Just arrived at Glacier, where the internet access is bad, and there is no cell service. Thus, this might be my last post for the week. I will try to post in the evening, but this is a vacation, so it will not be my first priority. If I could do it in my room that would okay, but I have to go down to the lobby of the Lake McDonald Lodge.

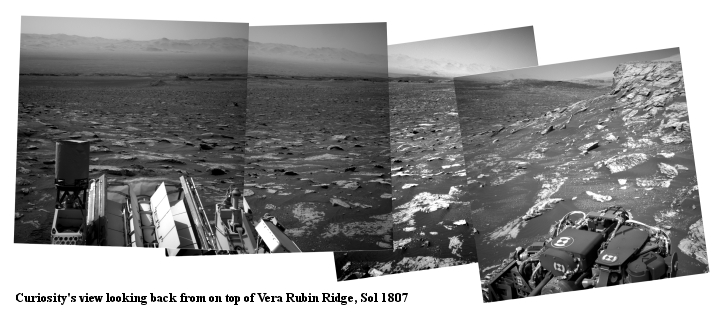

Anyway the image to the right was taken by me by holding my hand filter out at arm’s length, blocking the sun, and snapping a picture with my camera. It came out far better than I expected, as you can actually see the sun in the filter, partly blocked.

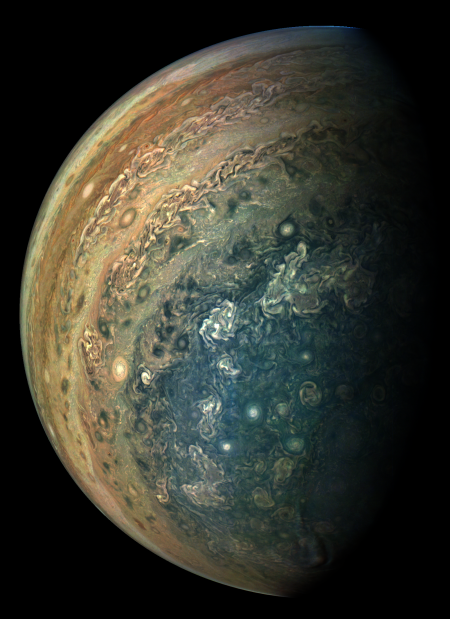

Totality was amazing. I was amazed by two things. First, how quiet it became. There were about hundred people scattered about the hotel lawn, with dogs and kids playing around. The hotel manager’s husband set up speakers for music and to make announcements, but when totality arrived he played nothing. People stopped talking. A hush fell over everything. Moreover, I think we somehow imagine a subconscious roar from the full sun. Covered as it was, with its soft corona gleaming gently around it, it suddenly seemed still.

Secondly, the amazing unlikeliness of the Moon being at just the right distance and size to periodically cause this event seemed almost miraculous. Watching it happen drove this point home to me. And since eclipses themselves have been a critical event in the intellectual development of humanity, helping to drive learning and our understanding of the universe, it truly makes me wonder at the majesty of it. I do not believe in any particular religion or their rituals (though I consider the Bible, the Old Testament especially, to be a very good manual for creating a good life and society), but I do not deny the existence of a higher power. Something made this place, and set it up in this wonderous way. Today’s eclipse only served to demonstrate this fact to me again.

Posting will be light for the rest of the week. If I get a chance I will add some more pictures to this post tomorrow.

» Read more