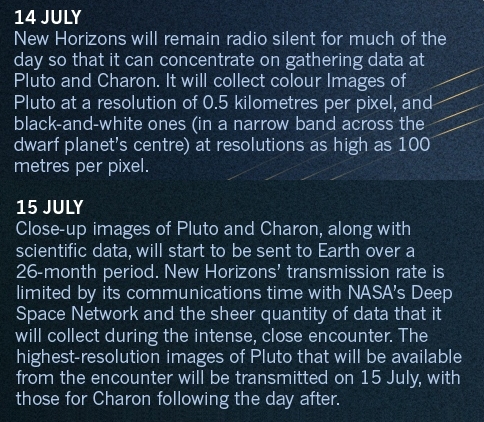

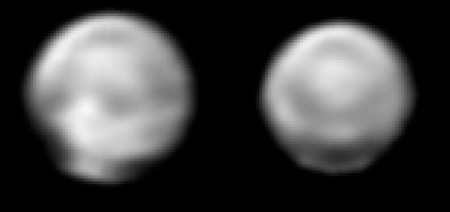

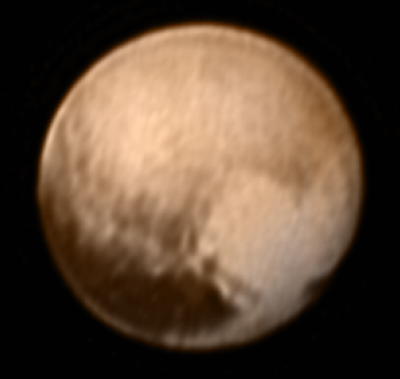

Best image yet of Pluto

Very cool image time! The New Horizons science team today released [link fixed] their best image yet of Pluto, taken on July 7 immediately following the spacecraft’s recovery from safe mode.

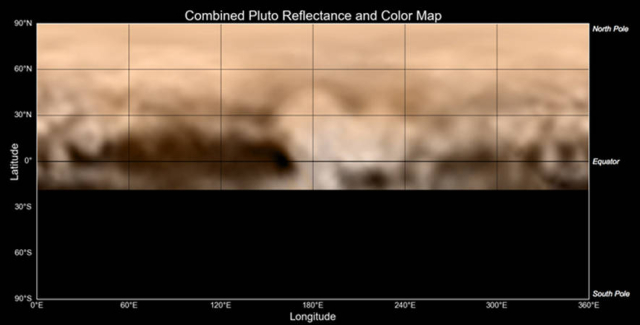

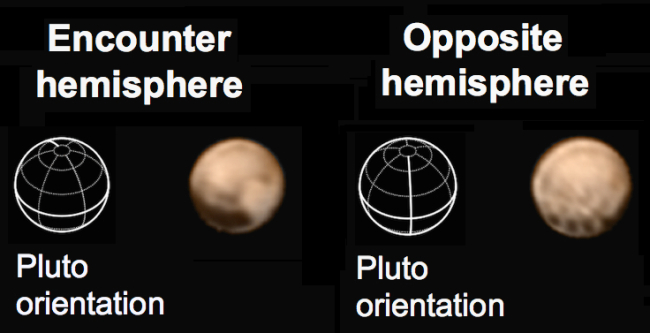

This view is centered roughly on the area that will be seen close-up during New Horizons’ July 14 closest approach. This side of Pluto is dominated by three broad regions of varying brightness. Most prominent are an elongated dark feature at the equator, informally known as “the whale,” and a large heart-shaped bright area measuring some 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers) across on the right. Above those features is a polar region that is intermediate in brightness.

For the first time these features look like actual surface areas on a planet, not fuzzy blobs. We are still seeing Pluto like we saw all planets prior to the space age, but at least now we know what we are looking at.

Very cool image time! The New Horizons science team today released [link fixed] their best image yet of Pluto, taken on July 7 immediately following the spacecraft’s recovery from safe mode.

This view is centered roughly on the area that will be seen close-up during New Horizons’ July 14 closest approach. This side of Pluto is dominated by three broad regions of varying brightness. Most prominent are an elongated dark feature at the equator, informally known as “the whale,” and a large heart-shaped bright area measuring some 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers) across on the right. Above those features is a polar region that is intermediate in brightness.

For the first time these features look like actual surface areas on a planet, not fuzzy blobs. We are still seeing Pluto like we saw all planets prior to the space age, but at least now we know what we are looking at.