First exoplanet detected in another galaxy?

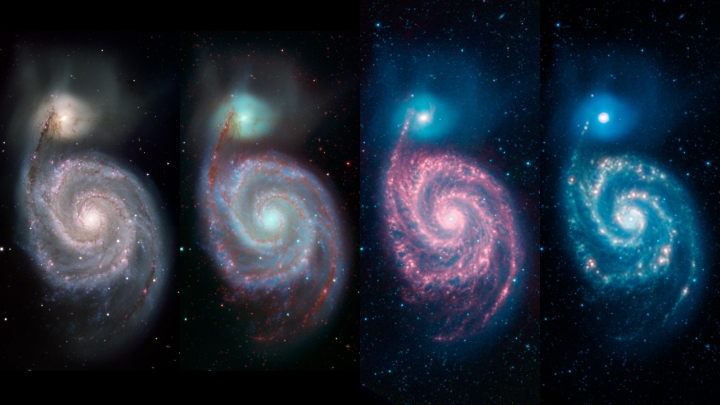

The uncertainty of science: Using the Chandra X-ray Observatory, astronomers think they may have detected the first exoplanet ever found in another galaxy, the Whirlpool Galaxy, 28 million light years away.

This new result is based on transits, events in which the passage of a planet in front of a star blocks some of the star’s light and produces a characteristic dip. Astronomers using both ground-based and space-based telescopes — like those on NASA’s Kepler and TESS missions — have searched for dips in optical light, electromagnetic radiation humans can see, enabling the discovery of thousands of planets.

Di Stefano and colleagues have instead searched for dips in the brightness of X-rays received from X-ray bright binaries. These luminous systems typically contain a neutron star or black hole pulling in gas from a closely orbiting companion star. The material near the neutron star or black hole becomes superheated and glows in X-rays.

Because the region producing bright X-rays is small, a planet passing in front of it could block most or all of the X-rays, making the transit easier to spot because the X-rays can completely disappear. This could allow exoplanets to be detected at much greater distances than current optical light transit studies, which must be able to detect tiny decreases in light because the planet only blocks a tiny fraction of the star.

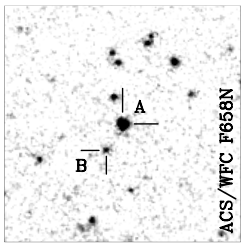

The team used this method to detect the exoplanet candidate in a binary system called M51-ULS-1, located in M51. This binary system contains a black hole or neutron star orbiting a companion star with a mass about 20 times that of the Sun. The X-ray transit they found using Chandra data lasted about three hours, during which the X-ray emission decreased to zero. Based on this and other information, the researchers estimate the exoplanet candidate in M51-ULS-1 would be roughly the size of Saturn, and orbit the neutron star or black hole at about twice the distance of Saturn from the Sun.

While this is a tantalizing study, more data would be needed to verify the interpretation as an extragalactic exoplanet. One challenge is that the planet candidate’s large orbit means it would not cross in front of its binary partner again for about 70 years, thwarting any attempts for a confirming observation for decades. [emphasis mine]

As the press release says, this data is tantalizing, but it is really insufficient to prove that an exoplanet has been found. What is known is that for some reason the X-ray emissions from the X-ray binary system disappeared for about three hours. An exoplanet could be one explanation. So could many other things.

The uncertainty of science: Using the Chandra X-ray Observatory, astronomers think they may have detected the first exoplanet ever found in another galaxy, the Whirlpool Galaxy, 28 million light years away.

This new result is based on transits, events in which the passage of a planet in front of a star blocks some of the star’s light and produces a characteristic dip. Astronomers using both ground-based and space-based telescopes — like those on NASA’s Kepler and TESS missions — have searched for dips in optical light, electromagnetic radiation humans can see, enabling the discovery of thousands of planets.

Di Stefano and colleagues have instead searched for dips in the brightness of X-rays received from X-ray bright binaries. These luminous systems typically contain a neutron star or black hole pulling in gas from a closely orbiting companion star. The material near the neutron star or black hole becomes superheated and glows in X-rays.

Because the region producing bright X-rays is small, a planet passing in front of it could block most or all of the X-rays, making the transit easier to spot because the X-rays can completely disappear. This could allow exoplanets to be detected at much greater distances than current optical light transit studies, which must be able to detect tiny decreases in light because the planet only blocks a tiny fraction of the star.

The team used this method to detect the exoplanet candidate in a binary system called M51-ULS-1, located in M51. This binary system contains a black hole or neutron star orbiting a companion star with a mass about 20 times that of the Sun. The X-ray transit they found using Chandra data lasted about three hours, during which the X-ray emission decreased to zero. Based on this and other information, the researchers estimate the exoplanet candidate in M51-ULS-1 would be roughly the size of Saturn, and orbit the neutron star or black hole at about twice the distance of Saturn from the Sun.

While this is a tantalizing study, more data would be needed to verify the interpretation as an extragalactic exoplanet. One challenge is that the planet candidate’s large orbit means it would not cross in front of its binary partner again for about 70 years, thwarting any attempts for a confirming observation for decades. [emphasis mine]

As the press release says, this data is tantalizing, but it is really insufficient to prove that an exoplanet has been found. What is known is that for some reason the X-ray emissions from the X-ray binary system disappeared for about three hours. An exoplanet could be one explanation. So could many other things.