Six of the ten cubesats launched toward the Moon by SLS still working

Of the ten cubesats launched toward the Moon by SLS last week, six are still working while four have problems that are likely killing their missions.

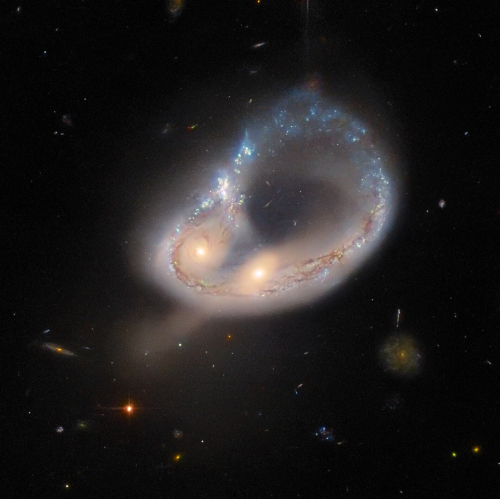

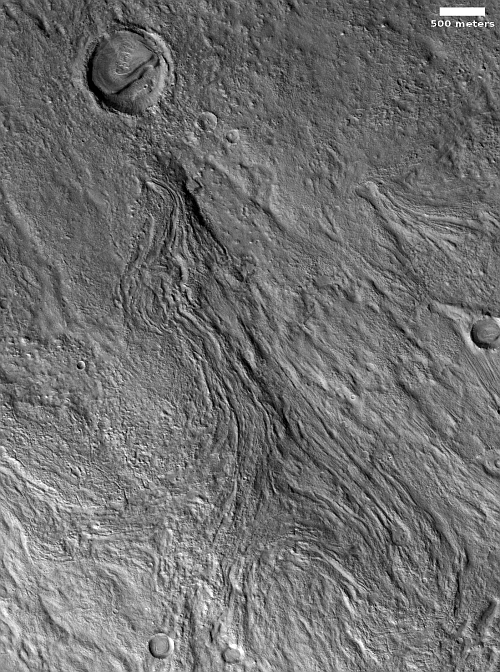

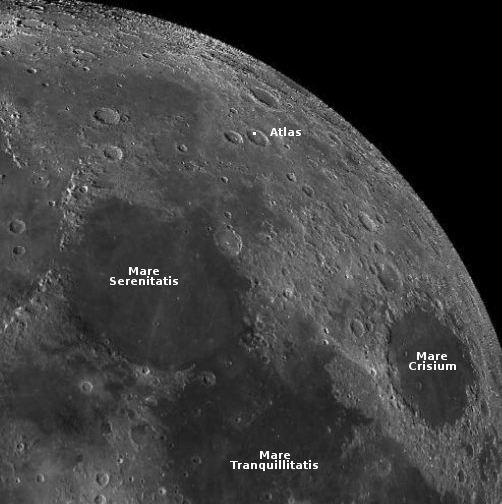

The photo to the right, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was taken by ArgoMoon, an Italian cubesat that is working perfectly. The large impact basin visible is Orientale Basin, located just on the edge of the visible face of the Moon but partly hidden on the far side.

A summary of the status of all ten can be found here. Of the other five still functioning properly, all have been able to maintain proper communications.

Possibly the biggest disappointment however is the failure of Japan’s Omotenashi lander, which was going to attempt a lunar soft landing. Shortly after launch it began tumbling, and engineers were never able to regain full control or communications. The landing attempt has now been abandoned.

Side note: Orion itself also captured some images as it zipped past the Moon yesterday, but they do not appear as high quality as ArgoMoon’s pictures.

Of the ten cubesats launched toward the Moon by SLS last week, six are still working while four have problems that are likely killing their missions.

The photo to the right, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was taken by ArgoMoon, an Italian cubesat that is working perfectly. The large impact basin visible is Orientale Basin, located just on the edge of the visible face of the Moon but partly hidden on the far side.

A summary of the status of all ten can be found here. Of the other five still functioning properly, all have been able to maintain proper communications.

Possibly the biggest disappointment however is the failure of Japan’s Omotenashi lander, which was going to attempt a lunar soft landing. Shortly after launch it began tumbling, and engineers were never able to regain full control or communications. The landing attempt has now been abandoned.

Side note: Orion itself also captured some images as it zipped past the Moon yesterday, but they do not appear as high quality as ArgoMoon’s pictures.