NASA’ safety panel illustrates the impossibility of exploration by NASA

Last week NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP) issued its 2017 report [pdf], detailing the areas it has concerns for human safety in all of NASA’s programs. Not surprisingly, the report raised big issues about SpaceX, suggesting its manned launch schedule was questionable and that there were great risks using the Falcon 9 rocket as presently designed.

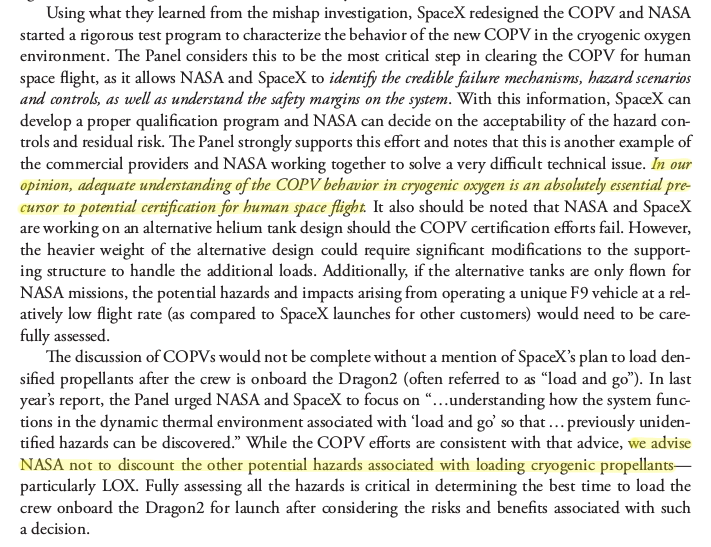

ASAP was especially concerned with the issues with the Falcon 9 COPV helium tanks and how they were connected with the September 2016 launchpad explosion, as well as SpaceX’s approach to fueling the rocket. Below is a screen capture of the report’s pertinent section on this.

The report complements NASA and SpaceX for looking at a new design for the COPV helium tanks, but also appears quite willing to force endless delays in order to make sure the issue here is completely understood, even though this is likely impossible for years more.

ASAP also raises once again its reservations about SpaceX’s method of fueling the Falcon 9, which would have them fill the tanks after the astronauts are on board so that the fuel can be kept cold and dense to maximize performance. This issue I find very silly. The present accepted approach is to fill the tanks, then board the astronauts. SpaceX wants to board the astronauts, then fill the tanks. Either way, the astronauts will be in a rocket with tons of volatile fuel and oxidizer. I really do not see why it makes that much of a difference, especially with SpaceX building a successful track record using its approach with each successful commercial launch. They did 18 last year alone.

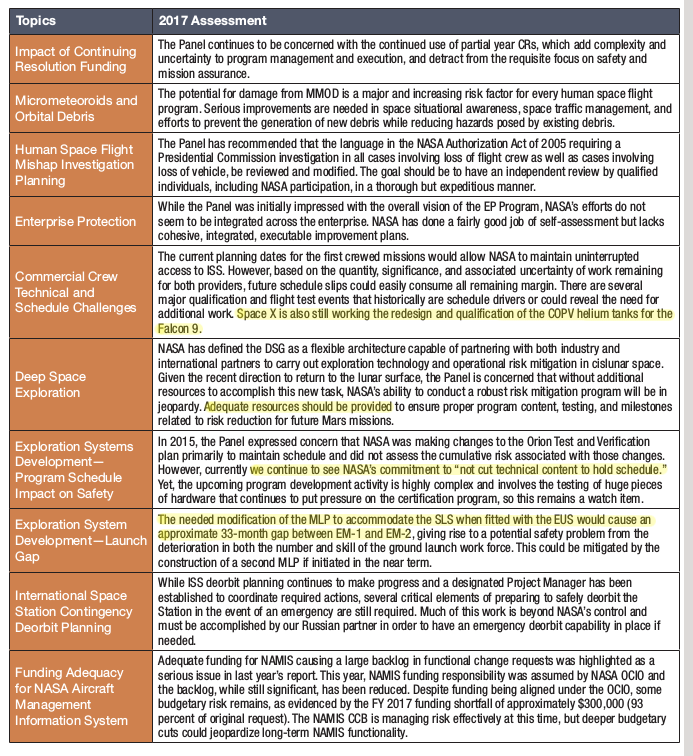

Below the fold is a screen capture of the report’s entire summary, with some sections highlighted by me.

This one-page summary reveals the absurdity of trying to do space exploration under NASA’s current bureaucratic framework. ASAP practically demands a risk-free space effort, and is quite willing to allow schedules to drag on forever to achieve this. NASA however is supposed to be in the business of exploration, which by definition means NASA is exploring the unknown, and cannot achieve a risk-free effort. In fact, the risks — and the failures — are exactly what NASA and the commercial companies require to learn and improve how they do things. If you try to eliminate them before you fly, you will never fly.

In discussing NASA’s deep space proposals, including its Deep Space Gateway idea of a Moon-orbiting space station, ASAP as usual sees only one problem: not enough money, which it couches in the phrase “Adequate resources should be provided.” This is the same argument that ASAP has been making for SLS and Orion now for more than a decade, resulting in those programs getting more than ten times the funds of commercial space, and yet, even now the report admits there are safety problems with both that might require further delays. For example, the cryptic sentence “The needed modification of the MLP to accommodate the SLS when fitted with the EUS” refers to the fact that — after NASA spent half a billion dollars re-configuring the mobile launcher (MLP) so that it can transport the first SLS rocket to the launchpad — the mobile launcher will need to be re-configured again for the second SLS launch because the second stage (EUS) will be different, resulting in a more than two year delay between the first and second SLS launches.

ASAP’s solution? “Adequate resources should be provided!” Build a new mobile launcher, at great cost, which would make the first launcher useless after only one use.

The report’s description of Orion is equally embarrassing, outlining how Orion’s first heat shield was a failure, and that there are even now questions about the new design.

Overall, the problem here is with ASAP itself. Imagine if we had had this kind of review in the 1800s:

The Government Safety Panel of Covered Wagon Design (GSPCWD) has found that Conestoga wagons do not have adequate safety protections against Indian attacks. The canvas walls cannot protect against arrows, and can burn too easily. Moreover, the wagon has too high a center of gravity, and can roll over too quickly. Before any settlers can move west using this vehicle it will have to be redesigned.

Exploration involves risks. If you want to explore, you accept those risks, while doing everything reasonable to address them, while moving forward quickly and practically. You do not try to eliminate all risks, only those that act to prevent you from moving forward. You then accept the tragic failures you couldn’t predict, fix what you can to prevent them from happening again, and quickly move on.

ASAP, and the philosophy that guides it, wants to eliminate all risks, even those that we can’t predict or might keep us from going at all. If we continue to allow this approach to remain in charge, the U.S. space program is never going to go anywhere.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

I’m listening to today’s House Committee hearing on NASA Commercial Crew Systems Development. The GAO representative said that while the current certification goal is Q1 2019 for both systems, “the program’s [NASA’s Commercial Crew Program office, I assume] own analysis” shows that certification is likely to slip to December 2019 for SpaceX and February 2020 for Boeing.

I’ve not heard dates that far out before.

Kirk: The goal of the big space powers in Washington, including many in NASA, is to slow commercial crew down enough so that SLS will look competitive with it. That is the heart of what is going on here.

The interests of the nation have long been forgotten in DC. Long forgotten.

Here is the GAO report / written testimony (released today) for the committee meeting which contains the December 2019 & February 2020 dates. It is a 23 page PDF. (I’ve not read it all yet.) https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/689448.pdf

Those dates are discussed on page 13, and don’t go much beyond what was said in the live testimony. It basically says that the program is in regular communication with the contractors regarding schedule, and that the program manager [Kathy Lueders] recognizes that both contractors use aggressive schedules to motivate their teams to which NASA adds additional margin, and that both contractors assume a greater efficiency factor than NASA does.

If NASA’s internal estimates are for certification in late 2019 / early 2020, then when will they start looking at purchasing another Soyuz flight?

Representative Don Beyer (D-VA) asked Hans Koenigsmann, “Can you give us an update on SpaceX’s timetable for manned spaceflight to Mars?”

Dr. Koenigsmann: “I don’t think I’m qualified for that. Obviously, that is a long-term goal that our founder and CEO, Mr. Musk, has. And there is a team working on this but it’s a … I want to say it’s a relative modest team and the main focus on the company is clearly on this particular program and getting to the Space Station. That is our first step into manned space travel.”

Rep. Beyer: “My colleague Mr. Perlmutter of Colorado has a seat on NASA’s 2033 flight to Mars.”

Rep. Perlmutter (from off camera): “I’ll go on SpaceX.”

Rep. Beyer: “If we can get rid of him earlier, that would be very helpful.”

Kirk: Having read the GAO report I can say that is is more of the same crap that ASAP is giving us. One of the delay issues is the amount of paperwork NASA needs to fill out to certify the private capsules. It appears NASA might actually cause delays because of this, and this alone.

The GAO does have one piece of good news. It states that NASA and SpaceX have agreed that if SpaceX does five launches safely using its fuel loading capabilities NASA will accept them. It seems to me that SpaceX has already done this, but I expect they will designate five specific launches, and have NASA people on hand to watch everything, just to make it official.

After much deliberation they’ve decided the only safe thing to do is never launch. Russia agrees to take the blame for any future loss of life at triple the current ticket price.

I wonder what the market for astronaut life insurance would be?

Robert wrote: “SpaceX wants to board the astronauts, then fill the tanks. Either way, the astronauts will be in a rocket with tons of volatile fuel and oxidizer.”

Isn’t it safer to have the astronauts on board, with the launch escape system, during fueling than to have the astronauts and closeout crew around a fueled rocket? Had the 2016 pad fire occurred with astronauts on a Dragon, the launch escape system would have taken them to safety, but could anyone working around the rocket have reached zip cords in time?

I think that the difference is between the Nedelin catastrophe, where many people working near the rocket died, and the Soyuz T-9 explosion, where the cosmonauts were whisked to safety by their launch escape system.

From the screen captured section of the report: “In our opinion, adequate understanding of the COPV behavior in cryogenic oxygen is an absolutely essential precursor to potential certification for human space flight.”

The question is, do they define when that understanding is adequate? Are the conditions stated just before adequate, and if so, why is the report using italics for that statement?

From the screen captured section of the report: “Additionally, if the alternative tanks are only flown for NASA missions, the potential hazards and impacts arising from operating a unique F9 vehicle at a relatively low flight rate (as compared to SpaceX launches for other customers) would need to be carefully assessed.”

Why should a low flight rate be a concern, and why are they not more concerned with SLS’s even lower flight rate? Low flight rate relative to what? Not relative to SLS.

The conclusion that this is political, to support the failing SLS, may be correct. Robert wrote: “If we continue to allow this approach to remain in charge, the U.S. space program is never going to go anywhere.”

I will take this opportunity to once again link to Bill Whittle’s analysis of the deal with reality. We have to take risks if we are to explore and learn how to do our engineering right:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXbdJ3kyVyU (7 minutes)

“You see, either you live for something, something worth dying for, or you just rot on the installment plan. That’s the deal.”

Last year, there were no fatalities worldwide in large jetliners. This took almost a century of commercial airline flights, and hundreds of fatal accidents, to learn how to do.

This does not mean that we take unnecessary risks, but to understand the risks and that some risks are necessary in order to discover what can go wrong. Analysis can get us only so far, we have to actually fly the thing to make sure it works.

NASA Never Allow Space Access

Edward: I came to say the same thing. Unfortunately I forget the source but my understanding was SpaceX want to board the astronauts before fueling so they are protected by the launch escape system. I’m not sure why NASA objects to this. If the rocket doesn’t explode – great! If the rocket does explode in an unexpected Amos 6 style, would you rather be in the capsule trusting your life to the LES, or climbing up the tower…?

In the end i know one thing.

All of these things NASA is damanding of Space-X and anyother private laucher are really only for NASA.

They have absolutly no control over the company or what it does except for what it does with NASA.

When Space-X and other private companies are tired of all this BS they will just launch all on their own. Without NASA’s permition or qualifications or cash.

SLS doesn’t have a chance in heck of getting past one launch, manned or unmanned. What private company is ever going to pay to use it? And what mission does NASA have planned and funded for it? Nothing.

As soon as NASA quits the space station its up for grabs. Any private company that wants to can send anyone they want to it. If NASA declairs they want to scrap it how will they stop a salvage operation? How can they stop the russians from salvaging it by just saying they are not leaving it?

The future of NASA is in deep space exploration not LEO. Low Earth Orbit is now the perview of those who want to exploit it, operate in it and make a profit in it.

We are literally one billion dollar investor away from having a space hotel. We have the launcher, the manufacturer, the experienced personel to assemple it and if the price is low emough about 5000 people world wide who could afford a month long stay and might be talked into it.

The international space station could then just be used for a cheap research station. the Russians wouold love to launch scientists up for a few million a trip.

Lockheed and Boeing can keep bribing NASA to set all these tests and goals as delaying tactics but in the end its over. The writing is on the wall. technology has given the small company the ability to compete with the big guys. And there is no new tech out there that the big guys have that sets them apart and above those small guys. those small guys are starting to offer everything the government needs and wants. And they are doing it far more affordibly.

I have a question.

Does NASA allow the progress freighter dock without the arm assist?

If so why not the dragon?

Bob -4 th paragraph, I think you have a “SpaceX” where you want a “NASA” – If I am reading this correctly.

The sentence is” SpaceX wants to board the astronauts then fill the tanks.” I think it is NASA that wants this to keep the O2 and fuel cold as long as possible. – the prior practice of SpaceX be damned.

In any case NASA and SpaceX are NOT interchangeable and the delay seems to be part of the plan. That said, I expect that there will be an accident in the path toward commercial manned space. The reaction by NASA, the press and the public as well as possibly Congress will be the test of if we have the nerves to continue our journey into manned space,

Marooned (1969)

https://youtu.be/yD1hbplN4DE?t=143

6:53

“When Space-X and other private companies are tired of all this BS they will just launch all on their own. Without NASA’s permition or qualifications or cash.”

I have been wondering about that. Can SpaceX launch something out of LC39A without NASA permission and/or agreement? Or launch from the Air Force complexes without Air Force agreement? I do not know.

They may say ok we will just remove ourselves from your influence and launch out of Bolsa Chica. My understanding is that each flight has to be licensed. What is to prevent someone at NASA talking to someone at the FAA (?) and make sure the license is refused?

And if SpaceX says screw it we are moving to Someplaceostan could not the previsions of ITAR be brought out in full force?

From what I have been seeing of late Government corruption is a powerful thing.

Just being pessimistic but this situation seems to the an existential threat to SpaceX; NASA/Boeing/the ‘bama boys look to be playing hardball to protect their own rice bowl. Of course Elon is a clever devil and may see the way to navigate around these obstacles.

Some years ago Elon was quoted as saying that if NASA would accept the same level of safety from Dragon 2 as they were willing to accept from Shuttle they could have launched last year (tongue in cheek here). Which brings to mind, can Soyuz meet the published safety concerns? I suspect not.

Chris: No, my sentence is correct, as far as I understand things. SpaceX wants to wait as long as possible to load the propellants because of how they fuel, which means they will be fueling with astronauts in the capsule.

Michael-

You need an FAA launch-license.

[https://www.faa.gov/data_research/commercial_space_data/licenses/]

“step out of line, the Man come, and take you away.”

https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ast/licenses_permits/

I can not find anything in the FAA permits that requires anything from NASA.

NASA required them to try to use the landing barge system until Space-x proved they could reliably hit their target and not fly off into a city someplace.

The FAA’s main requirements are public safety. Not pilot or craft safety.

I do not know but does Space-x really need the super cold fuel method or can they launch the manned dragon to the space station without it?

Space-X could just be pushing for this with hope knowing they don’t really need it for operation but could use it for better profit with heavier payloads.

I agree with Robert and Edward. There is a huge double standard between how ASAP treats commercial launch providers and NASA’s SLS. By their own metrics, SLS is far worse. Similarly, the proposed solution of more money for SLS would work just as well (that is, just as badly) for commercial launch. It’s obvious bias in favor of the SLS program.

As I see it, NASA has a massive conflict of interest between SLS and the entire US commercial launch industry and the future of the US in space. This is best resolved by ending SLS. We’ve gone past any need for NASA to design and fund its own launch vehicles. Further, the SLS is so underperforming in cost and launch frequency compared to the private world, it wouldn’t stand a chance, if there were an even playing field.

pzatchok wrote: “When Space-X and other private companies are tired of all this BS they will just launch all on their own. Without NASA’s permition or qualifications or cash.”

They will certainly want to do this, but they still have to get an FAA license to launch, and the FAA may be reluctant to authorize a launch of an uncertified manned craft.

pzatchok wrote: “SLS doesn’t have a chance in heck of getting past one launch, manned or unmanned. What private company is ever going to pay to use it? And what mission does NASA have planned and funded for it?”

Unfortunately, Congress has decreed that NASA will send a probe to Jupiter’s moon Europa on SLS, so there is one guaranteed mission for SLS. This probe could be launched on another rocket, but SLS would allow for going straight to Jupiter without a Venusian gravity assist. This saving of a year or two is expensive.

pzatchok wrote: “We are literally one billion dollar investor away from having a space hotel.”

Bigelow is that billion dollar investor. His plan is to launch his space habitat in 2020, but if NASA refuses to certify either company, his business takes a hit of a year or two in additional expenses.

NASA is looking at deorbitting the ISS rather than allowing commercial companies to use it. What a waste. Hopefully, they will extend its mission beyond 2024 to 2028 or even later. We paid a pretty penny for that most expensive thing ever built, and I want to get my moneys worth from it.

This topic reminds me of an essay in Space News. It pivots away from SpaceX but it fits in with the Capitalism In Space theme. It talks of a civil war between advocates of government-run manned space program and advocates of commercial manned space:

http://spacenews.com/op-ed-a-house-divided-or-in-this-case-a-rocket/

The essay explains the political nature of SLS (“The projects’ real purpose is to keep the space shuttle workforce employed in those states where NASA has a disproportionate economic impact.“) and how Constellation turned from the space exploration project that George W Bush had intended into SLS, a jobs program that helps keep incumbent congressmen in office.

The essay ends by suggesting that in order to eliminate SLS and replace it with something useful, we have to come up with something that satisfies Congress’s political and economic purposes for keeping it. In essence, we have to do as Milton Friedman said: make it politically profitable for the wrong people to do the right things.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEVI3bmN8TI (1 minute)

Although I agree with the overall essay, I have a couple of comments on it:

The essay says that because of this civil war “Resources are split” between government space and commercial space. This is clearly a reference to NASA’s budgets for SLS and the Commercial Crew Development program. However, SpaceX is learning how to self-finance innovations while providing lower priced service. Other companies are also setting themselves up to self-fund their own development of innovations and new services. Planet is one of these companies. XCOR was doing this, too, but lost an important customer and finally went out of business. Success is not guaranteed, but resources are being found in non-governmental areas.

The NASA budget choices are probably influenced by the “massive conflict of interest between SLS and the entire US commercial launch industry” that Karl Hallowell noted. Congress sets the budgets, but NASA probably has more of Congress’s ear than does the US commercial launch industry.

The essay says, “Even if the SLS ultimately flies, it is far too specialized and expensive to do much to expand the human economic sphere into the inner solar system.” This is why commercial space, not government space, will be first to get to Mars and to go back to the moon. Space is a great economic area, but governments do not see that as a virtue.

The author says “Two presidents in a row — Bush and Obama — have tried in varying degrees to redirect NASA away from the Apollo model, only to be blocked by institutions and senators who are answerable to local NASA employees.” The Senators are not answerable to local NASA employees but to the people of the local state, who see a great benefit to money flowing into the NASA center or contractor(s) in their state. There aren’t enough NASA employees to elect senators, but other voters are happy when a senator brings pork into their state. To solve this problem, we need those voters to feel the cost of that pork so that they stop wanting it.

What evidence does the panel present that the copv design and loading procedure is not adequately understood?

tomdperkins: None.

tomdperkins asked: “What evidence does the panel present that the copv design and loading procedure is not adequately understood?”

This may come under the heading of known unknowns. One problem was discovered in a (literally) spectacular way, so what other “previously unidentified hazards” have not been discovered? NASA and SpaceX may have focused on that one specific problem and not extended the testing to find other possible problems that have yet to show themselves. ASAP is not questioning the design and procedure so much as they are questioning the overall “COPV behavior in cryogenic oxygen.” They may be concerned about behavior during launch (e.g. vibration, stresses, helium tank pressure changes, and drainage of the tanks) or while on the pad (e.g. drainage after a launch scrub or LOX warming during an unexpected hold).

Although this is not part of tomdperkins’s question, the second paragraph in Robert’s first screen capture noted that the concern with loading the LOX after the astronauts are aboard come from the COPV problem. Thus, the unknowns have raised safety questions. As an advisory panel, they need to advise NASA of their concerns.

Their wording “absolutely essential precursor,” shows a great deal of concern. They are repeating their concern from last year’s report: “In last year’s report, the Panel urged NASA and SpaceX to focus on ‘…understanding how the system functions in the dynamic thermal environment associated with “load and go” so that…previously unidentified hazards can be discovered.’”

Engineers tend not to get emotional when expressing things in reports, so wording counts. It is the difference between the statement “Obviously a major malfunction,” from NASA’s Steve Nesbitt, and “Oh, the humanity!” from Herbert Morrison.

Anthony Colangelo at Main Engine Cutoff raises a devastating point about the double standard being meted out by NASA to SpaceX in its requirement of seven successful flights of the Block 5 Falcon 9 – not vis-a-vis SLS, but vis-a-vis Boeing and Atlas V.

“…This requirement grew out of concerns about SpaceX and how frequently they update the design of Falcon 9. And from where NASA stands, it’s a totally valid concern and requirement.

The problem is that it has very blatantly only ever been applied to SpaceX.

Starliner is flying on top of an Atlas V—a launch vehicle with a long, successful history. But flying crew on an Atlas V requires some changes to eliminate abort black zones—sections of flight where aborts are impossible. And doing that requires adding a second engine to Centaur, the upper stage of the Atlas V.

Dual Engine Centaur is not a new concept—Centaur flew with two engines for most of its history. But the last flight of a Dual Engine Centaur was on February 21, 2002–an Atlas IIIB launching Echostar 7. That launch was the first flight of Common Centaur, which is the version of Centaur flying today on Atlas V.

…Starliner’s first flight will be the first flight of the Dual Engine Common Centaur on Atlas V. Starliner’s second flight—its first with crew—will be flying the second.

Think about that.

Sorry I neglected to insert the link to the Colangelo piece in that last comment. Here it is:

https://mainenginecutoff.com/blog/2018/01/stable-configuration-double-standard

Richard M: Thank you. I am going to write an op-ed on this subject next week. This is good information for that piece.

I think that my response to tomdperkins needs a little more comment.

I wrote: “Their wording ‘absolutely essential precursor,’ shows a great deal of concern.” Since they are repeating this concern again in this year’s report, it is conceivable that neither NASA nor SpaceX are working on an “adequate understanding of the COPV behavior in cryogenic oxygen,” whatever “adequate” means to ASAP. It may be that NASA and SpaceX do not have the same concern as the ASAP.

I believe that SpaceX is sensitive to safety and reliability, because past accidents have cost them dearly in money, schedule, and reputation.

Elon Musk learned about the need for quality the hard way when, early in its existence, Tesla had to recall every car it had made, costing the company money and schedule that should have been used for developing its assembly line to make cars in large numbers.

The 2016 pad fire directly lost SpaceX two customers’s payloads that had already been on their manifest, for a loss of at least $100 million. Other potential customers may go — or may already have gone — to other launchers due to the reduced availability of timely launches from SpaceX for the next few years, further reducing revenues. Falcon Heavy has been delayed due to the need to use Pad 39A for Falcon 9 revenue launches — the lessons they are learning with Falcon Heavy on the pad this week could have been learned months ago. The cost of repairing Pad 40 is both financial and manpower, resources that could have gone toward developing additional capabilities sooner than they will be, and some capabilities and projects may be cancelled due to lack of resources.

The 2016 Pad 40 fire and the 2015 loss of CRS-7 likely contributed to the ASAP having less confidence in SpaceX having an “adequate understanding of the COPV behavior in cryogenic oxygen,” and these accidents may have contributed to the double standard noted by Richard M.

Speaking of double standard, the ASAP report spends four paragraphs (top of page 13, bottom of page 15, and all of page 16) and a sentence (page 14, just before section III B, regarding a Merlin Engine test mishap) mentioning SpaceX by name in discussing problems, but no problems by Boeing are singled out in the report. Concerns about Boeing do not seem to be unique but are common with SpaceX’s Dragon; Richard M’s link points to ULA’s Atlas V, not to anything on Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner.

There does not seem to be any concern about SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft that is not also expressed about Boeing’s spacecraft, as typified in section III B, “Probabilistic Risk Assessment for Loss-of-Crew.” Although, I noticed that an equivalent section was not included for the Orion or SLS in section II, “Exploration Systems Development,” it is only in the Commercial Crew Program section. Apparently, Orion and SLS do not need a similar risk assessment for loss of crew. After all, as the report says, “When developing new human space flight vehicles, the unique nature of these systems and limited test data results in large uncertainties in the PRA [Probabilistic Risk Assessment] numbers.” I guess NASA’s Orion design results in a less uncertain PRA than Boeing’s Starliner or than SpaceX’s Dragon.

For the Exploration System (Orion-SLS), the biggest concerns are the ground crew attrition rate (last paragraph, page 8) during the 33 month hiatus while the mobile launcher is rebuilt to accommodate the second EUS design and the European Service Module’s zero-fault-tolerant systems (bottom of page 10). Apparently there is not the same emphasis on understanding these systems as on understanding the COPV’s behavior with cryogenic oxygen.

For ISS, the biggest concern seems to be “While there have been no incidents to date which have risen to the level of a recordable mishap, many of the emergent failures have been successfully mitigated due in large part to the rigorous training and adaptability of the ISS crew, as well as the sound engineering, spares planning, and technical guidance from ground control personnel.” (page 18).

The footnote on page 11 directs us to an interesting web page regarding Appendix A, Significant Incidents and Close Calls in Human Spaceflight: https://spaceflight.nasa.gov/outreach/SignificantIncidents/index.html

Finally, the report’s introduction points out the uncertainties that are created by running the nation’s budget through continuing resolutions rather than through actual annual budgets. I have noticed that the previous administration’s lack of insistence on budgets (budgetary discipline) has carried over into the current administration, thus the same uncertainties continue. “The ASAP reiterates once again the need for constancy of purpose, as NASA is on the verge of realizing the results of years of work and extensive resource investment in these programs. … We continue to strongly caution that any wavering in commitment negatively impacts cost, schedule, performance, workforce morale, process discipline, and—most importantly—safety. Also, we continue to be concerned with the pressure induced by the lack of budget certainty due to the ongoing use of continuing resolutions (CRs). The budget uncertainties associated with partial year CRs adds complexity to program management and inefficiency to execution. This detracts from maintaining the requisite focus on safety and mission assurance.”

Added complexity and inefficiency. We are not getting all that we are paying for. No wonder SLS looks like a repeat of the Shuttle financial and operational fiasco.

Gerstenmaier answered the fueling question during the hearing. They considered loading crew and then fuel for shuttle. Couldn’t get comfortable with it. The current approach is to load the fuel, let it settle, and then load the crew. It’s a well proven system whose risks are understood over hundreds of human spaceflights.

NASA levels some strict requirements for a program that it’s paying for that will carry its astronauts into orbit and everyone freaks out. You all need to calm down. This is not impossible. It’s difficult. But, human spaceflight is supposed to be difficult. It’s many times more dangerous than flying a satellite. If a comsat ends up in the ocean, there’s no grieving families burying their loved ones. The risk lies not in the percentages of rockets that fail but in the value of the cargo.

D. Messier wrote: “NASA levels some strict requirements for a program that it’s paying for that will carry its astronauts into orbit and everyone freaks out.”

I think that the “freak out” is not so much due to requirements applying to the commercial program as much as that the same “strict” requirements do not also apply to the Orion-SLS.

If an Orion “ends up in the ocean,” there will still be grieving families burying their loved ones as if a Starliner or Dragon ends up in the ocean. Moreover, NASA will take much more blame for an Orion-SLS failure than for a commercial space failure, as NASA is far more involved with Orion-SLS. The consequences are greater, too, as NASA will have to stand down its Exploration System (Orion-SLS) while the accident is investigated and corrective actions taken, but the loss of one commercial crew vehicle leaves the other still in place to continue operations.

Yes, lives are placed at risk in a manned spacecraft, but they are also at risk when they are around fueled rockets (manned or unmanned). There have been four pad fires, that I can recall off the top of my head: the Nedelin catastrophe in 1960, Soyuz T-10a in 1983 (I misidentified it as Soyux T-9, last Wednesday), Brazil’s VLS-1 fire in 2003, and SpaceX’s Falcon 9 fire in 2016.

The Nedlin and Brazil fires occurred as people were working around the launch vehicles, and many people were killed in each accident. Falcon 9 occurred with no one around, and no one was hurt. Soyuz T-10a occurred as the cosmonauts were in the capsule awaiting launch, and as I noted Wednesday, the launch escape system saved their lives. Only the Soyuz was a manned mission.

Nedlin was caused by an inadvertent signal igniting the second stage, causing the liquid fueled first stage to explode, while people were working around the fueled rocket. Brazil happened because of an inadvertent ignition of a solid fuel first stage booster, while people were working around the rocket. Soyuz T-10a occurred 90 seconds prior to launch due to a premature activation of a propellant pump. Only the Falcon 9 accident was due to fueling operations.

More people have died trying to fly satellites than trying to fly humans.

This empirical evidence (observations over thousands of launch attempts, manned and unmanned) suggests that it is safer for ground crews to stay away from fueled rockets and safer for crews to be aboard a fueled rocket with a launch escape system. The Shuttle had no escape system, so any failure such as the four pad fire examples would have resulted in loss of crew and in loss of ground crew, had they been around the fueled Shuttle.

At the time that NASA was considering whether to load fuel first and then load crew, for the Shuttle, only the Nedlin catastrophe had occurred, limiting actual experience, but giving evidence that the eventual choice was incorrect. On the other hand, the Solid Rocket Boosters were always fueled, so maybe it made little difference for the Shuttle, as the Brazilian accident shows that even solid rockets can be inadvertently ignited.

So, the question comes back to: is it still possible for NASA to explore space or are they paralyzed by the risks involved?

Additional questions may include: how much risk is NASA willing to take to explore space, in this dangerous and risky business? Is NASA willing to allow commercial companies to take on some of the still-risky mundane activities by following the path that NASA created?

Manned exploration may be difficult and dangerous, but it is not impossible, although maybe it has become impossible for the US government (NASA). They abandoned Apollo after its second brush with losing a crew, and abandoned the Space Shuttle for the same reason. Has NASA become too risk averse to operate a manned space program?

As with aviation, it will take a lot of experience, good and bad, to learn how to do fly to, in, and from space safely, because spaceflight does not have to be dangerous. This is why I linked to Bill Whittle’s video “The Deal,” on Wednesday.

One of the biggest objections to fueling with the crew aboard came from an advisory committee chaired by Tom Stafford.

https://spacepolicyonline.com/news/stafford-committee-worries-about-spacex-plans-to-fuel-rocket-while-crew-aboard/

He wrote a letter to Gerstenmaier 8 months before the Falcon 9 blew up on the launch pad:

https://spacepolicyonline.com/news/stafford-letter-to-gerstenmaier-raised-two-spacex-commercial-crew-issues/

Stafford risked his life flying in space four times. He is not a guy who is paralyzed by fear and unwilling to take risks. He and the other members of the committee have serious concerns with SpaceX’s plans based on decades of established practice. They feel the burden should be on SpaceX to prove that changing that practice won’t create additional risks to the astronauts. That’s a reasonable position that NASA is also taking.

D. Messier,

You wrote: “Stafford risked his life flying in space four times. He is not a guy who is paralyzed by fear and unwilling to take risks.”

I think that Robert’s point in this post is that NASA, after losing three crews and almost losing a fourth, is beginning to behave as though it is paralyzed by fear and is now unwilling to take risks to explore the solar system.

You wrote: “They feel the burden should be on SpaceX to prove that changing that practice won’t create additional risks to the astronauts. That’s a reasonable position that NASA is also taking.”

That would be the correct position to take, if the original decision had proved to be the less risky option. My review of the only four pad fires that I can think of suggests that the decision was faulty.

From the Stafford letter, quoted in the second link: “There is a unanimous, and strong, feeling by the committee that scheduling the crew to be on board the Dragon spacecraft prior to loading oxidizer into the rocket is contrary to booster safety criteria that has been in place for over 50 years, both in this country and internationally. Historically, neither the crew nor any other personnel have ever been allowed in or near the booster during fueling. Only after the booster is fully fueled and stabilized are the few essential people allowed near it.”

The ISS Advisory Committee may be unanimous, but I believe that history has demonstrated that there is less danger during fueling operations than after fueling is complete. History has also demonstrated that the launch escape system will save the astronauts’ lives. Added to that is the absence of a closeout crew to worry about.

The experience of thousands of launches has shown that there is more risk of premature commands for rocket ignition than of accidents during fueling. The practice created half a century ago did not take this into account. Stafford failed to explain why the accepted process is safer than the proposed new process, just that it “has been in place for over 50 years“.

I invoke Grace Hopper, where she noted that “Humans are allergic to change. They love to say, ‘We’ve always done it this way.’ I try to fight that.”

I certainly don’t know why it has been done this way, all these decades, you may not, and apparently Stafford is unable to explain it, either. When we forget why we ‘have always done it this way,’ we have difficulty in knowing whether it needs to be changed.

I am an engineer. We engineers tend to think that change is bad, that if it ain’t broken then don’t fix it. We can accidentally introduce flaws, if we do not fully understand the current system. However, “broken” has many meanings, including economic efficiency. SpaceX is fixing an expensive method to get into space, and they may now be (intentionally or unintentionally) fixing a crew ingress process that is more hazardous than had been believed five decades ago — a process created with insufficient experience to determine the true hazards, and is now blindly followed because “we’ve always done it this way.” This five decade old way may be broken, but we just do not know it, yet.

After all, what are the current risks? We know more about them now than we did half a century ago.

Without knowing that answer to this question, how do we know whether we create additional risks to the astronauts or reduce risks to the closeout crew if we change the current practice?

We now have at least four incidents to help guide our choices about working around fueled and fueling rockets. We no longer have to make these choices without historical experience.

Perhaps it is time to review the way that it has always been done rather than having to prove that change won’t cause additional risks.

The basic gist of your answer is this: you’re more knowledgeable about these things than Stafford, the committee and anyone at NASA who are all paralyzed by fear. And you put greater weight on those four incidents that you cite than the hundreds of launches where the fuel was loaded first then the crew.

I think that sums it up pretty well. You’re absolutely, positively convinced of this and apparently the long dead Grace Murray Hopper and the alive and well Bill Whittle agree with you. Your position is as much ideological as it is based on facts. That makes it very difficult to have a discussion about.

Near perfect safety can be achieved by erecting rockets on the launch pad, and not fueling them. This will prevent all hazards involved with fueling, launch, flight, reentry, and landing. Problem solved.

D. Messier,

You wrote: “The basic gist of your answer is this: you’re more knowledgeable about these things than Stafford, the committee and anyone at NASA who are all paralyzed by fear.”

You apparently failed to understand my comment. I explained that you and I “certainly don’t know why it has been done this way, all these decades” and that “apparently Stafford is unable to explain it, either.” Where my greater knowledge might come from is unclear, but the statement allows for Stafford to know more even though he may not be able to explain it. Further, you have removed the context from this statement to make it seem that I was saying something other than I said. Did you do this intentionally, or did you fail to understand the argument?

The ASAP has not said that they looked into the issue, they only stated Stafford’s position, suggesting that it is their reason for their own opinion.

Finally, my statement referring to NASA’s behavior was about Robert’s point of the post. It is Robert who seems to think that NASA behaves so risk averse that it has become impossible for NASA to conduct manned exploration of the solar system.

“And you put greater weight on those four incidents that you cite than the hundreds of launches where the fuel was loaded first then the crew.”

The launches that had no incidents do not show any advantage to loading fuel first. Why put any weight on them? I pointed out the one incident that occurred during fueling and and the three that showed us that a fueled rocket is dangerous to be around. Those are relevant launch attempts to consider. Indeed, the sole incident on a manned launch was where the fuel was loaded first then the crew loaded.

However, if you only want to consider the manned launches, then we have to ignore the SpaceX fire of 2016, bringing us the (false) indication that it is only unsafe to have astronauts or closeout crews at the rocket when it is fueled, thus the conclusion would definitely be to load the crew, then the fuel.

“You’re absolutely, positively convinced of this and apparently the long dead Grace Murray Hopper and the alive and well Bill Whittle agree with you.”

Unless you told either of them, neither of them know — or knew, in the case of Hopper — that we are having this conversation. Why do you assume that I would think that they agree with me?

“Your position is as much ideological as it is based on facts.”

You will have to explain the ideology to me, because I do not understand what you mean.

My conclusion and position is that “Perhaps it is time to review the way that it has always been done.” How is that ideological? Or are you suggesting that engineering practices are ideological? No, that can’t be it, because I proposed breaking from the “change is bad” engineering philosophy to suggest revisiting the reason for doing it the same way as half a century ago. Perhaps you are thinking that using additional, more recent, data as being ideological.

Considering that your position, now, is not to consider the facts but to belittle them and to belittle me, I think that you are having difficulty discussing this issue because you have run out of facts. It has become difficult for me to have a discussion, because you have abandoned the facts and instead misinterpret the comment then attack the misinterpretation. I believe that this is the classic knocking down of straw men type of argument, on your part.

The closest that I have read for why the crew should be loaded after fueling is that “The current approach is to load the fuel, let it settle, and then load the crew.” http://behindtheblack.com/behind-the-black/essays-and-commentaries/nasa-safety-panel-illustrates-the-impossibility-of-exploration-by-nasa/#comment-1037650 This suggests that there is a belief that agitated fuel has a higher risk of ignition than still or settled fuel. However, none of the pad fires has been due to unsettled fuel.