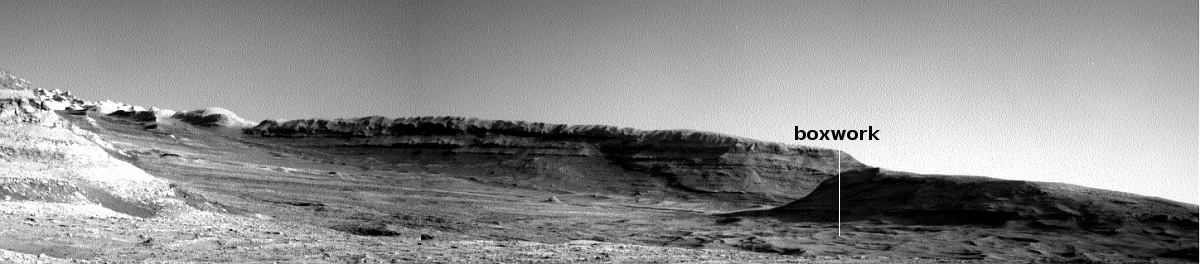

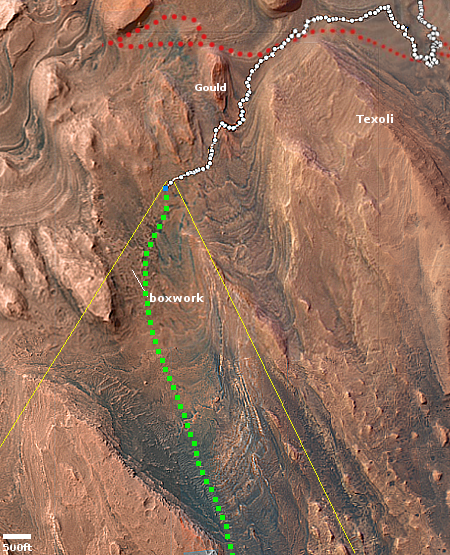

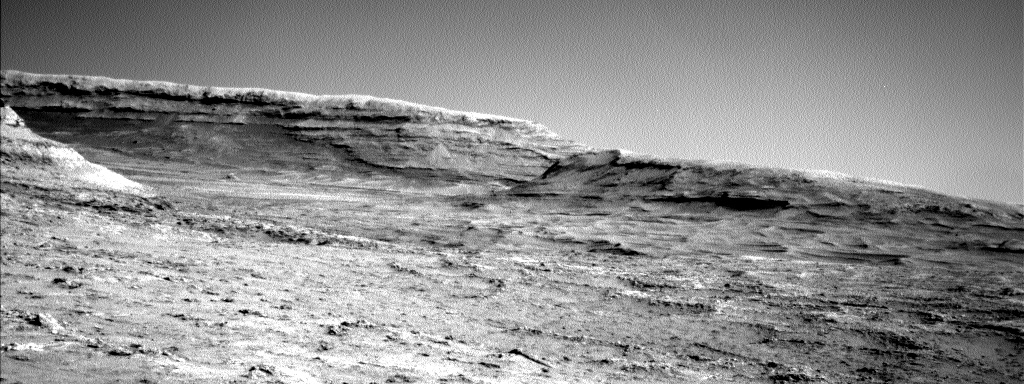

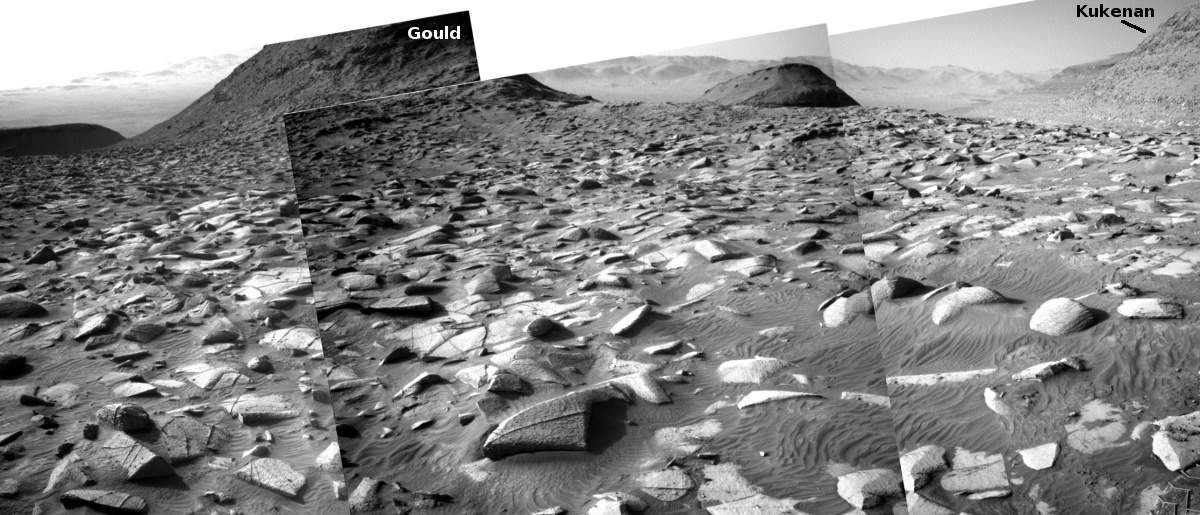

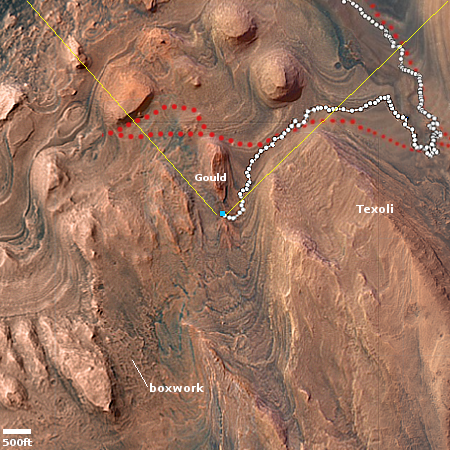

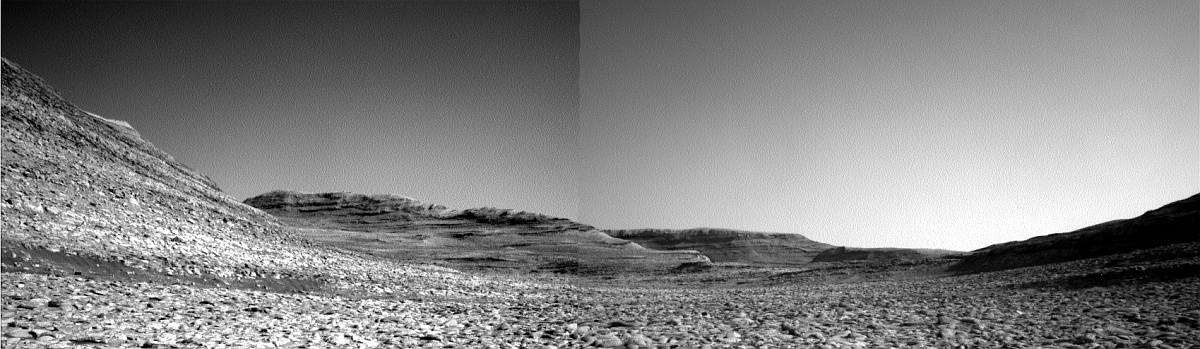

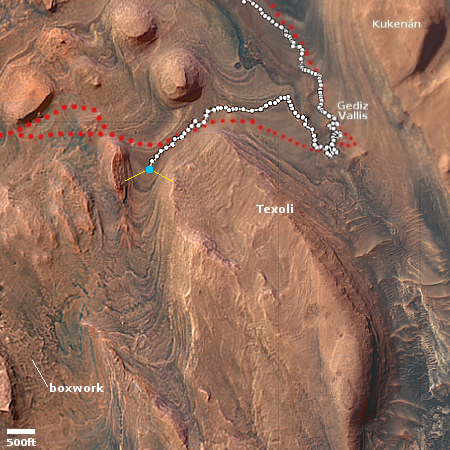

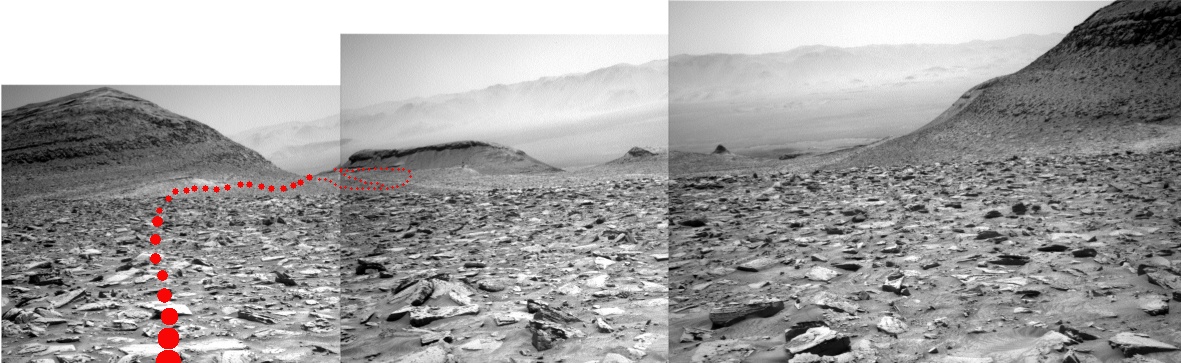

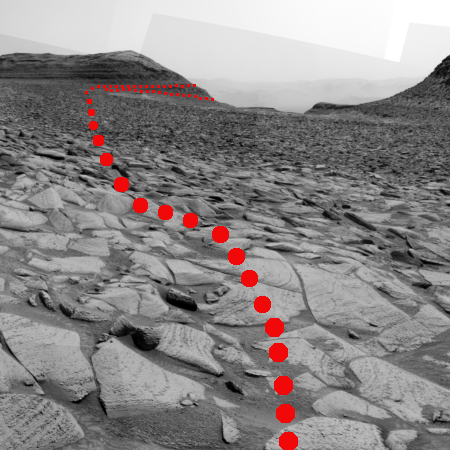

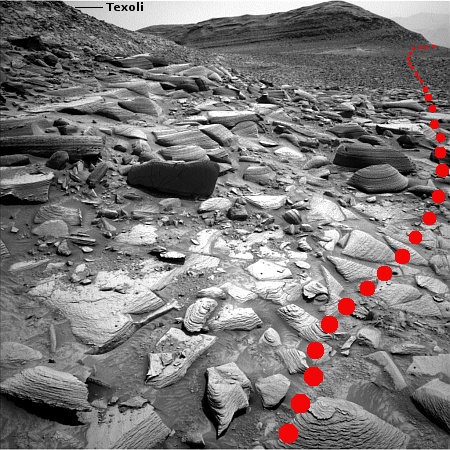

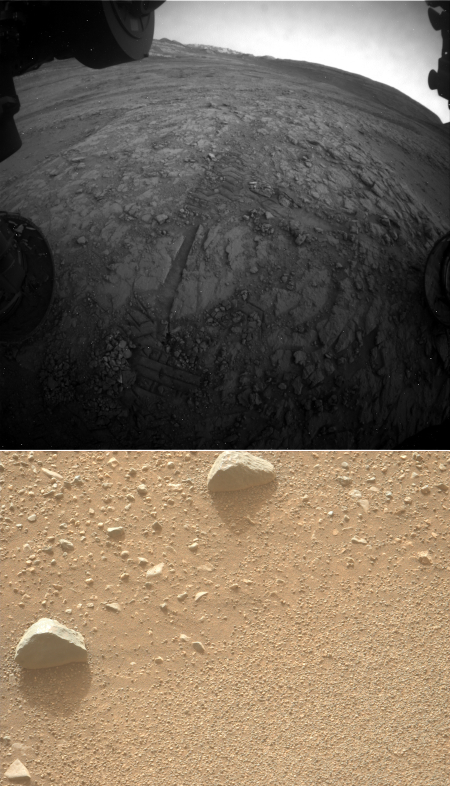

The two images to the right were downloaded today. The top image was taken on January 20, 2026 by Curiosity’s front hazard avoidance camera. It appears to be looking uphill in the direction the rover is soon to travel, climbing Mount Sharp. If you look closely you can see the mountain’s higher ranges on the horizon, just to the right of the rover itself.

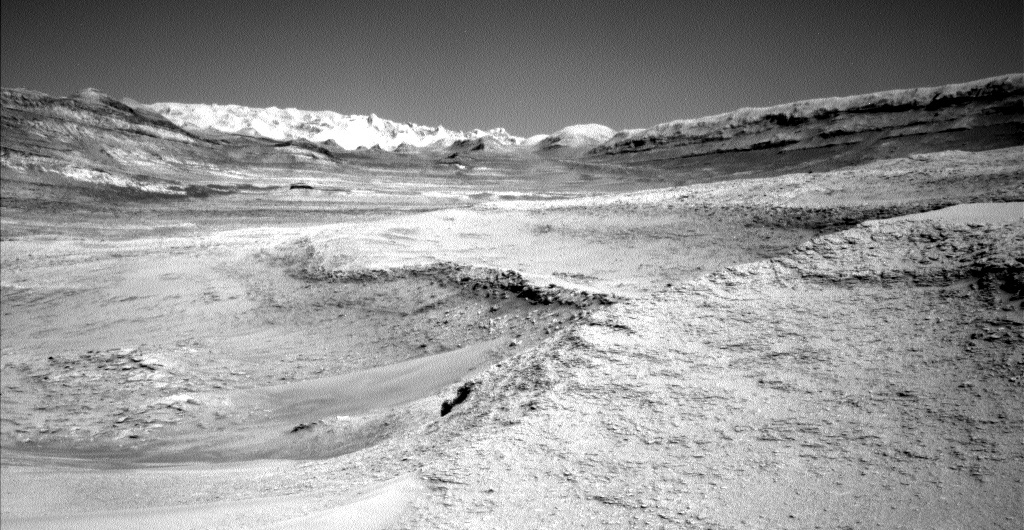

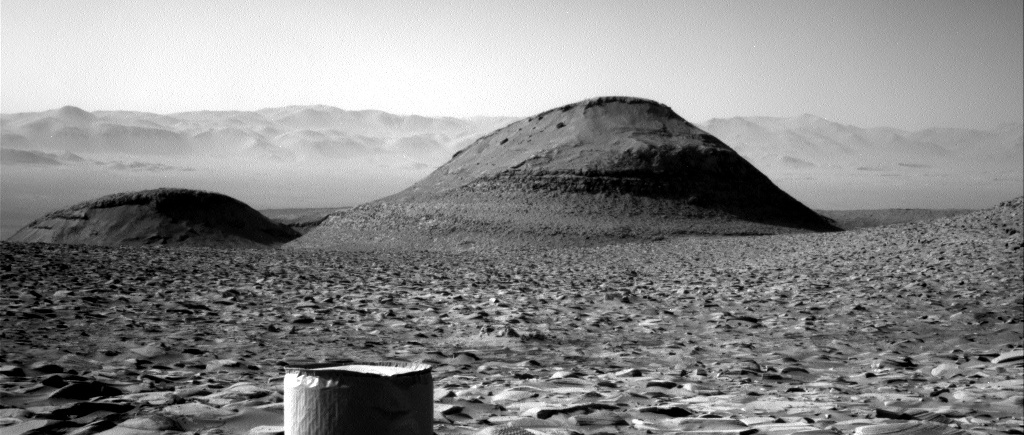

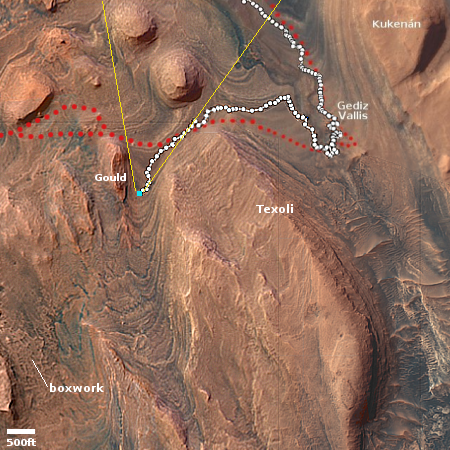

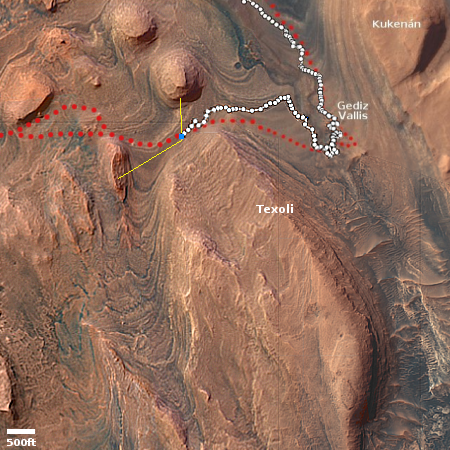

The bottom picture was actually taken on January 15, 2026 by Perseverance, but was only downloaded today. Both science teams had programmed their rovers to take images throughout the conjunction, scheduled for download when communications resumed.

The picture was taken by Perseverance’s left high resolution camera located on top of the rover’s mast. It looks down at the ground near the rover at the pebbles and rocks that strewn the relatively smooth surface of the terrain west of Jezero crater.

Neither image is particularly ground-breaking. What is important however is that both images prove the rovers are functioning as expected. Expect a lot more data to arrive in the next few days, all gathered during three weeks of blackout.

Go here and here for the original images.

It appears the solar conjunction that has blocked all communications with the rovers and orbiters for the past three weeks around Mars has now fully ended, with the first new images appearing today from both Curiosity and Perseverance.

The two images to the right were downloaded today. The top image was taken on January 20, 2026 by Curiosity’s front hazard avoidance camera. It appears to be looking uphill in the direction the rover is soon to travel, climbing Mount Sharp. If you look closely you can see the mountain’s higher ranges on the horizon, just to the right of the rover itself.

The bottom picture was actually taken on January 15, 2026 by Perseverance, but was only downloaded today. Both science teams had programmed their rovers to take images throughout the conjunction, scheduled for download when communications resumed.

The picture was taken by Perseverance’s left high resolution camera located on top of the rover’s mast. It looks down at the ground near the rover at the pebbles and rocks that strewn the relatively smooth surface of the terrain west of Jezero crater.

Neither image is particularly ground-breaking. What is important however is that both images prove the rovers are functioning as expected. Expect a lot more data to arrive in the next few days, all gathered during three weeks of blackout.