Is a supermassive black hole is hidden in the Large Magellanic Cloud?

Based on the motions of a number of runaway stars on the edge of the Milky Way that are moving so fast they will leave the galaxy, astronomers believe that many were accelerated not by the galaxy’s own central supermassive black hole but a previously undetected supermassive black hole at the center of the Large Magellanic Cloud, one of the Milky Ways nearby dwarf galaxies.

To make this discovery, researchers traced the paths with ultra-fine precision of 21 stars on the outskirts of the Milky Way. These stars are traveling so fast that they will escape the gravitational clutches of the Milky Way or any nearby galaxy. Astronomers refer to these as “hypervelocity” stars.

Similar to how forensic experts recreate the origin of a bullet based on its trajectory, researchers determined where these hypervelocity stars come from. They found that about half are linked to the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. However, the other half originated from somewhere else: a previously-unknown giant black hole in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC).

You can read the paper here [pdf]. This result was made possible by the very precise location and velocity data of over a billion stars measured by Europe’s Gaia satellite.

Based on the available data, the scientists estimate (with great uncertainty) the mass of this supermassive black hole, which the scientists have dubbed LMC* (pronounced “LMC star”), to be about 600,000 times the mass of the Sun, quite big but significantly less than the mass of the Milky Way’s central black hole, Sagittarius A* (pronounced “A-star”), which is estimated to be about 4.3 million times the mass of the Sun.

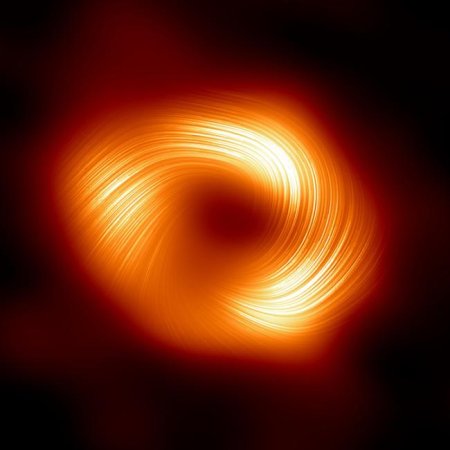

The mystery to solve now is why this super massive black hole is so quiet. It has literally emitted no obvious energy in any wavelength in the past seven decades, since ground- and space-based telescopes went into operation capable of detecting such emissions. Even the relatively inactive supermassive black hole at the Milky Way’s center, Sagittarius A* (pronounced “A-star”) emits distinct radio energy that the first radio telescopes were able to detect almost immediately.

Based on the motions of a number of runaway stars on the edge of the Milky Way that are moving so fast they will leave the galaxy, astronomers believe that many were accelerated not by the galaxy’s own central supermassive black hole but a previously undetected supermassive black hole at the center of the Large Magellanic Cloud, one of the Milky Ways nearby dwarf galaxies.

To make this discovery, researchers traced the paths with ultra-fine precision of 21 stars on the outskirts of the Milky Way. These stars are traveling so fast that they will escape the gravitational clutches of the Milky Way or any nearby galaxy. Astronomers refer to these as “hypervelocity” stars.

Similar to how forensic experts recreate the origin of a bullet based on its trajectory, researchers determined where these hypervelocity stars come from. They found that about half are linked to the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. However, the other half originated from somewhere else: a previously-unknown giant black hole in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC).

You can read the paper here [pdf]. This result was made possible by the very precise location and velocity data of over a billion stars measured by Europe’s Gaia satellite.

Based on the available data, the scientists estimate (with great uncertainty) the mass of this supermassive black hole, which the scientists have dubbed LMC* (pronounced “LMC star”), to be about 600,000 times the mass of the Sun, quite big but significantly less than the mass of the Milky Way’s central black hole, Sagittarius A* (pronounced “A-star”), which is estimated to be about 4.3 million times the mass of the Sun.

The mystery to solve now is why this super massive black hole is so quiet. It has literally emitted no obvious energy in any wavelength in the past seven decades, since ground- and space-based telescopes went into operation capable of detecting such emissions. Even the relatively inactive supermassive black hole at the Milky Way’s center, Sagittarius A* (pronounced “A-star”) emits distinct radio energy that the first radio telescopes were able to detect almost immediately.