Anna Weatherup – Be Thou My Vision

An evening pause: It all depends on how you define God. To me, God is the entire universe, of which I am part. To recognize such a reality is terribly humbling, and leads to wisdom.

An evening pause: It all depends on how you define God. To me, God is the entire universe, of which I am part. To recognize such a reality is terribly humbling, and leads to wisdom.

Capitalism in space: Using the robot arm on ISS, astronauts on December 21st installed Nanoracks’ commercial airlock, dubbed Bishop, in its place on the station.

I think this is the second private module installed on ISS, following Bigelow’s inflatable BEAM module. Bishop is for equipment only, and supplements the equipment airlock on the Japanese Kibo module. It is also five times larger, and rather than use hatches, it deploys equipment outside of ISS using the robot arm. Each time Nanoracks wants to use it to deploy a commercial cubesat they will use the arm to unberth Bishop, deploy the satellite through the docking port, and then re-berth it.

Bishop and BEAM are harbingers of the future on ISS. Axiom will be adding its own private modules in ’24. And then there are the upcoming private tourist flights. Both Axiom (using Dragon) and Russia (using Soyuz) have such flights scheduled before the end of ’21.

Assuming the economy doesn’t crash due to government oppression and mismanagement, gradually over the next decade expect operations on ISS and future stations to shift from the government to commercial private operations, aimed at making profits instead of spending taxpayer money.

NASA today revealed that engineers were forced on December 20th to abort at about T-5 minutes their second attempt to do a fueled dress rehearsal countdown in preparation for the full core stage static fire test.

[S]ources said the terminal countdown started at T-10 minutes and counting and ran down to T-4 minutes and 40 seconds where an unplanned hold occurred. … The criteria for how long it should take for a liquid hydrogen replenish valve to close was violated at that point in the countdown when the valve was commanded to the close position as a part of the process to pressurize the liquid hydrogen tank for engine firing. After holding at the T-4:40 point for a few minutes, teams decided the terminal countdown test couldn’t continue.

Vehicle safing and recycle sequences were then executed.

Although the countdown ran for over half of its intended duration, the early cutoff left several major milestones untested. With the countdown aborted at that point, the stage’s propellant tanks weren’t fully pressurized, the hydraulic Core Stage Auxiliary Power Units (CAPUs) were never started, the final RS-25 engine purge sequence was never run, and the vehicle power transfer didn’t occur.

NASA management is debating now whether they can proceed directly to the full core stage static fire test, where the core stage engine will fire for the full duration of a normal launch. It could be that they will decide to waive testing what was not tested on this last dress rehearsal.

If they delay the full test to do another dress rehearsal, they risk causing a delay in the fall launch of SLS, as they need a lot of time to disassemble, ship, and reassembly the stage in Florida. If they don’t delay, they risk either a failure during the full static fire test, or (even worse) a failure during that first launch.

Considering the number of nagging problems that have plagued this test program, it seems foolish to me to bypass any testing. They not only do not have enough data to really understand how to fuel the core stage reliably, they don’t even have a lot of practice doing the countdown itself. All this bodes ill when they try to launch later this year, especially if they decide to not work the kinks out now.

Capitalism in space: Axiom, the company building the next private modules to be added to ISS, has chosen Houston as the location for its astronaut training and space station construction facility.

Axiom Space, based in Houston, plans to develop a 14-acre headquarters campus at the spaceport located at Ellington Airport. It will use this campus to train private astronauts and for production of its Axiom Station. Mayor Sylvester Turner announced the project on Tuesday.

…Terms of the deal, including how the development would be financed, are still being worked out and must be approved by City Council. The Houston Airport System, for instance, could help provide financing that Axiom Space would pay back.

Axiom said construction could begin in 2021, and it expects to have a functional headquarters campus in 2023. The company grew its workforce to 90 people this year and is looking to hire another 100 next year. Ultimately, it could add more than 1,000 jobs for the Houston area.

For Axiom, the most important event in the coming year will be its private manned mission to ISS, using SpaceX’s Dragon capsule. That flight, presently scheduled for the fall, will put it on the map.

Capitalism in space: Less than two weeks after Starship prototype #9 had fallen off its stand and hit the side of the assembly building, damaging its fins and hull, SpaceX has repaired the damage and moved the prototype to the launchpad in preparation for its test flight, expected sometime in the next three weeks.

The pace that SpaceX operates continues to astound, though in truth it is the right pace. If more American companies (as well as Americans) emulated it, many of the problems the country now faces would vanish.

An evening pause: Feel the joy and good will. We should all feel this way, all the time.

Hat tip Cotour.

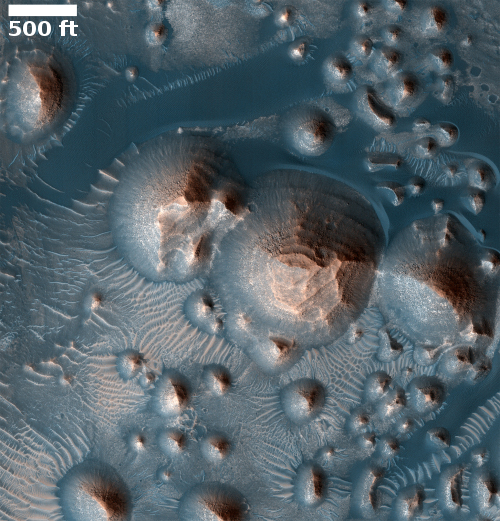

Cool image time! The photo to the right, rotated, cropped, and reduced to post here, was taken on September 30, 2020 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

It shows one half of what scientists have dubbed a pollywog crater, in which there is a single breach in the crater wall, aligned with the low point in the crater’s floor. Such craters suggest that they were once water- or ice-filled, and that they drained out through the breach either quickly in a single event or slowly over multiple events.

The second image below was taken by the wide angle context camera on MRO, and not only shows this entire crater, but several other adjacent craters, all of which show evidence of glacial fill in their interiors. The latitude here is 34 degrees south, placing these craters within the mid-latitude bands where such glacial features have been found by scientists in great numbers.

» Read more

The Arizona Republican Party yesterday announced that in response to the refusal by the Maricopa County election board to obey subpoenas that “the state’s GOP electors will intervene in the case.”

The reason I have put a question mark in the headline is that I really have no idea what this means, or if it is simply another example of failure theater by the Republican Party. Who are these electors? Are they the legislators? Are they the alternative slate of Trump electors chosen by legislature? What power do they have? How is this actrion going to do anything to get those subpoenas obeyed and a real audit of the election in Maricopa County accomplished?

Based on the story at the link, I have no idea, and instead have the impression that it is all for show, and will accomplish nothing. Moreover, for unelected bureaucrats to defy an order by the elected legislature is blatantly unconstitutional, and should have prompted immediate action by law enforcement to secure the audit machines, the ballots, and any evidence. None of this has happened, which suggests to me that our elected officials here in Arizona are impotent and powerless and rule only at the whim of those unelected bureaucrats.

After reviewing the available evidence the chairman of the Georgia state senate’s judiciary committee has issued a report calling the election results “untrustworthy” and demanding that the election certification be rescinded.

You can read the report here [pdf] The article at the link above provides a nice summary.

Georgia State Senator William T. Ligon, Chairman of the Election Law subcommittee, reached that conclusion after reviewing the recount process, the audit process, current investigations taking place, and litigation that is moving forward. His Subcommittee also heard testimonies from witnesses during an open hearing at the Georgia State Capitol on Thursday, December 3, 2020.

“The November 3, 2020 General Election (the “Election”) was chaotic and any reported results must be viewed as untrustworthy,” Sen. Ligon wrote in his executive summary.

The report itself lists in detail all the documented allegations, either from witness affidavits or testimony or from actual videos showing corruption, misbehavior, or very suspicious behavior. It is important to note that we are not talking about one or two allegations by only a few witnesses. We are talking of a giant stack, in the hundreds, many backed up by video evidence.

It does appear possible, from statements in the article above, that the Georgia state legislature might act to reject the certification and the chosen Democratic electors before January 6th.

Watch this December 18th statement by the elected sheriff of Bernalillo County, the most populous county in New Mexico that covers Albuquerque. He states unequivocally that his officers will not enforce the draconian edicts of his governor and local authorities. They will instead focus on “apprehending actual criminals.” He also added quite forcefully, “We will not follow along with any order that subverts [the public’s] constitutional rights.”

We need more sheriffs like him. These unlawful and unconstitutional edicts must end, and the best way to do that is for everyone to tell the petty dictators who are issuing them that we will no longer comply. This sheriff demonstrates how.

It only takes a little courage. I applaud this man for showing that he has that courage.

During the three-plus months in the summer when Curiosity stayed at one location for its most recent drilling campaign, the science team used its ChemCam Remote Micro-Imager camera (RMI), originally designed to take very close-up photos, to create a 216 photo mosaic of the long distance horizon. They have now released that mosaic, which you can see as a video at the link. The mosaic itself is a very long strip, which is best viewed up close and scrolling across it, as the video does. As the scientists note,

During Curiosity’s first year on Mars, it was recognized that, thanks to its powerful optics, RMI could also go from a microscope to a telescope and play a significant role as a long-distance reconnaissance tool. It gives a typical circular “spyglass” black and white picture of a small region. So RMI complements other cameras quite nicely, thanks to its very long focal length. When stitched together, RMI mosaics reveal details of the landscape several kilometers from the rover, and provides pictures that are very complementary to orbital observations, giving a more human-like, ground-based perspective.

From July to October of 2020, Curiosity stayed parked at the same place to perform various rock sampling analyses. This rare opportunity of staying at the same location for a long time was used by the team to target very distant areas of interest, building an ever-growing RMI mosaic between September 9 and October 23 (sols 2878 and 2921) that eventually became 216 overlapping images. When stitched into a 46947×7260 pixel panorama, it covers over 50 degrees of azimuth along the horizon, from the bottom layers of “Mount Sharp” on the right to the edge of “Vera Rubin Ridge” on the left.

The camera’s resolution is so good that it was able in the mosaic to resolve large boulders on the crater wall of Gale Crater almost 37 miles away.

With Jupiter and Saturn closer to each other in the sky than they have been in about 800 years, the science team for Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) decided to aim that lunar orbiter at the two gas giants to get a picture.

The photo to the right, cropped and expanded to post here, was also enhanced by the science team to brighten Saturn so that it would match Jupiter. As they note at the link,

[LRO] captured this view just a few hours after the point of closest separation (0.1°) between the two giant planets. With the sharp focus of the NAC [camera], you can see that the two planets are actually separated by about 10 Jupiter diameters

Both planets however look fuzzy in the image, probably because the camera was not designed to obtain sharp images from this distance. Nonetheless, this is a very cool photo.

No surprise: The NASA budget that was passed by Congress this week as part of a giant omnibus bill only gave NASA 25% of the requested funds the agency says it needs to develop a human lander required for an Artemis manned mission to the Moon by ’24.

Overall, NASA will receive $23.271 billion, almost $2 billion less than requested. Importantly for the Trump Administration’s Artemis program to return astronauts to the Moon by 2024, it provides only $850 million instead of $3.4 billion for Human Landing Systems.

…The Trump Administration requested a 12 percent increase for NASA in order to fund the Artemis program: $25.2 billion for FY2021 compared to the $22.9 billion it received in FY2020. While the goal of returning astronauts to the Moon has broad bipartisan support in Congress, the Trump deadline of 2024 — set because it would have been the end of his second term if he had been reelected — won lukewarm support at best from Republicans and none from Democrats who pointed to both budgetary and technical hurdles.

It was always clear that the Democrats were not going to cooperate with Trump to could get that lunar landing during his second term. Moreover, the real goal of Artemis is not space exploration, but distributing pork. Stretching out these missions so that they take many many years achieves that goal far better than a tight competitive schedule that gets things done. This is why SLS and Orion have been under construction, with no flights, for decades, even as SpaceX moves forward with Starship/Super Heavy in only a few years.

A Biden presidency actually increases the changes that Artemis will get better funding, but that funding will always be designed to stretch out the program for as long as possible. Our policymakers in Washington really do not care much for the interest of the nation. What they care about is their own power and aggrandizement.

The new colonial movement: Chinese engineers have decided to extend the mission of the Chang’e-5 lunar orbiter by shifting its orbit so that it is transferred to one of the five Sun-Earth Lagrange points.

Amateur radio operators first confirmed the Chang’e-5 orbiter was still in space and heading towards the moon. Official confirmation has now been provided as to the spacecraft’s status.

Hu Hao, a chief designer of the third (sample return) phase of the Chinese lunar exploration program, told China Central Television (Chinese) Dec. 20 that the orbiter is now on an extended mission to a Sun-Earth Lagrange point. Hu said the extended mission was made possible by the accurate orbital injection by the Long March 5 launch vehicle, the same rocket which failed in July 2017 and delayed Chang’e-5 by three years. The Chang’e-5 orbiter has more than 200 kilograms of propellant remaining for further maneuvers.

While unspecified, it is believed that the Chang’e-5 orbiter will enter orbit around L1, based on the reference to planned solar observations. The orbiter is equipped with optical imagers. The team will decide on a further destination after tests and observations have been conducted, Hu said.

It makes great sense to keep the orbiter operating, and since lunar orbits tend to be unstable, going to a Lagrange point makes even more sense.

However, this decision raises an interesting point for the future. There are only five Lagrange points in the Earth-Sun system. All have great value. All also can likely sustain a limited number of satellites and spacecraft. Who coordinates their operations? What happens if China fills each with its spacecraft? For example, the James Webb Space Telescope is aiming for Lagrange point #2, a million miles from Earth in the Earth’s shadow. While Chang’e-5 is presently heading to a different point, what happens if China changes its mind and puts Chang’e-5 in Webb’s way?

As far as I know, there has been no discussion of this issue in international circles.

The new colonial movement: Dmitri Rogozin, head of Russia’s Roscosmos space agency, announced this past weekend the recovery of the first stage and boosters from a December 18th Vostochny launch that, because of the polar orbit of the satellite, were dropped on Russian territory.

On Friday, a Soyuz 2.1b rocket launched from the Vostochny Cosmodrome, carrying its payload of 36 OneWeb satellites into space. Although Russia’s newest spaceport is located in the far eastern part of the country, it still lies several hundred kilometers from the Pacific Ocean.

This means that as Soyuz rockets climb into space from this location, they drop their stages onto the sparsely populated Yakutia region below. With the Soyuz rocket, there are four boosters that serve as the rocket’s “first stage,” and these drop away about two minutes after liftoff. Then, the “Blok A” second stage drops away later in the flight.

Although the Yakutia region is geographically rugged and sparsely populated, the Russian government does a reasonably good job of establishing drop zones for these stages and keeping them away from residential areas. This is what happened, as usual, with Friday’s launch. [emphasis mine]

The focus of the article at the link is the silly jabs at SpaceX that Rogozin included in his announcement. The real story, however, is that the Russian government, in deciding to build a new spaceport in Vostochny, made the conscious decision to place it where it would have to dump rockets on its own territory. They could have instead built this new spaceport on the Pacific coast, and avoided inland drop zones, but did not for reasons that escape me.

Tells us a lot about that government and what it thinks of its own people. But then, governments rarely care much about ordinary people, as those who revel in the power of government are generally more interested in that power than in doing what makes sense or is right.

The new colonial movement: China today successfully launched for the first time its new Long March 8 rocket, designed at some point to mimic the Falcon 9 by vertically landing its first stage and reusing it. (Note: link fixed!)

On this launch the rocket had no such recovery capability.

The leaders in the 2020 launch race:

34 China

25 SpaceX

15 Russia

6 ULA

6 Rocket Lab

The U.S. still leads China 40 to 34 in the national rankings.

An evening pause: Silent Night is followed by Robert Clary singing a French carol. All three were actors from the 1960s television comedy series, Hogan’s Heroes, with Klemperer playing the Nazi prison commander, Banner the foolish guard (“I know nothing!!!”), and Clary the French prisoner.

I don’t know exactly when this aired, but it was likely in the late 1960s. It signals the good will fundamental to western civilization. The Germans had only two decades earlier put the world through a horrible war. Still, Americans were glad to hear two Germans immigrants sing this gentle song in their native language, despite the evils that nation had subjected the world to so recently.

The war was over. We are all fallible humans. Time to forgive, and move on.

Hat tip Phill Oltmann.

UPDATE: The police have agreed to back off, if the protesters stay on the sidewalks. At one point one protester smashed the glass on the locked access door that I think is normally open for public access to the legislature.

The key final moment in this protest was when it appears the police used their military vehicle to ram and essentially total one of the trucks that the protesters had placed on the road to block it. The police rammed it, and then backed off to their previous position. The protesters than assembled at that position, pressuring the police hard. This seemed to force the negotiation that caused the police to leave.

Original post:

————————–

It appears that a group showed up to enter the assembly building to watch the legislative session, as legally allowed, and were prevented and attacked. They then sent out a flash mob announcement, and when heavy military style vehicles from the police arrived, announcing that they are an “unlawful assembly”, the protesters blocked their street with their own buses and vehicles.

The live stream is active, and the protest is ongoing. What will happen is unknown, as the protesters are refusing to leave and the police have been bringing in reinforements.

Link here. The article not only provides video and the status of prototype #9 after its fall against the side of the assembly building, it also provides the status of the numerous other prototypes, both of Starship and Super Heavy.

In addition, the article shows the clean-up of the remains of Starship #8 from the landing pad.

All told, it appears that Starship #9 has been repaired from its fall, and is being prepped for a 50,000 foot flight sometime around New Year’s.

Capitalism in space: Lockheed Martin officials announced yesterday that it will buy the rocket engine company Aerojet Rocketdyne for $4.4 billion.

James Taiclet, Lockheed Martin’s president and CEO, said the acquisition gives the company a larger footprint in space and hypersonic technology. He said Aerojet Rocketdyne’s propulsion systems already are key components of Lockheed Martin’s supply chain across several business areas. “The proposed acquisition adds substantial expertise in propulsion to Lockheed Martin’s portfolio,” the company said in a news release.

Aerejet Rocketdyne has been in trouble because it has had problems finding customers for its engines. This acquisition will give Lockheed Martin more technical capabilities should it decide to enter the launch industry with its own rocket.

Embedded below the fold in two parts.

» Read more

Scientists from both the Japanese Hayabusa-2 mission to the asteroid Ryugu and the Chinese Chang’e-5 mission to the Moon announced yesterday the total amount of material they successfully recovered.

The numbers appear to diminish the Japanese success, but that is a mistake. Getting anything back from a rubble-pile asteroid that had never been touched before and is much farther away from Earth than the Moon was a very great achievement. The 5.4 grams is also more than fifty times the minimum amount they had hoped for.

This is also not to diminish the Chinese achievement, They not only returned almost four pounds, some of that material also came from a core sample. They thus got material both from the surface and the interior of the Moon, no small feat from an unmanned robot craft.

Scientists from both nations will now begin studying their samples. Both have said that some samples will be made available to scientists from other countries, though in the case of China it will be tricky for any American scientist to partner with China in this research, since it is by federal law illegal for them to do so.

The uncertainty of science: Breakthough Listen, the project funded to the tune of $100 million by billionaire Yuri Milner with the goal of listening for alien radio signals, in 2019 detected a single radio tone that appeared to be coming from the nearest star, Proxima Centauri.

A team had been using the Parkes radio telescope in Australia to study Proxima Centauri for signs of flares coming from the red dwarf star, in part to understand how such flares might affect Proxima’s planets. The system hosts at least two worlds. The first, dubbed Proxima b upon its discovery in 2016, is about 1.2 times the size of Earth and in an 11-day orbit. Proxima b resides in the star’s “habitable zone,” a hazily defined sector in which liquid water could exist upon a rocky planet’s surface—provided, that is, Proxima Centauri’s intense stellar flares have not sputtered away a world’s atmosphere. Another planet, the roughly seven-Earth-mass Proxima c, was discovered in 2019 in a frigid 5.2-year orbit.

Using Parkes, the astronomers had observed the star for 26 hours as part of their stellar-flare study, but, as is routine within the Breakthrough Listen project, they also flagged the resulting data for a later look to seek out any candidate SETI signals. The task fell to a young intern in Siemion’s SETI program at Berkeley, Shane Smith, who is also a teaching assistant at Hillsdale College in Michigan. Smith began sifting through the data in June of this year, but it was not until late October that he stumbled upon the curious narrowband emission, needle-sharp at 982.002 megahertz, hidden in plain view in the Proxima Centauri observations. From there, things happened fast—with good reason. “It’s the most exciting signal that we’ve found in the Breakthrough Listen project, because we haven’t had a signal jump through this many of our filters before,” says Sofia Sheikh from Penn State University, who helmed the subsequent analysis of the signal for Breakthrough Listen and is the lead author on an upcoming paper detailing that work, which will be published in early 2021. Soon, the team began calling the signal by a more formal name: BLC1, for “Breakthrough Listen Candidate 1.”

The data so far does not suggest this signal was produced by an alien technology. Instead, it likely is a spurious signal from some natural or human source, picked up by accident, as was the SETI “Wow” signal that for years puzzled astronomers until they traced it to a comet.

However, as they do not yet have an explanation, it is a mystery of some importance.

Capitalism in space: SpaceX today successfully completed its 25th orbital launch in 2020, using its Falcon 9 rocket to put an American spy satellite into orbit.

The first stage successfully landed at Cape Canaveral, completing its fifth flight.

Not only is 25 launches in a single year a new record for SpaceX, it is also four more launches than the company predicted it would achieve in 2020.

This was also the 40th successful American orbital launch in 2020, the first time since 1968 that the U.S. has had that many launches. In 1968 the launches were almost all dictated by the government, on rockets controlled by the government. Today, the rockets are all privately designed and owned, with the small number of government launches occurring with the government merely the customer buying a product.

The leaders in the 2020 launch race:

33 China

25 SpaceX

15 Russia

6 ULA

6 Rocket Lab

The U.S. now leads China 40 to 33 in the national rankings. The rankings also should not change significantly in the last two weeks of the year, as the U.S. has no more scheduled launches and China and Russia only one.

An evening pause: I think this makes for a nice start of this year’s set of Christmas season evening pauses.

Note that though this piece is available on youtube, I specifically chose to embed it from Vimeo. It is time to no longer rely solely on google, if at all possible.

And they expect the public to trust them? The election board of Maricopa County has decided to defy the subpoenas issued by the state’s legislature for getting a full audit of its election results, and will instead file a lawsuit against those legislators.

It seems to me that if there was nothing wrong with the Dominion tabulators and the count, than the board would welcome this audit. That they are stonewalling it is if anything evidence that there is likely something they are hiding.

We have now reached the Rubicon. Are our elected officials truly in charge, or are they to be ordered around by unelected bureaucrats like mere serfs? If the state legislature and the governor does not act here, then they are no more than figureheads, and we are now ruled by fiat, by the bureaucracy. Arizona does not have a democracy ruled by law any longer.

In order to better constrain its orbit, the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii has obtained new photographs of Hayabusa-2’s next target asteroid, 100-foot-wide 1998 KY26.

This asteroid is predicted to approach to within 0.47 AU of Earth in mid to late December 2020, giving us a rare opportunity that comes only once every three and a half years. However, the diameter of 1998 KY26 is estimated to be no more than 30 meters, and thus its brightness is so dim that ground-based observations of the asteroid are difficult without a very large telescope.

The observations with the Subaru Telescope were conducted upon the request of the Institute for Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), JAXA. And as a result, 1998 KY26 was photographed in the direction of the constellation Gemini as a 25.4-magnitude point of light with a measurement uncertainty of 0.7 mag. The positional data collected during these observations will be used to improve the accuracy of the orbital elements of the asteroid. Similar observations were conducted with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) of the European Southern Observatory (ESO).

If all goes right Hayabusa-2 will rendezvous with 1998 KY26 in the summer of 2031.

Because a repair would delay the first SLS launch for months if not a year, NASA has decided to fly Orion on that November ’21 mission with failed electronics power unit.

In a Dec. 17 statement, NASA said it had decided to “use as is” one of eight power and data units (PDU) on the Orion spacecraft, which provide communications between the spacecraft’s computers and other components. One of two redundant channels in one of two communications cards in that PDU is not working.

…NASA, in its statement about deciding not to replace the PDU, did not go into details about the repair options, but said that the risks of damaging the spacecraft during the PDU repair outweighed any loss of data should the unit completely malfunction.

Engineers, the agency stated, “determined that due to the limited accessibility to this particular box, the degree of intrusiveness to the overall spacecraft systems, and other factors, the risk of collateral damage outweighed the risk associated with the loss of one leg of redundancy in a highly redundant system.”

“NASA has confidence in the health of the overall power and data system, which has been through thousands of hours of powered operations and testing,” the agency added, noting that the PDU in question was still “fully functional.”

Let’s then assess Orion. The contract was issued to Lockheed Martin in 2006. In the fourteen years since Congress has spent about $17 billion on this manned capsule. In that time it has flown once, during a test flight that was intended to test its heat shield, even though when that flight happened NASA had already decided that it was not going to use the heat shield design it was testing.

Orion’s second flight in November ’21 will be unmanned, but it will be flying with this failed unit. The next time it is supposed to fly will be in ’24, when NASA is hoping to send astronauts on a lunar landing missions. By that time NASA will have spent about $20 billion on Orion, and gotten two test capsules (both unrepresentative of the flight model) plus one manned mission.

Would you fly on this capsule under these circumstances? I wouldn’t, especially considering the non-track record of its rocket, SLS.

As the taxpayer, do you think you’ve gotten your money’s worth from this capsule? I don’t. I think it has been an ungodly waste of money, and a demonstration of the incapability of NASA and the big space contractors Boeing and Lockheed Martin of getting anything accomplished. Depend on them, and you will never go anywhere.

All trust is lost: John Poulos, the CEO of Dominion, the company that provided the software and tabulators used to count ballots in numerous states and which have been accused of being unreliable and subject to vote tampering, responded to those charges in a legislative hearing in Michigan.

Poulos told legislators in Michigan via video link on Dec. 15 that his company’s machines and software were not involved in any “switched or deleted votes.” He said that because of a rule change, the machine programming needed to be updated in October. But Antrim County officials failed to update all 18 tabulators, meaning some had new programming while some still had the old programming.

Officials then forgot to conduct the logic and accuracy tests on the programming, he said. A third error took place when a contracting firm in October programmed the tabulators in a way that allowed memory cards with both the old and new programming to count votes. “If all of the tabulators had been updated as per procedure, there wouldn’t have been any error in the unofficial reporting,” he said.

Poulos also said any discrepancies with the counts from its machines can be investigated by referencing paper ballots and insisted that all audits and recounts of Dominion technology used in the 2020 election have “validated the accuracy and reliability” of the election results. “No one has produced credible evidence of vote fraud or vote switching on Dominion systems because these things have not occurred,” he insisted.

In the normal civilized America that once existed, I would be more prone to believe him. Considering the four years of outright lying that Democratic Party officials and their supporters have subjected us to, from a Russian collusion hoax to a fake Ukrainian impeachment of Trump to endless lies relating to COVID-19 lock downs to lying about the actual spying on Trump by the Obama administration to lying to the FISA court to obtain fake warrants to lying about Brett Kavanaugh and others, it is unreasonable for anyone to trust this man’s word. It is worthless.

And my opinion in this is not alone. Consider this response to his testimony by one Michigan Republican leader:

Linda Lee Tarver, president of the Republican Women’s Federation of Michigan and former election integrity liaison in the Michigan Secretary of State’s Office, said Thursday that Dominion chief John Poulos’s recent testimony left more questions unanswered than it clarified.

Tarver, who testified at a Michigan election integrity hearing on Dec. 2, said Poulos’s Dec. 15 testimony to lawmakers boiled down to reiterating that “human error” was to blame for an initial Election Day vote discrepancy in Michigan’s Antrim County, where Dominion products were used.

She said some of the questions that Poulos did not address include whether poll workers received proper training on the Dominion system, concerns about whether vote tabulators could use a USB stick to add votes to a candidate, and how prone Dominion systems are to hacking. Tarver also said chain-of-custody questions remained unanswered, and raised concerns about the ability of Dominion machines to connect to the Internet. Poulos confirmed that a small percentage of Dominion machines have Internet connectivity.

The only way to satisfy Republicans that the vote was honest is to allow a full and careful audit by their elected officials, to prove no fraud took place. Of course Democrats should be allowed to participate and question everything, but under no circumstances can they be allowed to dictate any terms on such an audit.

Click for full resolution image.

The cool image to the right, reduced and annotated to post here, was a captioned photo released by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) science team earlier this week. Taken by MRO’s high resolution camera, it shows in color a beautifully stair-stepped mesa located in an unnamed 22-mile-wide equatorial crater in Arabia Terra, the large transitional zone between the lowland northern plains and the southern cratered highlands. As the caption notes,

Several craters in Arabia Terra are filled with layered rock, often exposed in rounded mounds. The bright layers are roughly the same thickness, giving a stair-step appearance. The process that formed these sedimentary rocks is not yet well understood. They could have formed from sand or volcanic ash that was blown into the crater, or in water if the crater hosted a lake.

If volcanic ash, the layers are signalling a series of equal eruptions of equal duration, which seems unlikely. Water is also puzzling because of the equatorial location. Like yesterday’s mystery cool image, water is only likely here at a time when the red planet’s rotational tilt, its obliquity, was much higher, placing this at a higher latitude than it is today.

Regardless, make sure you look at the full image here. This crater floor is chock-full of more such terraced mesas, some of which are even more striking than the sample above.

I have also posted below the MRO context camera photo of the entire crater.

» Read more