Terraces within one of Mars’ giant enclosed chasms

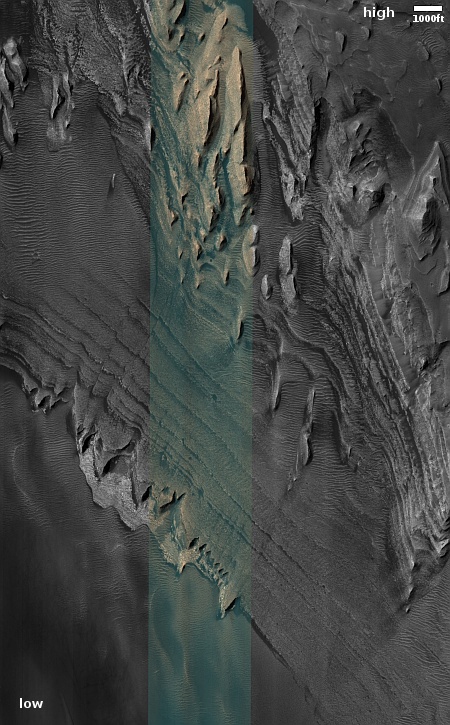

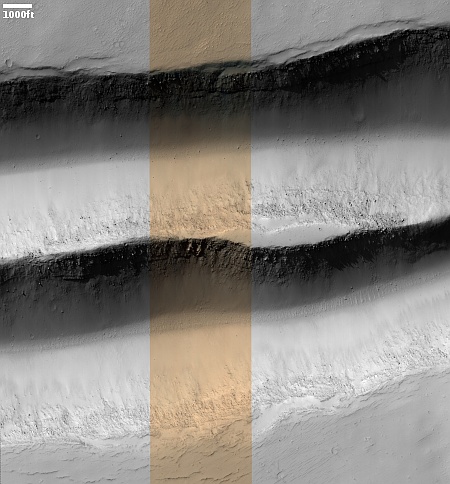

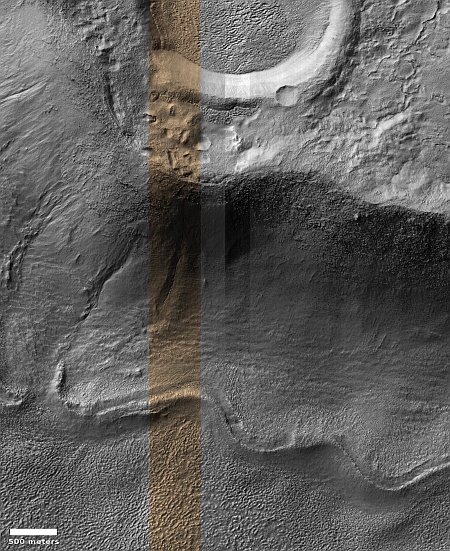

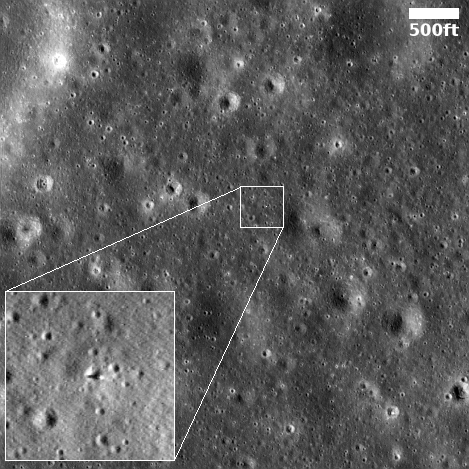

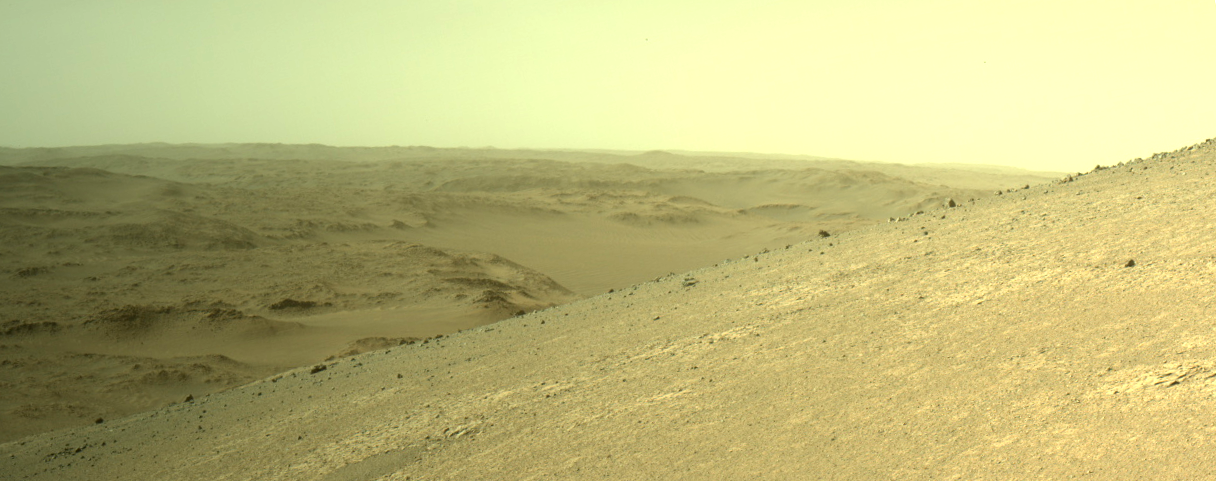

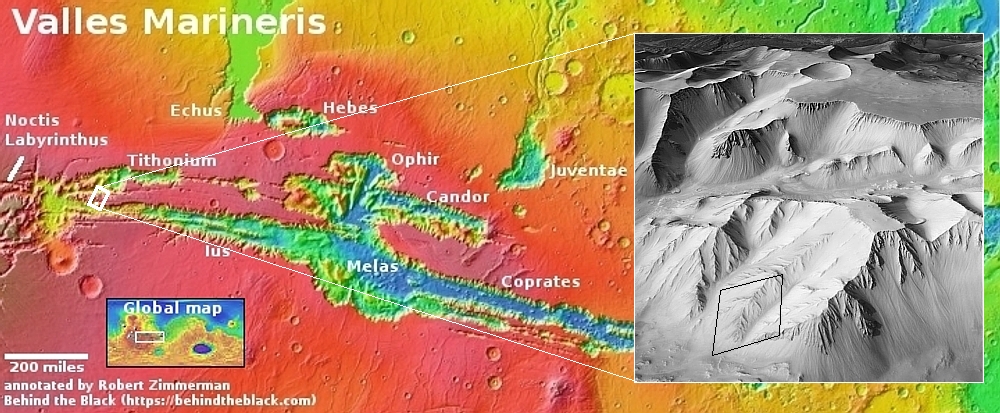

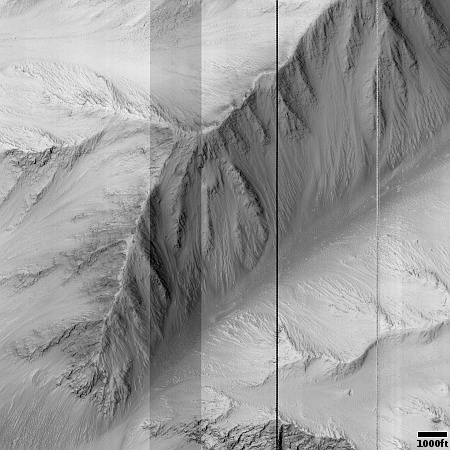

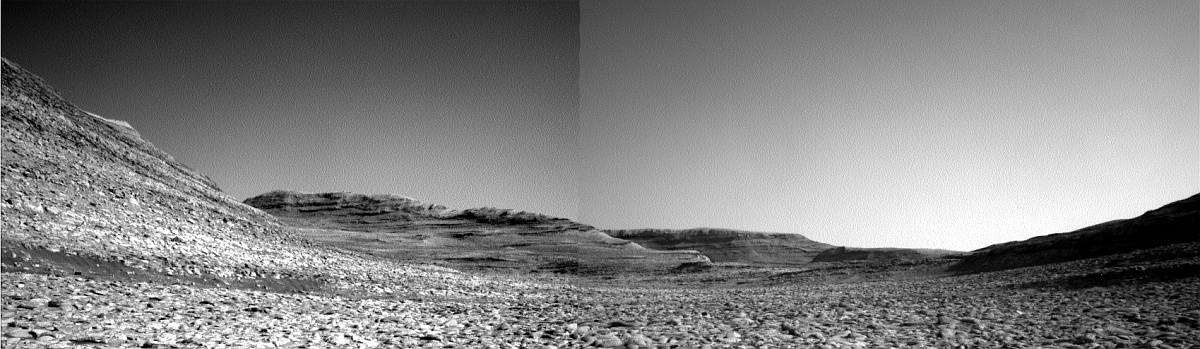

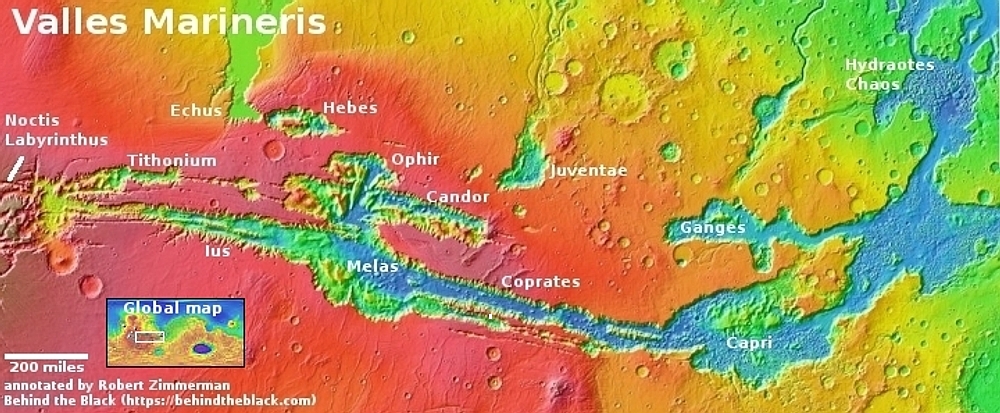

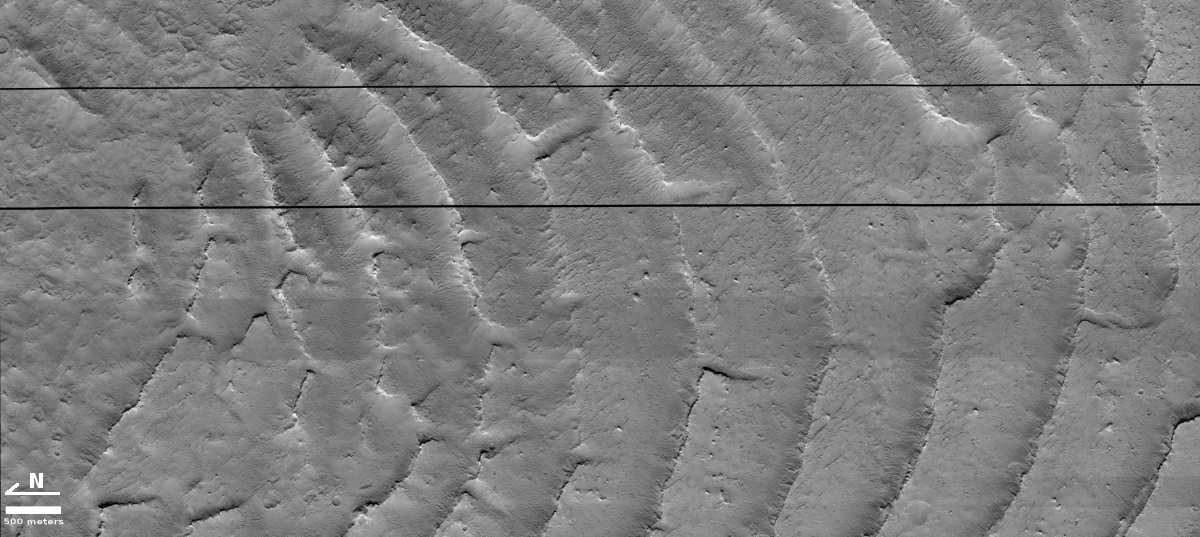

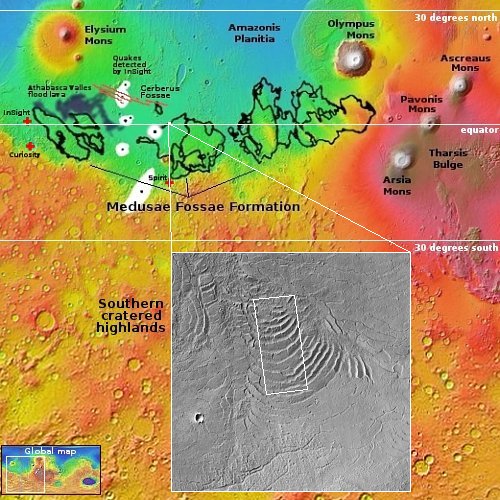

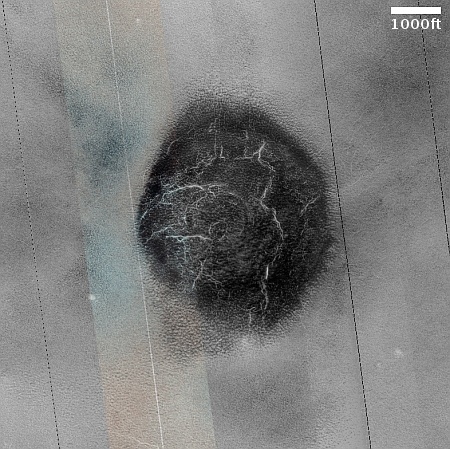

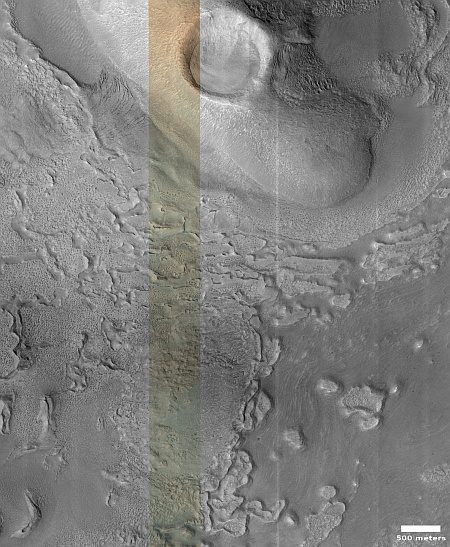

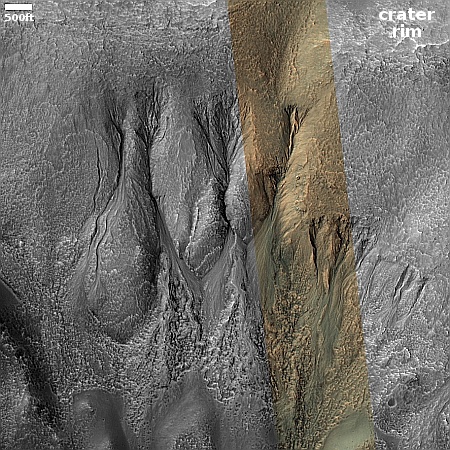

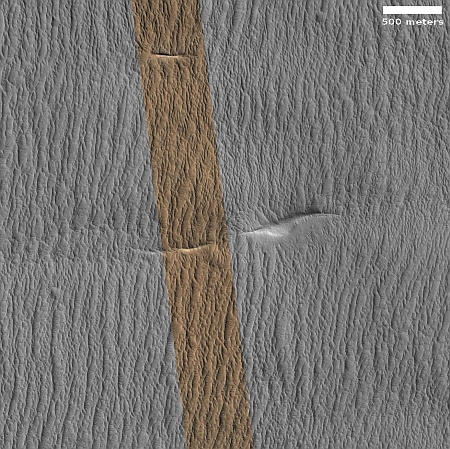

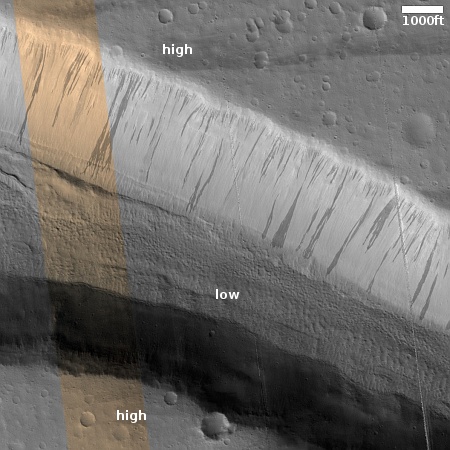

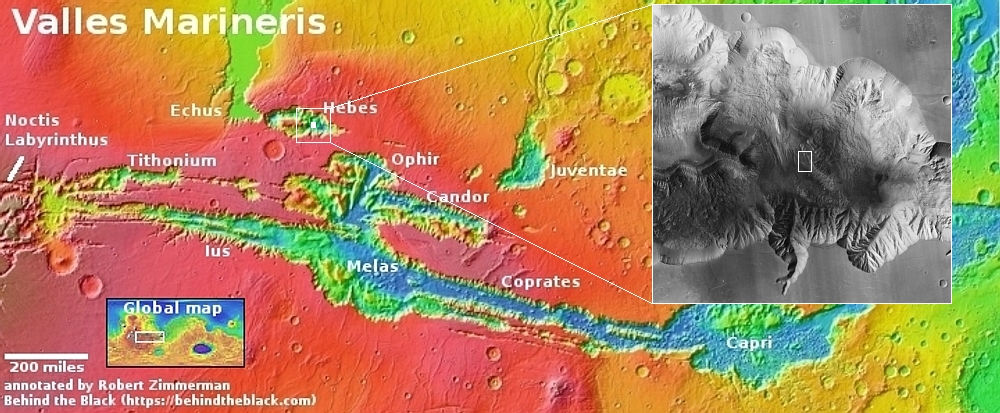

Cool image time! The picture to the right, rotated, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was taken on January 27, 2025 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). It shows the terraced layers descending down a 7,000-foot-high ridgeline within Hebes Chasma, one of several enclosed chasms that are found to the north of Mars’s largest canyon system, Valles Marineris.

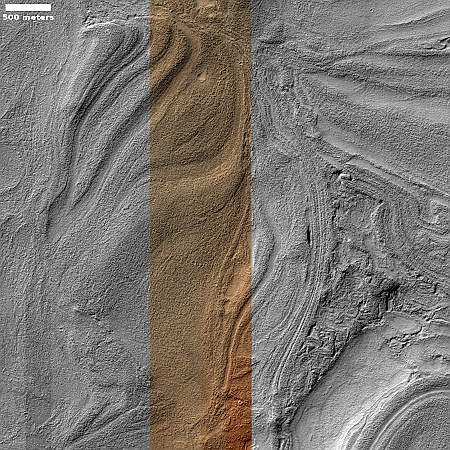

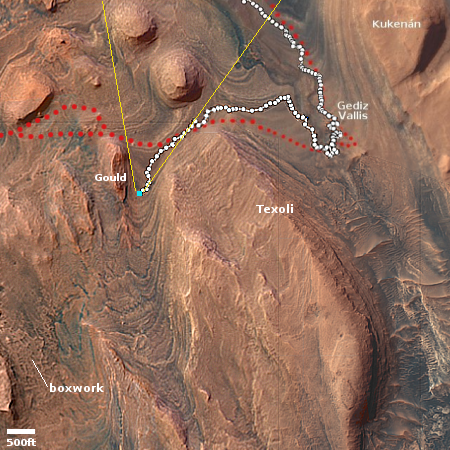

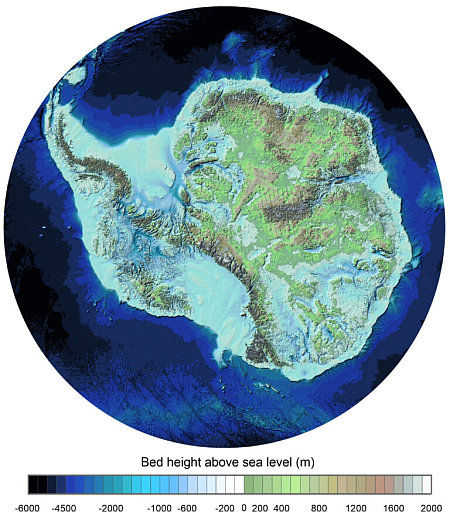

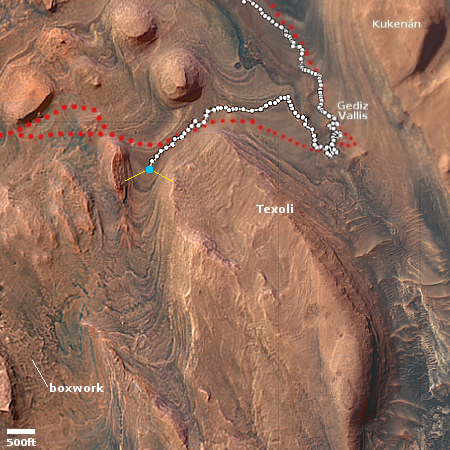

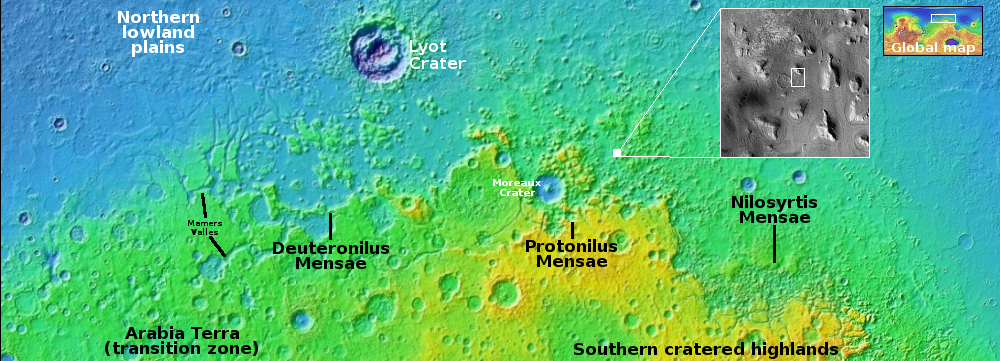

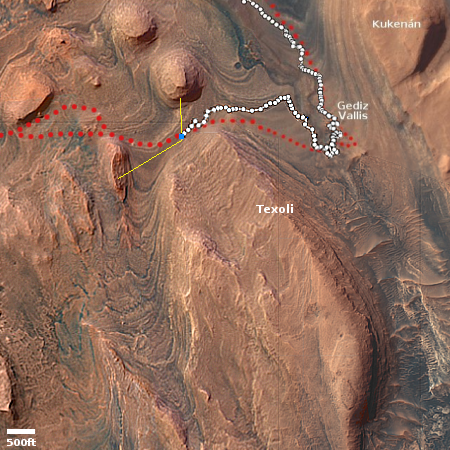

The white dot on the overview map above marks this location, inside Hebes. The rectangle in the inset indicates the area covered by the picture, which only covers the lower 5,000 feet of this ridge’s southern flank.

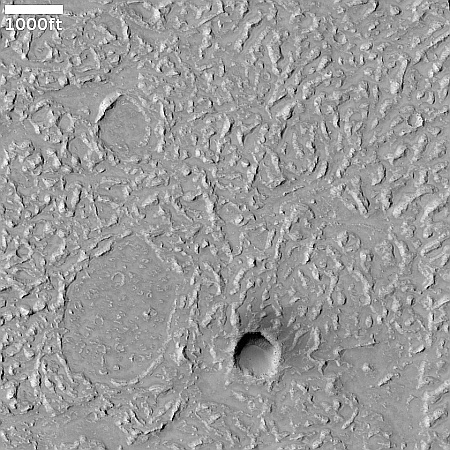

The ridgeline might be 7,000 feet high and sixteen miles long, but it is dwarfed by the scale of the chasm within which it sits. From the rim to the floor of Hebes is a 23,000 foot drop, comparable to the general heights of the Himalaya Mountains. Furthermore, this ridge is not the highest peak within Hebes. To the west is the much larger mesa dubbed Hebes Mensa, 11,000 feet high and 55 miles long.

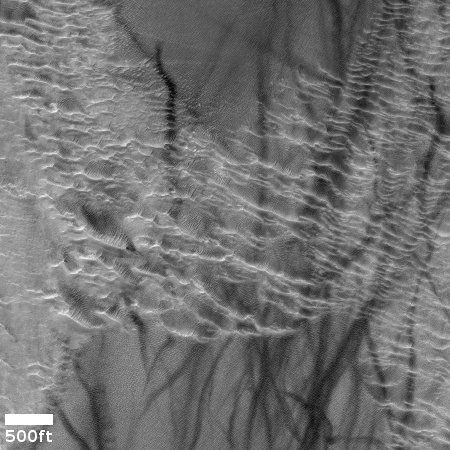

The terraces indicate the cyclical and complex geological history of Mars. Each probably represents a major volcanic eruption, laying down a new bed of flood lava. With time, something caused Hebes Chasm to get excavated, exposing this ridge and these layers.

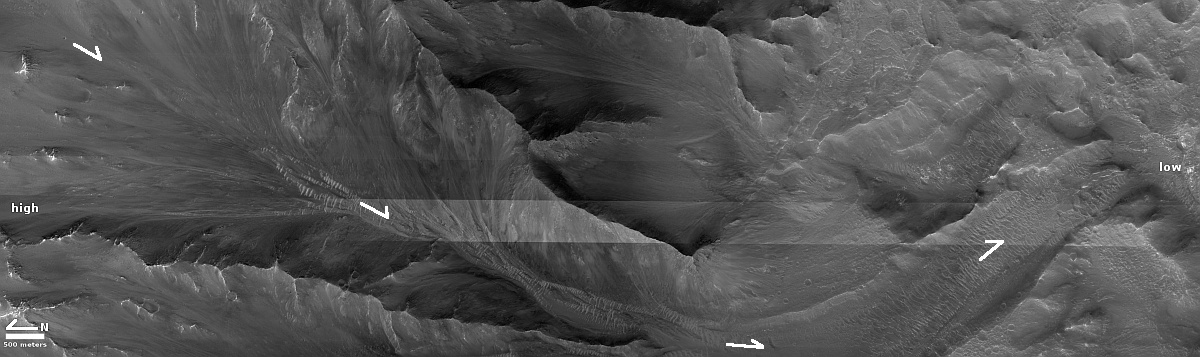

The excavation process itself remains unclear. Some scientists think the entire Valles Marineris canyon was created by catastrophic floods of liquid water. Others posit the possibility of underground ice aquifers that sublimated away, causing the surface to sink, eroded further by wind. Neither theory is proven, though the former is generally favored by scientists.

Cool image time! The picture to the right, rotated, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was taken on January 27, 2025 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). It shows the terraced layers descending down a 7,000-foot-high ridgeline within Hebes Chasma, one of several enclosed chasms that are found to the north of Mars’s largest canyon system, Valles Marineris.

The white dot on the overview map above marks this location, inside Hebes. The rectangle in the inset indicates the area covered by the picture, which only covers the lower 5,000 feet of this ridge’s southern flank.

The ridgeline might be 7,000 feet high and sixteen miles long, but it is dwarfed by the scale of the chasm within which it sits. From the rim to the floor of Hebes is a 23,000 foot drop, comparable to the general heights of the Himalaya Mountains. Furthermore, this ridge is not the highest peak within Hebes. To the west is the much larger mesa dubbed Hebes Mensa, 11,000 feet high and 55 miles long.

The terraces indicate the cyclical and complex geological history of Mars. Each probably represents a major volcanic eruption, laying down a new bed of flood lava. With time, something caused Hebes Chasm to get excavated, exposing this ridge and these layers.

The excavation process itself remains unclear. Some scientists think the entire Valles Marineris canyon was created by catastrophic floods of liquid water. Others posit the possibility of underground ice aquifers that sublimated away, causing the surface to sink, eroded further by wind. Neither theory is proven, though the former is generally favored by scientists.