Perseverance looks at Jezero Crater in high resolution

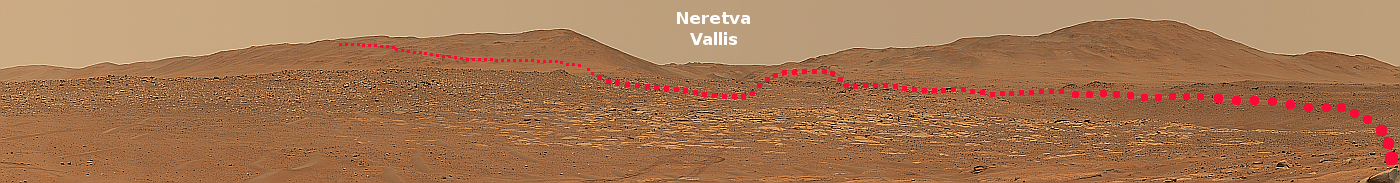

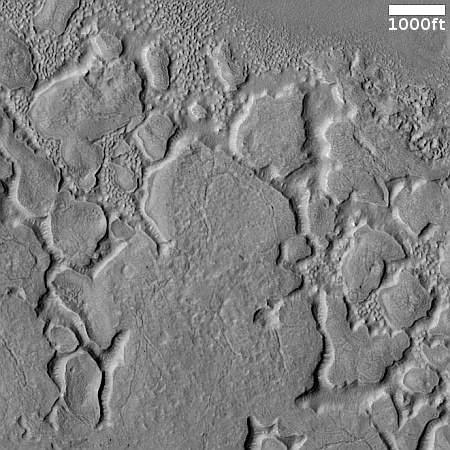

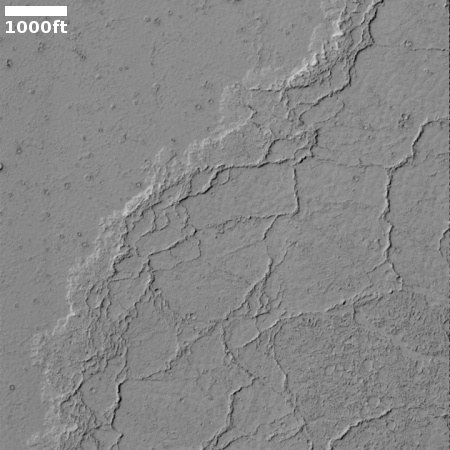

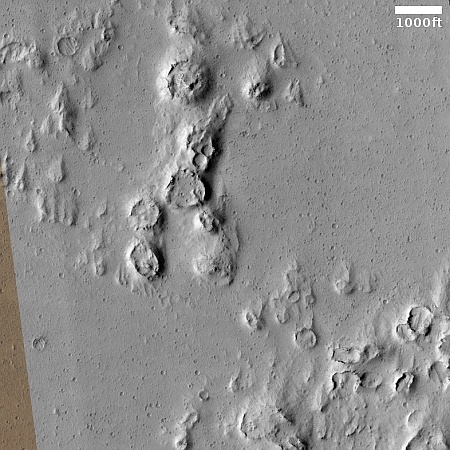

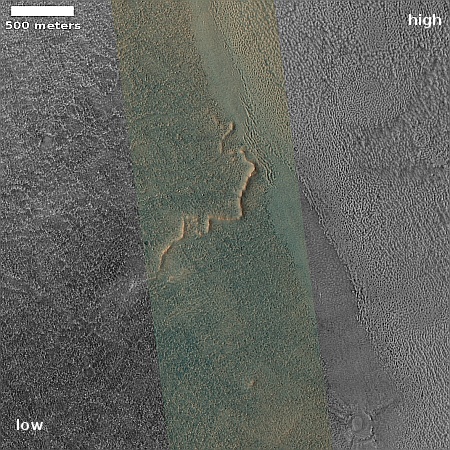

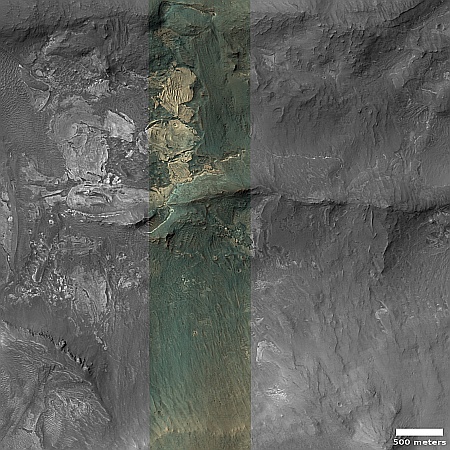

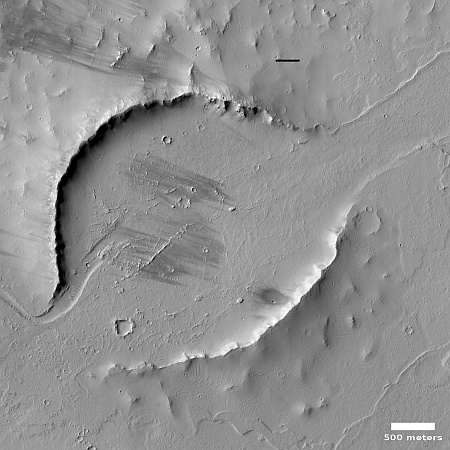

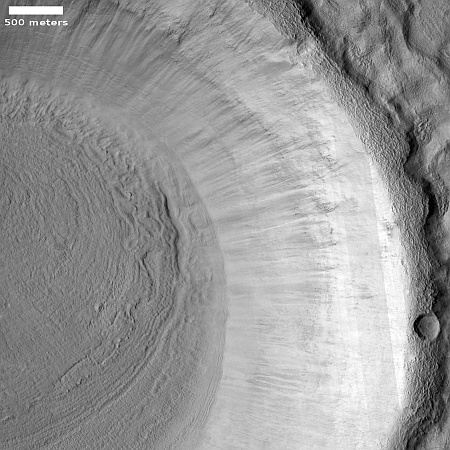

The Perseverance science team earlier this week released a mosaic taken by the rover’s high resolution over three days in November, showing the entire 360 degree view of Jezero Crater from where Perservance sat during the month long solar conjunction that month, when communications with Mars was cut off due to the Sun being in the way.

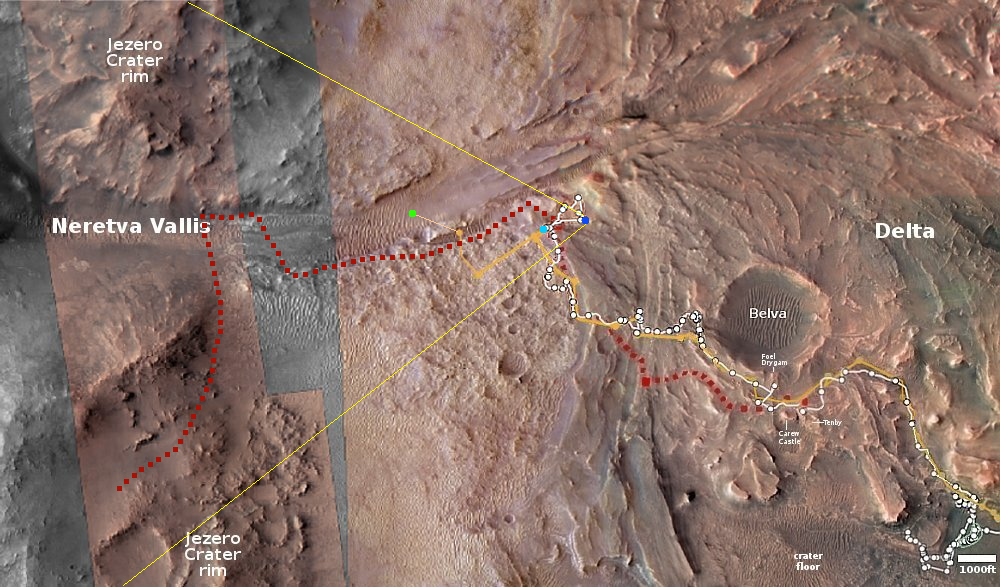

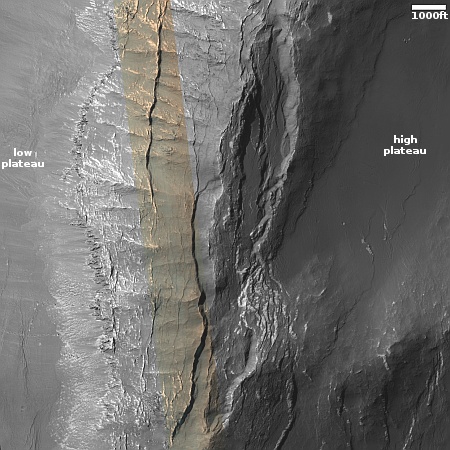

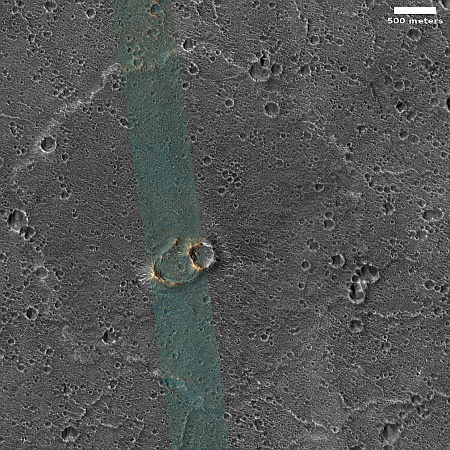

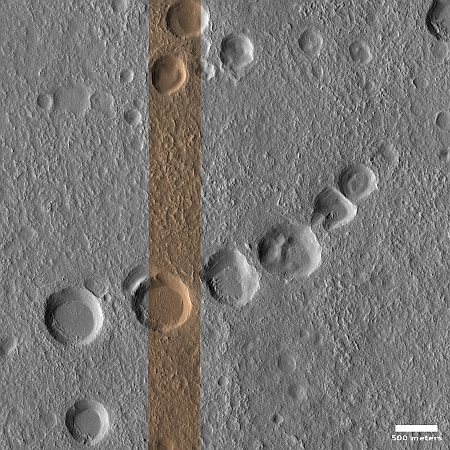

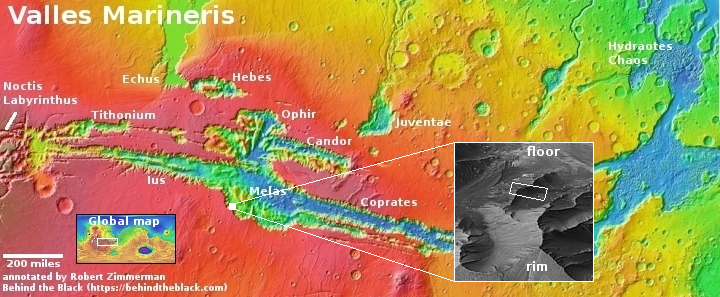

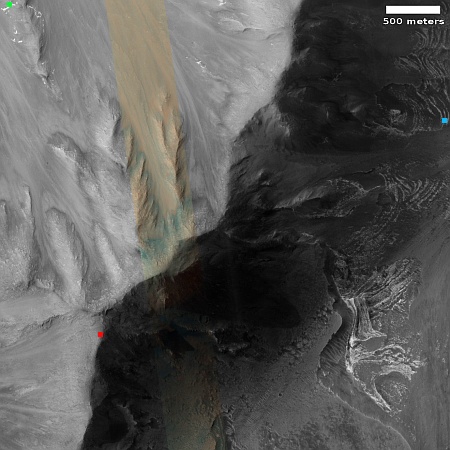

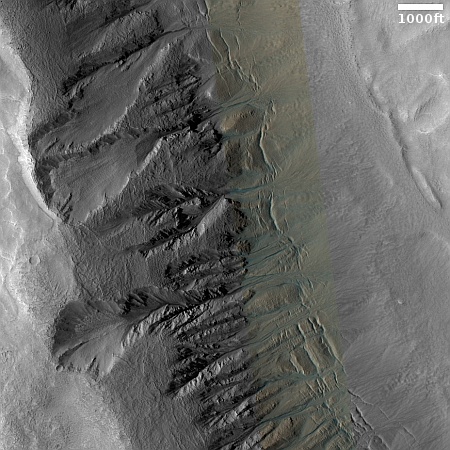

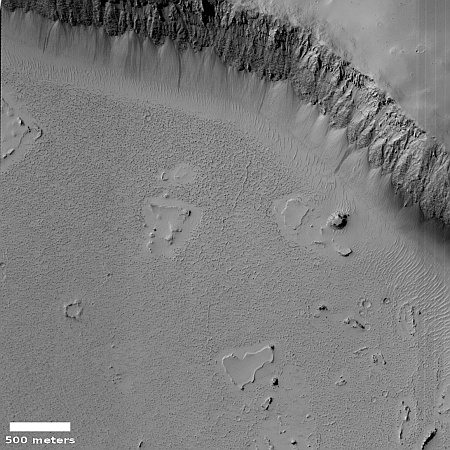

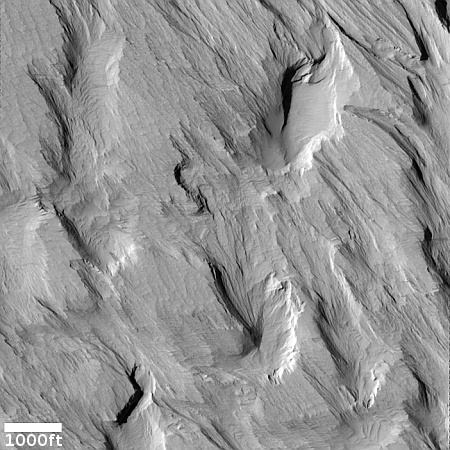

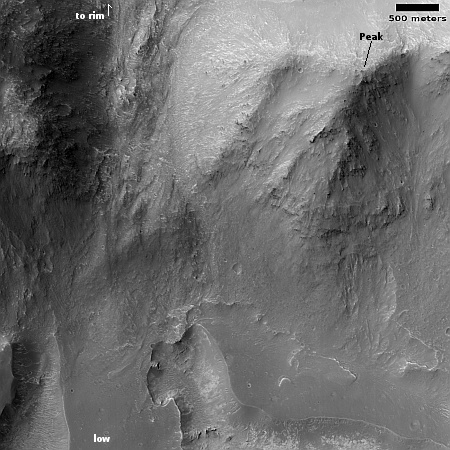

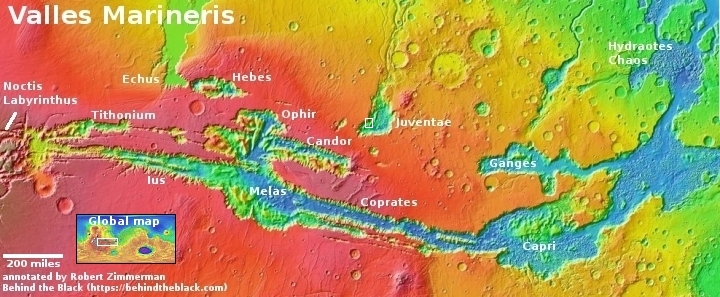

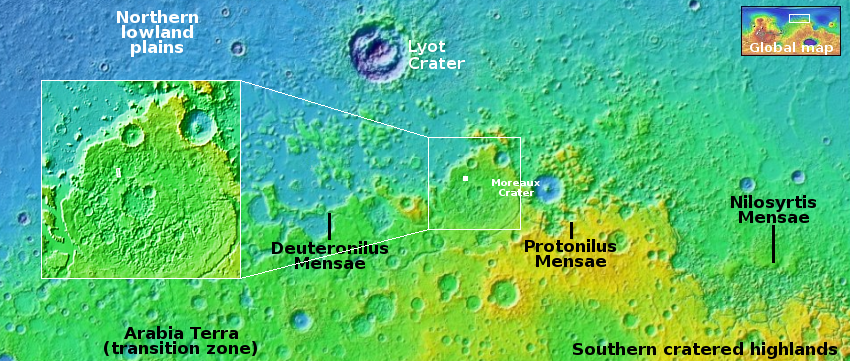

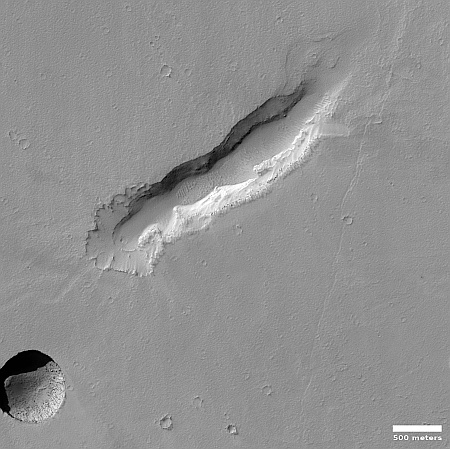

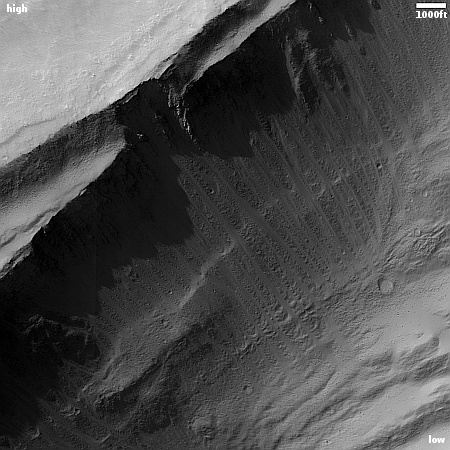

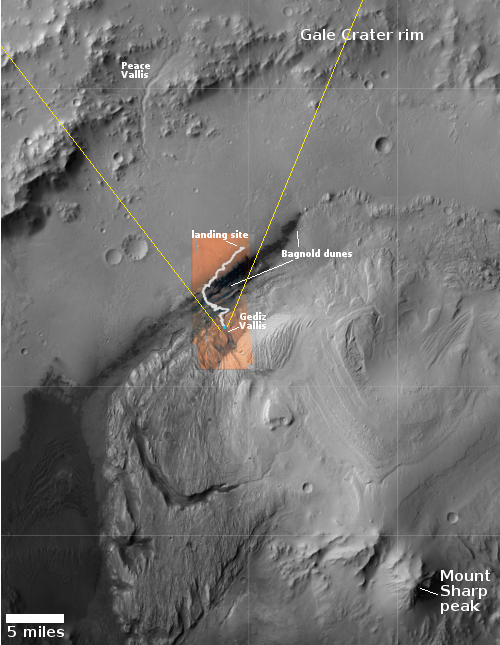

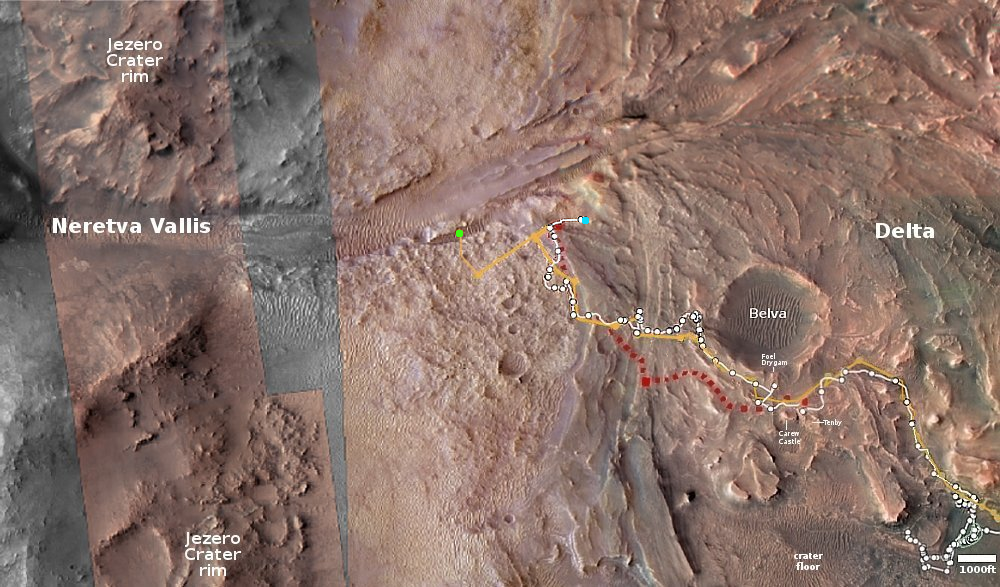

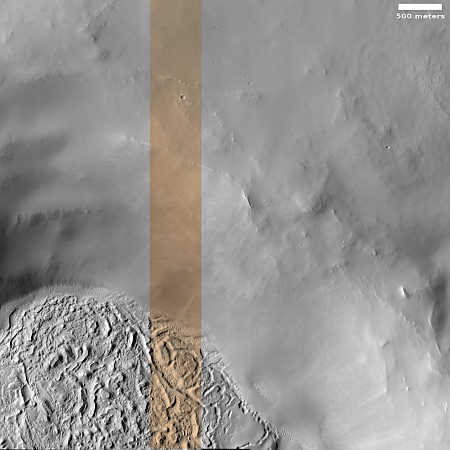

Part of that panorama, significantly reduced, cropped, and enhanced, is posted above, focusing on the western rim of Jezero Crater and the route that Perseverance will likely take in the future. Below is an overview map that indicates by the yellow lines the approximate area covered by this picture. The light blue dot marks Perseverance’s present location, while the dark blue dot marks where it took the mosaic and was also stationed during that solar conjunction. The dotted red line on both images marks the approximate proposed route that the science team is considering for leaving Jezero crater. Instead of going out through Neretva Vallis, they are instead considering heading south to go over the crater’s rim itself.

Ingenuity’s present position is marked by the green dot. This is where it landed after flight 67 on December 2nd. On December 8th the helicopter’s engineering team had released the flight plan for flight 68, scheduling it for December 9th, but as of this date it appears that flight has not occurred. I suspect the delay is because communication between Ingenuity and Perseverance is presently spotty, though the Ingenuity team has released no information.

The Perseverance science team earlier this week released a mosaic taken by the rover’s high resolution over three days in November, showing the entire 360 degree view of Jezero Crater from where Perservance sat during the month long solar conjunction that month, when communications with Mars was cut off due to the Sun being in the way.

Part of that panorama, significantly reduced, cropped, and enhanced, is posted above, focusing on the western rim of Jezero Crater and the route that Perseverance will likely take in the future. Below is an overview map that indicates by the yellow lines the approximate area covered by this picture. The light blue dot marks Perseverance’s present location, while the dark blue dot marks where it took the mosaic and was also stationed during that solar conjunction. The dotted red line on both images marks the approximate proposed route that the science team is considering for leaving Jezero crater. Instead of going out through Neretva Vallis, they are instead considering heading south to go over the crater’s rim itself.

Ingenuity’s present position is marked by the green dot. This is where it landed after flight 67 on December 2nd. On December 8th the helicopter’s engineering team had released the flight plan for flight 68, scheduling it for December 9th, but as of this date it appears that flight has not occurred. I suspect the delay is because communication between Ingenuity and Perseverance is presently spotty, though the Ingenuity team has released no information.