September 10, 2019 Zimmerman/Batchelor

Embedded below the fold in two parts.

» Read more

Embedded below the fold in two parts.

» Read more

Very brief descriptions, with appropriate links, of current or recent news items.

Embedded below the fold in two parts.

» Read more

The uncertainty of science: Astronomers now believe they have detected water in the atmosphere of an exoplanet that is also in habitable zone.

A new study by Professor Björn Benneke of the Institute for Research on Exoplanets at the Université de Montréal, his doctoral student Caroline Piaulet and several of their collaborators reports the detection of water vapour and perhaps even liquid water clouds in the atmosphere of the planet K2-18b.

…This exoplanet is about nine times more massive than our Earth and is found in the habitable zone of the star it orbits. This M-type star is smaller and cooler than our Sun, but due to K2-18b’s close proximity to its star, the planet receives almost the same total amount of energy from its star as our Earth receives from the Sun.

The size and mass of the this exoplanet means life as we know it probably does not exist there, either on its surface or in its atmosphere. Nonetheless, with water and the right amount of energy, anything is still possible.

Space is hard: Eric Berger at Ars Technica reported yesterday that the parachute issues for Europe’s ExoMars 2020 mission are far more serious that publicly announced.

The project has had two parachute failures during test flights in May and then August. However,

The problems with the parachutes may be worse than has publicly been reported, however. Ars has learned of at least one other parachute failure during testing of the ExoMars lander. Moreover, the agency has yet to conduct even a single successful test of the parachute canopy that is supposed to deploy at supersonic speeds, higher in the Martian atmosphere.

Repeated efforts to get comments from the project about this issue have gone unanswered.

Their launch window opens in July 2020, only about ten months from now. This is very little time to redesign and test a parachute design. Furthermore, they will only begin the assembly of the spacecraft at the end of this year, which is very very late in the game.

When the August test failure was confirmed, I predicted that there is a 50-50 chance they will launch in 2020. The lack of response from the project above makes me now think that their chances have further dropped, to less than 25%.

Japan today scrubbed the launch of its unmanned HTV cargo freighter to ISS due to a launchpad fire that broke out only three and half hours before liftoff.

There is as yet no word on the cause of the fire, or how much damage it caused. Nor have they said anything about rescheduling the launch.

This would have been Japan’s second launch in 2019, a drop from the average of 4 to 6 in the last five years.

The pit to the right could almost be considered the first “cool image” on Behind the Black. It was first posted on June 20, 2011. Though I had already posted a number of very interesting images, this appears to be the first that I specifically labeled as “cool.”

The image, taken by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), had been requested by a seventh grade Mars student team at Evergreen Middle School in Cottonwood, California, and shows a pit on the southeastern flank of the volcano Pavonis Mons, the middle volcano in Mars’ well-known chain of three giant volcanoes. A close look at the shadowed area with the exposure cranked up suggests that this pit does not open up into a more extensive lava tube.

What inspired me to repost this image today was the release of a new image from Mars Odyssey of this pit and the surrounding terrain, taken on July 31, 2019 and shown below to the right.

» Read more

Capitalism in space: SES yesterday announced that it has awarded SpaceX’s Falcon 9 the launch contract for the next seven satellites in its next generation communications constellation.

This is a big win for SpaceX, made even more clear by a briefing held yesterday with reporters by Arianespace CEO Stéphane Israel. In that briefing Israel outlined that company’s upcoming launch contracts, where he also claimed that this launch manifest is so full he had to turn down SES’s launch offer.

Because of its full manifest, Arianespace was unable to offer SES launch capacity in 2021 for its next generation of medium Earth orbit satellites, mPOWER. SES announced plans Sept. 9 to fly mPOWER satellites on SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets from Florida’s Cape Canaveral. Arianespace launched the 20 satellites in the SES O3B constellation.

It was important to SES to launch in 2021, Israel said. Given Arianespace’s full manifest, it was difficult “to offer the guarantee they were asking for,” he added.

If you believe that I have a bridge I want to sell you. Arianespace has been struggling to get launch contracts for its new Ariane 6 rocket. They have begun production on the first fourteen, but according Israel’s press briefing yesterday, Ariane 6 presently only has eight missions on its manifest. That means that six of the rockets they are building have no launch customers. I am sure they wanted to put those SES satellites on at least some of those rockets, and couldn’t strike a deal because the expendable Ariane 6 simply costs more than the reusable Falcon 9.

According to a story today in official Chinese state-run media, Yutu-2 traveled another 284.99 meters during its ninth lunar day on the surface of the Moon, and has now been placed in hibernation in order to survive the long lunar night.

The story provides no further information, including saying nothing about the strange and unusual material the rover supposedly spotted during this time period.

Vector has withdrawn from an Air Force launch contract, allowing the military to reassign the contract to another new launch startup, Aevum.

The Agile Small Launch Operational Normalizer (ASLON)-45 space lift mission had been originally awarded to Vector Launch Aug. 7. But Vector formally withdrew Aug. 26 in the wake of financial difficulties that forced the company to suspend operations and halt development of its Vector-R small launch vehicle.

The Rocket Systems Launch Program — part of the Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center Launch Enterprise — used a Federal Acquisition Regulation “simplified acquisition procedure” to expedite another agreement with a different contractor, the Air Force said in a news release. Aevum’s contract is $1.5 million higher than the one that had been awarded to Vector.

The full scope of Vector’s problems still remain unclear. My industry sources tell me that there was absolutely no malfeasance at all behind the resignation of former CEO Jim Cantrell. From what I can gather, the problems appear to stem from issues of engineering with their rocket, combined with an investor pull-back due to those problems.

Either way, Vector is no longer among the leaders in the new smallsat launch industry, and in fact appears to be fading fast.

Embedded below the fold in two parts.

The first segment is especially worth listening to, as I blast the leftist mob rule that is killing TNT, advocating climate fraud, and is now trying to use that climate fraud, mostly by Democratic politicians, to advocate the destruction of freedom and our capitalist society. In fact, after we finished that segment John Batchelor took me to task for calling these Democrats “fascists” twice. John didn’t dispute my use of the word, nor was he trying to shut me up. He merely said using the word twice in one segment isn’t good radio, and to this I kind of agree.

Then again, these Democrats are fascists, and more people should be saying it.

» Read more

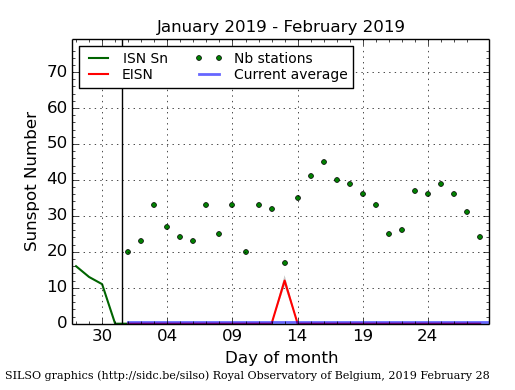

Last month I titled my sunspot update “Almost no sunspots,” as there were only two sunspots for the entire month of July, with one having the polarity for the next solar maximum.

August however beat July, with only one sunspot for the month, and none linked to the next maximum. To the right is the Silso graph of sunspot activity for August, showing just one sunspot for the month, on only one day, August 13.

Below is NOAA’s August graph of the overall sunspot cycle since 2009, released by NOAA today and annotated to give it some context.

» Read more

A new theory proposes that some of the smaller high rimmed methane lakes on Titan were formed when underground nitrogen warmed and exploded, forming the basin in which the methane ponded.

Most existing models that lay out the origin of Titan’s lakes show liquid methane dissolving the moon’s bedrock of ice and solid organic compounds, carving reservoirs that fill with the liquid. This may be the origin of a type of lake on Titan that has sharp boundaries. On Earth, bodies of water that formed similarly, by dissolving surrounding limestone, are known as karstic lakes.

The new, alternative models for some of the smaller lakes (tens of miles across) turns that theory upside down: It proposes pockets of liquid nitrogen in Titan’s crust warmed, turning into explosive gas that blew out craters, which then filled with liquid methane. The new theory explains why some of the smaller lakes near Titan’s north pole, like Winnipeg Lacus, appear in radar imaging to have very steep rims that tower above sea level – rims difficult to explain with the karstic model.

This is a theory that has merit. It also must be treated with skepticism, as our knowledge of Titan remains at this time very superficial, even with the more detailed information garnered from Cassini.

According to K. Sivan, the head of ISRO, India’s space agency, their Chandrayaan-2 orbiter has captured a thermal image of Vikram on the lunar surface, pinpointing the lander’s location.

They have not released the image. According to reports today, they do not yet know the lander’s condition, and have not regained communications. Reports late yesterday had quoted K.Sivan as saying “It must have been a hard-landing.” That quote is not in today’s reports.

In watching the landing and the subsequent reports out of India, it appears that India is having trouble dealing with this failure. To give the worst example, I watched a television anchor fantasize, twenty minutes after contact had been lost, that the lander must merely be hovering above the surface looking for a nice place to land. Most of the reports are not as bad, but all seem to want to minimize the failure, to an extreme extent.

Their grief is understandable, because their hopes were so high. At the same time, you can’t succeed in this kind of challenging endeavor without an uncompromising intellectual honesty, which means you admit failure as quickly as possible, look hard at the failure to figure out why it happened, and then fix the problem. If India can get to that place it will be a sign that they are maturing as a nation. At the moment it appears they are not quite there.

Vikram, India’s first attempt to soft land on the Moon, apparently has failed, with something apparently going wrong in the very last seconds before landing.

As I write this they have not officially announced anything, but the live feed shows a room of very unhappy people.

It is possible the lander made it and has not yet sent back word, but such a confirmation should not take this long.

India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, was given a very short briefing by K. Sivan, head of ISRO, and then apparently left without comment. This I found an interesting contrast to the actions of Israel’s prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu when its lunar lander Beresheet failed in landing earlier this year. Netanyahu came out to comfort the workers in mission control, congratulating them for getting as far as they had. Modi apparently simply left. UPDATE: Modi has reappeared to talk to the children who had won a contest to see the landing as well as people in mission control. After making a public statement he has now left.

They are now confirming that communications was lost at 2.1 kilometers altitude, which was just before landing. They are analyzing the data right now to figure out what went wrong.

The new colonial movement: I have embedded below the live stream of India’s attempt today to land its Vikram lander on the Moon, broadcast by one of their national television networks.

The landing window is from 4:30 to 5:30 pm Eastern. This live stream is set to begin about 3 pm Eastern.

If you want to watch ISRO’s official live stream you can access it here.

Some interesting details: Vikram is named after Vikram A. Sarabhai, who many consider the founder of India’s space program. The lunar rover that will roll off of Vikram once landing is achieved is dubbed Pragyan, which means “wisdom” in Sanskrit. Both are designed to operate on the Moon for one lunar day.

The landing site will be about 375 miles from the south pole.

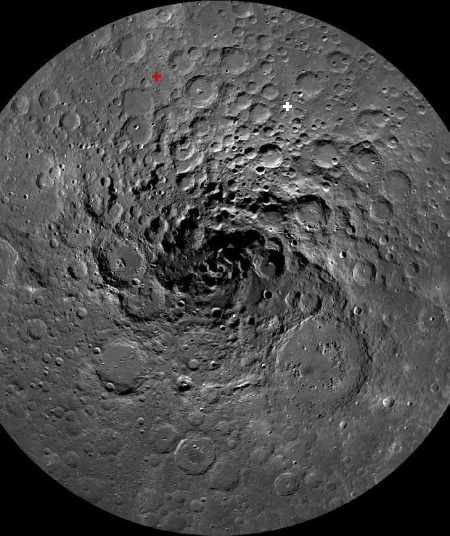

That spot is a highland that rises between two craters dubbed Manzinus C and Simpelius N. On a grid of the moon’s surface, it would fall at 70.9 degrees south latitude and 22.7 degrees east longitude.

The white cross on the image to the right is where I think this site is. The secondary landing site is indicated by the red cross.

According to FAA regulatory documents, SpaceX has updated its development plan for Starship, including changes in its overall plans for its Boca Chica facility.

The document also lays out a three-phase test program, which it says “would last around 2 to 3 years”:

Phase 1: Tests of ground systems and fueling, a handful of rocket engine test-firings, and several “small hops” of a few centimeters off the ground. The document also includes graphic layouts, like the one above, showing the placement of water tanks, liquid methane and oxygen storage tanks (Starship’s fuels), and other launch pad infrastructure.

Phase 2: Several more “small hops” of Starship, though up to 492 feet (150 meters) in altitude, and later “medium hops” to about 1.9 miles (3 kilometers). Construction of a “Phase 2 Pad” for Starship, shown below, is also described.

Phase 3: A few “large hops” that take Starship up to 62 miles (100 kilometers) above Earth — the unofficial edge of space — with high-altitude “flips,” reentries, and landings.

The first phase is now complete, with the company shifting into Phase 2.

Boca Chica meanwhile is no longer being considered a spaceport facility. Instead, its focus will now be a development site for building Starship and Super Heavy.

The European Space Agency (ESA) this week released the results of its investigation into the July 10, 2019 launch failure of Arianespace’s Vega rocket, the first such failure after 14 successful launches.

The failure had occurred about the time the first stage had separated and the second stage Z23 rocket motor was to ignite. The investigation has found that the separation and second stage ignition both took place as planned, followed by “a sudden and violent event” fourteen seconds later, which caused the rocket to break up.

They now have pinned that event to “a thermo-structural failure in the forward dome area of the Z23 motor.”

The report says they plan to complete corrective actions and resume launches by the first quarter of 2020.

Embedded below the fold in two parts.

» Read more

They’re coming for you next: A local Pennsylvania township has shut down an entire voluntary fire company because it refused to blacklist a member who also happened to have expressed interest in joining the Proud Boys organization.

Officials in Haverford Township, in Delaware County, were informed on Aug. 12 that a volunteer with the Bon Air Fire Company was affiliated with “an organization described as an extremist group,” the township’s manager David Burman wrote in a statement released Thursday.

The township immediately launched an investigation, which included interviewing the volunteer, who admitted he was involved with the Proud Boys, Burman said. The volunteer revealed he had attended social gatherings hosted by the group and had passed two of the group’s four initiation steps, “which includes hazing.”

Burman’s statement quoted the group’s “self-proclaimed basic tenet,” posted on their website, that they are “Western chauvinists who refuse to apologize for creating the modern world.” The proclamation belongs to the Proud Boys, who “are known for anti-Muslim and misogynistic rhetoric,” according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which designates them as a hate group. Women and transgender men are not allowed in the group.

While the volunteer “indicated that he had attempted to distance himself from the group in recent months” Burman and a police official met with Bon Air Fire Company officials on Aug. 14 to address “the seriousness of this matter and urged the fire company to address it.”

Burman said he was informed the next day that the volunteer had offered his resignation, but the Bon Air Fire Company chief had refused to accept it. A week later, Burman said he received an email that said the fire company’s board had “found no basis for terminating the volunteer’s membership.”

First, the accusations of bigotry by the Southern Poverty Law Center are pure slander and libel. There is no evidence of this. The Proud Boys are admittedly a male-only organization, but so what? This isn’t proof of bigotry, no matter what the modern idiotic political correct leftist interpretation claims. And the organization’s proud favoring of western civilization over other cultures, such as Islam, actually has strong empirical proof, for anyone who has read any history at all. These slanders are part of Obama’s legacy of hate, whereby liberals now have the freedom to label anyone who disagrees with them bigots and hate-mongers, without any evidence.

I applaud the fire company for standing up for the freedom of speech of one of its members. I wish that there would be an outpouring of support for them in this locality in Pennsylvania. They should be honored for defending freedom, and telling the local petty dictators on the township’s government to go to hell.

Cool image time! In my review of the most recent download of images from Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s (MRO) the high resolution camera, I found a very startling (and cool) image of some dramatic terraced Martian hills, taken on July 30, 2019. I wanted to post it here, but decided to first do some more digging, and found that an earlier image, taken in 2017, showed more of this particular hill. It is this earlier image posted to the right, cropped and reduced.

Don’t ask me to explain the geology that caused this hill to look as it does. I can provide some basic knowledge, but the details and better theories will have to come from the scientists who are studying this feature (who unfortunately did not respond to my request for further information).

What I can do is lay out what is known about this location, as indicated by the red box in the overview map below and to the right, and let my readers come up with their own theories. The odds of anyone being right might not be great, but it will be fun for everyone to speculate.

» Read more

Fascists: When asked by CNN interviewers during that network’s seven hour pro-Democratic climate forum yesterday what they would do to prevent global warming, it appears that the primary solution by every Democratic presidential candidate was to ban things.

Democrats appearing at CNN’s marathon 7-hour global warming forum have a plan to solve a changing climate: Ban everything!

Over the course of the television extravaganza, Democrats’ leading 2020 presidential candidates floated a variety of proposals to cut Americans’ energy use and, ostensibly, to stop the climate from changing. Among them: Bans on plastic straws, red meat, incandescent lightbulbs, gas-powered cars, nuclear energy, off-shore drilling, fracking, natural gas exports, coal plants, and even “carbon” itself.

The article goes on to detail each candidate’s banning proposals, all of which were similar, mindless, and based on an incredible level of ignorance about the climate and science. Bernie Sanders however probably gave us the most revealing and honest glimpse into all their mindsets with his suggestion that human life itself was the problem.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) went the furthest, saying we should try to minimize human life itself to help the environment. Sanders said he’d use taxpayer money to help fund 3rd world population control programs: “The answer has everything to do with the fact that women in the United States of America, by the way, have a right to control their own bodies and make reproductive decisions. And the Mexico City agreement, which denies American aid to those organizations around the world that allow women to have abortions or even get involved in birth control to me is totally absurd.” [emphasis mine]

No one should be surprised by this. Every socialist/communist/totalitarian movement in the past has always led inevitably to the killing of millions. For them, their ideas are much more important than people, and should those people get in the way, well then, they must be removed, by force and by gas chambers if necessary.

Be prepared. Should one of these power-hungry leftists win the White House they will be coming for you next.

Language scientists think they have determined that the universal bit rate for transmitting information across multiple languages is about 39 bits per second.

Scientists started with written texts from 17 languages, including English, Italian, Japanese, and Vietnamese. They calculated the information density of each language in bits—the same unit that describes how quickly your cellphone, laptop, or computer modem transmits information. They found that Japanese, which has only 643 syllables, had an information density of about 5 bits per syllable, whereas English, with its 6949 syllables, had a density of just over 7 bits per syllable. Vietnamese, with its complex system of six tones (each of which can further differentiate a syllable), topped the charts at 8 bits per syllable.

Next, the researchers spent 3 years recruiting and recording 10 speakers—five men and five women—from 14 of their 17 languages. (They used previous recordings for the other three languages.) Each participant read aloud 15 identical passages that had been translated into their mother tongue. After noting how long the speakers took to get through their readings, the researchers calculated an average speech rate per language, measured in syllables/second.

Some languages were clearly faster than others: no surprise there. But when the researchers took their final step—multiplying this rate by the bit rate to find out how much information moved per second—they were shocked by the consistency of their results. No matter how fast or slow, how simple or complex, each language gravitated toward an average rate of 39.15 bits per second, they report today in Science Advances. In comparison, the world’s first computer modem (which came out in 1959) had a transfer rate of 110 bits per second, and the average home internet connection today has a transfer rate of 100 megabits per second (or 100 million bits). [emphasis mine]

When I went to Russia the first time in 1995 I used to joke with my caving friends there that the real reason the U.S. won the cold war was that English words routinely used one syllable for the three required by Russian and thus we could get things done in one third the time. I would start listing comparable words, (for example “good” vs “khah-rah-shoh” and “please” vs “pa-ZHAL-sta”) and challenge them to come up with any example where the Russian word had fewer syllables. It drove them crazy because they couldn’t do it.

I was joking of course. It makes sense that the information rates should actually be pretty much the same, as this study suggests. However, the highlighted words also suggest that the subtle differences should also not be ignored.

They’re coming for you next: The San Francisco Board of Supervisors, all Democrats, yesterday voted unanimously to declare the National Rifle Association a domestic terrorist organization.

[The resolution blames the] NRA … for causing gun violence. “The National Rifle Association musters its considerable wealth and organizational strength to promote gun ownership and incite gun owners to acts of violence,” the resolution reads. The resolution also claims that the NRA “spreads propaganda,” “promotes extremist positions,” and has “through its advocacy has armed those individuals who would and have committed acts of terrorism.”

In addition to calling the NRA a domestic terrorist organization, the Board of Supervisors called on the city and county of San Francisco to “take every reasonable step to limit … entities who do business with the City and County of San Francisco from doing business” with the NRA.

You can read the resolution here [pdf]. Its aim is to blacklist this legal organization made of about five million Americans. It also aims to forbid any legal agreements between any businesses in San Francisco and the NRA, as well as encourage all other city, state, and federal governments to do the same.

Ah, blacklists! I remember them well. There was once a time that Democrats considered blacklists to be the font of all evil, and proof that anyone who suggested them was a fascist. Now that the left proposes such things they stand for justice and righteousness.

Nor is this the only example. Recently several Hollywood television actors called for the publication of all attendees to a Trump fundraiser in Beverly Hills, so that they could make a list of people to blacklist. Fortunately, a lot of other Hollywood stars balked, criticizing the idea.

Nonetheless, this is where the leftist Democratic Party is headed. Either you agree with them, or you must be squelched, in every way possible.

The Hong Kong government today announced that it is withdrawing the extradition bill demanded by China that sparked Hong Kong protests.

Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s chief executive, said Wednesday that the government would withdraw a contentious extradition bill that ignited months of protests in the city, moving to quell the worst political crisis since the former British colony returned to Chinese control 22 years ago.

The move eliminates a major objection among protesters, but it was unclear if it would be enough to bring an end to intensifying demonstrations, which are now driven by multiple grievances with the government.

“Incidents over these past two months have shocked and saddened Hong Kong people,” she said in an eight-minute televised statement broadcast shortly before 6 p.m. “We are all very anxious about Hong Kong, our home. We all hope to find a way out of the current impasse and unsettling times.”

Her decision comes as the protests near their three-month mark and show little sign of abating, roiling a city known for its orderliness and hurting its economy.

The article suggests that the protests will still go on, that the “genie is out of the bottle.” I am not so sure.

Regardless, what this means is that, as of now, China is admitting that its effort to eliminate Hong Kong’s democratic systems and fold it completely into the communist power structure of the mainland has failed. This does not mean that China will stop trying, merely that they will now pause in this effort.

The arriving dark age: It appears that the protests in Hawaii that are preventing the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope might end up killing the telescope completely.

The problem is twofold. First, the Democratic-controlled government in Hawaii is willing to let the protesters run the show, essentially allowing a mob to defy the legal rulings of the courts:

The Native Hawaiian protesters blocking the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) on the summit of Mauna Kea appear to have settled in for the long haul. After 2 months of protests, their encampment on the Mauna Kea access road has shops, a cafeteria, and meeting spaces. “It’s like a small village,” says Sarah Bosman, an astronomer from University College London who visited in July. “There are signs up all over the island. It was a bit overwhelming really.”

Second, there is opposition to the alternate backup site in the Grand Canary Islands, both from local environmental groups and from within the consortium that is financing the telescope’s construction.

Astronomers say that the 2250-meter-high site, about half as high as Mauna Kea, is inferior for observations. Canada, one of six TMT partners—which also include Japan, China, India, the California Institute of Technology, and the University of California—is especially reluctant to make the move and could withdraw from the $1.4 billion project, which can ill afford to lose funding. Finally, an environmental group on La Palma called Ben Magec is determined to fight the TMT in court and has succeeded in delaying its building permit. It says the conservation area that the TMT wants to build on contains archaeological artifacts. “They’re willing to fight tooth and nail to stop TMT,” says Thayne Currie, an astronomer at the NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California.

We now live in a culture that is opposed to new knowledge. It is also a culture that prefers mob rule, giving power to the loudest and possibly most violent protesters, while treating the law as a mere inconvenience to be abandoned at the slightest whim of those mobs.

If this doesn’t define a dark age, I’m not sure what does.

The new colonial movement: India’s Vikram lunar lander today made its second and last orbital change, preparing itself for landing on the Moon on September 7.

The orbit of Vikram Lander is 35 km x 101 km. Chandrayaan-2 Orbiter continues to orbit the Moon in an orbit of 96 km x 125 km and both the Orbiter and Lander are healthy.

With this maneuver the required orbit for the Vikram Lander to commence it descent towards the surface of the Moon is achieved. The Lander is scheduled to powered descent between 0100 – 0200 hrs IST on September 07, 2019, which is then followed by touch down of Lander between 0130 – 0230 hrs IST

They plan to roll the rover Pragyan off of Vikram about two hours after landing.

This article provides a nice overview of the mission.

The Conservative Party in Great Britain today expelled 21 members who voted against Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s plan to exit the European Union, deal or no deal.

[The expulsion plan was announced] just hours after lawmakers in Britain passed legislation designed to stop Johnson from taking the UK out of the European Union without a formal deal. The House of Commons earlier Tuesday passed a bill allowing members of Parliament to introduce legislation forcing Johnson to ask for a three-month extension from the EU if a deal is not made by Oct. 31, the Brexit deadline.

The bill passed in a 328 to 301 vote, with 21 members of the governing Conservative Party defecting and joining the opposition party, The Guardian reported.

Johnson has also announced that he will call for general elections, to decide if his party should remain in power. At the moment it appears he does not have a majority in parliament to rule.

At the same time, Johnson has soared in the polls for his hardline exit strategy, and it also appears this strategy is garnering him international political support.

If Johnson wins in the elections, he will have succeeded in purging his party of the equivalent of what conservatives in the U.S. call RINOs, fake conservatives who mouth the right thing but don’t really mean it and when push comes to shove always betray the people who voted for them. This will put Johnson in a very strong political position for doing what he was chosen to do, uphold the choice of the electorate when they voted to leave the European Union.

SpaceX today issued an explanation for why it had not responded when ESA officials had asked them to change the orbit of one of its Starlink smallsats to protect against a possible collision with ESA’s Aeolus spacecraft.

SpaceX, in a statement Sept. 3, said it was aware of a potential conjunction Aug. 28 and communicated with ESA. At that time, though, the threat of a potential collision was only about 1 in 50,000, below the threshold where a maneuver was warranted. When refined data from the U.S. Air Force increased the probability to within 1 in 1,000, “a bug in our on-call paging system prevented the Starlink operator from seeing the follow on correspondence on this probability increase,” a company spokesperson told SpaceNews.

“SpaceX is still investigating the issue and will implement corrective actions,” the spokesperson said of the glitch. “However, had the Starlink operator seen the correspondence, we would have coordinated with ESA to determine best approach with their continuing with their maneuver or our performing a maneuver.”

This incident increasingly strikes me as a tempest in a teapot created by ESA for any number of reasons, including their overall dislike of SpaceX (for generally making all government-run space programs look foolish). There is also this quote from an ESA official in the article above:

“The case just showed that, in the absence of traffic rules and communication protocols, collision avoidance has to rely on the pragmatism of the involved operators,” Krag said. “This is done today by exchange of emails. Such a process is not viable any longer with the increase of space traffic.” He said that, if the Space Safety initiative is funded, ESA would like to demonstrate automated maneuver coordination by 2023. [emphasis mine]

I can just see ESA officials drooling with eager anticipation the coming of more “traffic rules and communication protocols,” partly inspired by this fake crisis they just created. Imposing more rules and getting increased funding is what they do best, since it certainly isn’t exploring space with creative and efficient innovation.

In the continuing political battle in the British parliament over the decision by the voters to leave the European Union and prime minister Boris Johnson’s effort to abide by that decision quickly, a member of his Tory Party defected from that party today in a public stunt.

Boris Johnson has seen his one-vote Commons majority vanish before his eyes, as a statement by the prime minister to parliament was undermined by the very public defection of the Conservative MP Phillip Lee to the Liberal Democrats.

The stunt, in which the pro-remain Bracknell MP walked across the chamber to the Lib Dem benches flanked by two of his new colleagues, happened as Johnson updated the Commons on last month’s G7 summit, a statement devoted mainly to Brexit.

At the start of a crucial day in the Commons, Johnson condemned a backbench plan aimed at delaying Brexit to avert a no-deal departure, calling it a “surrender bill”. Jeremy Corbyn responded by criticising the PM’s language. MPs will vote on Tuesday evening on whether to take control of the order paper to allow the passage of the bill. Johnson has promised to seek a general election if they do so.

It is very clear that Great Britain has the same political problem as the United States: an entrenched elitist power structure that doesn’t wish to abide by the popular will, and is willing to do almost anything to maintain its power, even if that means corrupting or even destroying the democratic institutions that have made western civilization possible.

Japan’s Hayabusa-2 space probe automatically entered safe mode for one day on August 29, causing engineers to postpone a planned operation set for Sept 5.

Hayabusa2 is equipped with four reaction wheels that are used to control the posture of the spacecraft, and posture control is usually performed using three of these reaction wheels. On August 29, the back-up reaction wheel that has not been used since October last year was tested, and an abnormal value (an increased torque) as detected. The spacecraft therefore autonomously moved into the Safe-Hold state. Details of the cause of the abnormal torque value are currently under investigation. On August 30, restoration steps were taken and the spacecraft returned to normal. However, as the spacecraft moved away from the home position due to entering Safe-Hold, we are currently having to return to the home position. We will return to the home position this weekend.

The attitude of the spacecraft is controlled by three reaction wheels as before. Entering the Safe-Hold state is one of the functions employed to keep the spacecraft safe, which means that procedures have worked normally.

In this case it is very clear that this event actually demonstrated that the spacecraft’s systems are operating properly to prevent it from becoming lost. However, the event also underlined the urgency of getting its samples from the asteroid Ryugu back to Earth.

Capitalism in space: The private commercial lunar lander company PTScientists has been purchased by an unknown investor, thereby avoid liquidation after declaring bankruptcy in July.

Berlin-based PTScientists and the law firm Görg, which handled the company’s bankruptcy administration, announced the acquisition in a German-language statement published Sept. 2. The announcement said neither the company buying PTScientists nor the purchase price would be disclosed, but that the deal was effective Sept. 1.

The acquisition, the announcement stated, allows PTScientists to retain its staff of about 60 people who had been working on lunar lander concepts, including a study for the European Space Agency of a mission to send a lander to the moon to perform experiments for in-situ resource utilization. ESA awarded that study to a team that included PTScientists as well as launch vehicle company ArianeGroup in January.

It seems that someone decided that this company was worth saving, and that it (and the private construction of private planetary missions) has the potential to make them money in time.