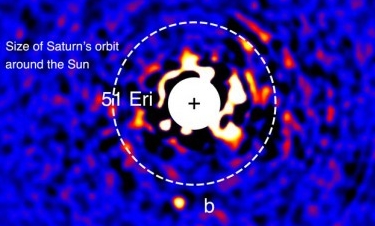

Astronomers find that Epsilon Eridani solar system resembles our own system

New data of the Epsilon Eridani solar system 10.5 light years away confirms that its debris disk has a structure somewhat resembling our own solar system.

The data has found that the debris disk has two narrow belts, one located at about the same distance from the star as our asteroid belt, and the other orbiting at about where Uranus is located. In addition, the system appears to have a Jupiter-sized planet orbiting the same distance from the star as does Jupiter.

New data of the Epsilon Eridani solar system 10.5 light years away confirms that its debris disk has a structure somewhat resembling our own solar system.

The data has found that the debris disk has two narrow belts, one located at about the same distance from the star as our asteroid belt, and the other orbiting at about where Uranus is located. In addition, the system appears to have a Jupiter-sized planet orbiting the same distance from the star as does Jupiter.