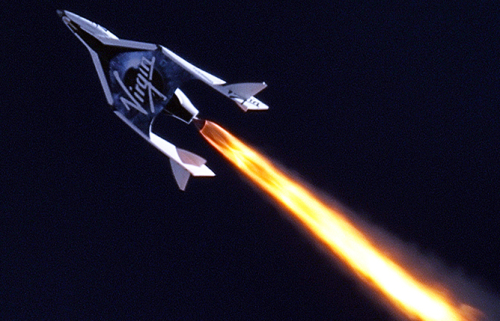

The bell of freedom rings in space

“Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all

the inhabitants thereof.” Photo credit: William Zhang

Not surprisingly the mainstream press today was agog with hundreds of stories about Richard Branson’s suborbital space flight yesterday on Virgin Galactic’s VSS Unity spaceplane.

The excitement and joy over this success is certainly warranted. Back in 2004 Branson set himself the task of creating a reusable suborbital space plane he dubbed SpaceShipTwo, modeled after the suborbital plane that had won the Ansari X-Prize and intended to sell tickets so that private citizens would have the ability to go into space.

His flight yesterday completed that journey. The company he founded and is slowly selling off so that he is only a minority owner now has a vehicle that for a fee can take anyone up to heights ranging from 50 to 60 miles, well within the U.S. definition of space.

Nonetheless, if you rely on the media frenzy about this particular flight to inform you about the state of commercial space you end up having a very distorted picture of this new blossoming industry. Branson’s achievement, as great as it is, has come far too late. Had he done it a decade ago, as he had promised, he would have achieved something historic, proving what was then considered impossible, that private enterprise, using no government resources, could make space travel easy and common.

Now, however, he merely joins the many other private enterprises that are about to fly into space, with most doing it more frequently and with far greater skill and at a much grander scale than Virgin Galactic. His flight is no longer historic. It is merely one of many that is about to reshape space exploration forever.

Consider the upcoming schedule of already paid for commercial manned flights:

» Read more